There is widespread concern today that many jobs will be lost to new computer technologies, as more human tasks can be performed by machines. A host of recent papers estimate that these technologies put anywhere from 9% of jobs to 47% at risk of automation in the near future (e.g. Arntz et al. 2017, Frey and Osborne 2017). Some people fear that this expansion in the range of automatable tasks is leading to mass unemployment and will require new policies such as a universal basic income (Ford 2015).

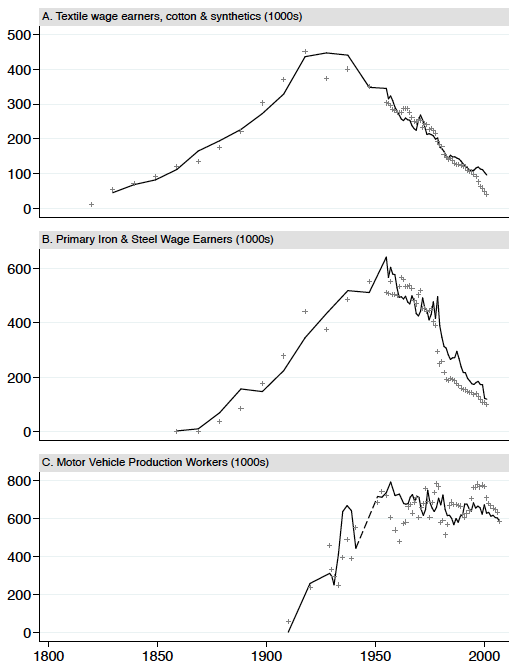

But those fears are misplaced. History shows that automation can and does often lead to growing employment in the affected industries. When major industries automate, their employment often rises rather than falls (see Figure 1). In the US, jobs in the cotton textile and primary steel industries grew rapidly alongside rapid automation for a century or more. Only later were sharp job losses associated with ongoing automation observed.

Figure 1 Production employment in three industries

Automation in the past clearly did not necessarily lead to mass unemployment. But are these historical examples relevant to today’s technologies? The key question is why automation was sometimes accompanied by job growth and sometimes not. In Bessen (forthcoming), I show that the changing employment response stemmed from a changing elasticity of demand. Different industries today are likely to have different demand elasticities and hence different employment responses to automation. Thus, while automation may eliminate jobs in some industries, it creates jobs in others. But this is not all good news. It means that many workers must adapt to new industries, skills, and occupations. The real policy challenge posed by new labour-saving technology is not mass unemployment but, instead, helping workers make these transitions.

The puzzle of automation and job growth

Why is automation associated with job growth in some industries at some times, yet with job declines in other industries at other times? Economists have tended to focus on the rate of productivity growth to understand the impact of technology on jobs. However, these explanations seem incomplete. For instance, Baumol (1967) argued that faster productivity growth in manufacturing relative to other sectors has led to a declining share of employment in manufacturing. Yet, manufacturing employment rose during the 19th century even though manufacturing productivity grew faster than other sectors, including agriculture. Similarly, Acemoglu and Restrepo (2018) argue that labour demand will increase with rapid productivity growth but will fall when productivity growth is only so-so. Yet, the textile and steel industries had similar rates of productivity growth both when employment was rising during the 19th century and also when employment was falling during the late 20th century.

A key explanatory factor is the changing nature of demand. Automation can, of course, increase demand. In a competitive market, reducing the amount of labour needed to produce a unit of output will reduce the price. If demand is sufficiently elastic, demand will increase rapidly enough so that employment will go up even if the amount of labour per unit declines. This is precisely what happened during the early years of the US cotton textile, steel, and automobile industries.

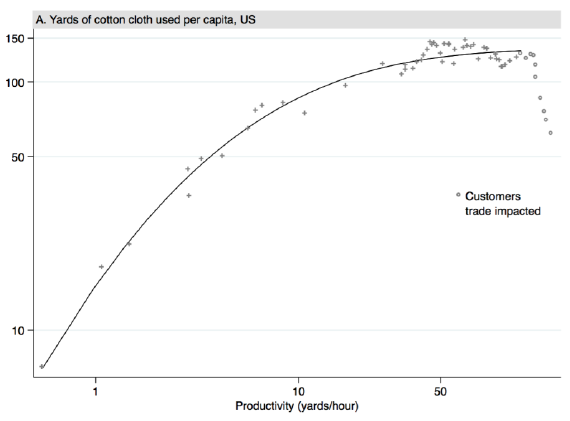

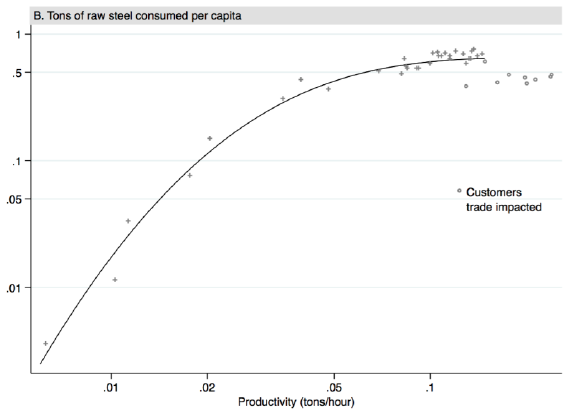

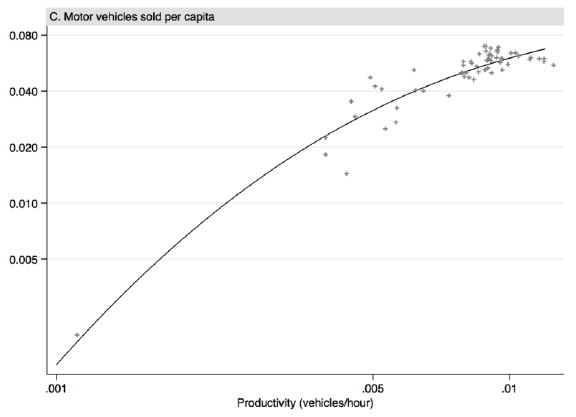

Figure 2 shows per capita consumption of these three goods by labour productivity, both plotted on log scales. Over the time period shown, labour productivity grew at a more or less steady rate for each of the three goods. But the demand response was quite different. During the early years, demand grew rapidly with productivity improvements, thus increasing employment. Later, demand growth slowed so that it no longer offset the decline in employment caused by the labour-saving effect of automation. Demand was highly elastic with respect to productivity during the early years and became highly inelastic later. The figure does not completely describe all that changed. For instance, it does not account for concurrent changes in income that might affect demand. In my paper, I do a more complete econometric analysis and find the same decline in the elasticity of demand with respect to labour productivity.

Figure 2 Consumption per capita

Demand satiation

We can understand this industry life cycle as a matter of demand satiation. During the early 19th century, the average adult had only one set of clothing. Cloth was expensive, much of it was made at home, on the farm, in a very time-consuming process. Automation brought price drops that tapped into large pent-up demand. People rapidly demanded greater quantities of cloth for additional clothing. But by the mid-20th century, most people had full closets and they used textiles in draperies, upholstery, etc. Automation continued to reduce prices, but those price drops no longer elicited such large increases in demand.

The changing elasticity of demand accounts for the inverted U shapes seen in employment in Figure 1. Highly elastic demand during the early years meant that demand growth more than offset the labour-saving effect of automation, leading to growing employment. Later, inelastic demand meant that the labour-saving effect dominated, and employment fell.

But how general is this industry life cycle pattern? To explore this question, the paper presents a simple model to explain these changes in demand. Building on the original notion of a demand curve by Dupuit (1844), the various uses of a commodity (cloth used for a first set of clothing, cloth used for upholstered furniture, etc.) creates a distribution function when ranked in order of relative value. At high prices, consumers will only choose the most valuable uses, that is, the upper tail of the distribution. The consumer’s demand is represented by the area in this upper tail. As prices decline, a larger portion of the distribution falls into the upper tail corresponding to increasing demand.

Figure 3 Consumption distribution function

I show that, for common distribution functions (normal, lognormal, exponential or uniform), demand will give rise to the inverted-U pattern in employment. That is, at sufficiently high prices, demand will be elastic (greater than 1), and as prices decline, the elasticity of demand falls, eventually becoming inelastic (less than 1). Applying this model, I find that the lognormal distribution function fits the data for textiles, steel, and automotive industries quite closely. We can also expect many of today’s industries to share this common property.

Implications for policy

The implication is that some industries today – those with substantial unmet demand – will respond elastically to automation, and are likely to see rising employment. Moreover, this is true even if new technologies bring automation at a more rapid pace. While the rate of productivity growth influences the pace of change, the elasticity of demand determines the sign of the change.

Of course, the elasticity of the response to automation is an empirical question. Recent studies indeed find evidence of positive employment responses in some industries with new information technologies, automation, and robotics. For example, Gaggl and Wright (2014), Mann and Püttmann (2017), and Bessen and Righi (2019) find that information technology appears to increase employment in many industries but decrease it in others. Koch et al. (2019) find that firms adopting robots increase employment, whereas Graetz and Michaels (2018) and Dauth et al. (2017) find no effect on employment. Acemoglu and Restrepo (2017), in contrast, find a negative effect.

These disparate findings suggest that the main impact of automation in the near future may be to cause a major reallocation of jobs, even if it does not permanently eliminate large numbers of jobs. This kind of change can be highly disruptive nevertheless. Workers switching industries often need new skills, and they may need to move to new occupations and sometimes new geographical locations. These transitions may cause periods of unemployment, and this poses a major challenge for policy.

To read original report, click here

References

Acemoglu, D and P Restrepo (2017), “Robots and jobs: Evidence from US labor markets”, NBER working paper no. 23285.

Acemoglu, D and P Restrepo (2018), “Artificial intelligence, automation and work”, NBER working paper no. 24196.

Arntz, M, T Gregory and U Zierahn (2017), “Revisiting the risk of automation”, Economics Letters159: 157-160.

Baumol, W J (1967), “Macroeconomics of unbalanced growth: the anatomy of urban crisis”, American Economic Review 57(3): 415-426.

Bessen, J E (forthcoming), “Automation and jobs: When technology boosts employment”, Economic Policy.

Bessen, J E and C Righi (2019), “Shocking technology: What happens when firms make large IT investments?”, Boston University School of Law, Law and Economics Research Paper 19-6.

Dauth, W, S Findeisen, J Südekum and N Woessner (2017), “German robots – The impact of industrial robots on workers”, IAB discussion paper 30/2017.

Dupuit, J (1844), “De la mesure de l’utilité des travaux publics”, Annales des ponts et chaussées 8(2): 332-75.

Ford, M (2015), Rise of the robots: Technology and the threat of a jobless future, New York: Basic Books.

Frey, C B and M A Osborne (2017), “The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation?”, Technological forecasting and social change 114(C): 254-280.

Gaggl, P and G C Wright (2014), “A short-run view of what computers do: Evidence from a UK tax incentive”, Working paper.

Graetz, G and G Michaels (2018), “Robots at work”, Review of Economics and Statistics 100(5): 753-768.

Koch, M, I Manuylov and M Smolka (2019) “Robots and firms”, Working paper.

Mann, K and L Püttmann (2017), “Benign effects of automation: New evidence from patent texts”, Working paper.