In July, 2021, the envoys of Australia, Japan, and Singapore to the World Trade Organization (WTO) made a significant announcement: The plurilateral Joint Statement Initiative on E-commerce was making excellent progress among the talks’ eighty-six members. [i] In September, the members noted further momentum, citing consensus on high-standard texts reflecting the perspectives of both developed and developing nations.[ii] These announcements continued the winding saga of one of the world’s sharply contested debates for global governance: the regulation of digital trade by the WTO.

At the WTO, digital trade has emerged as a key umbrella concept, capturing a variety of trade in goods and services in which the internet plays a central role [iii] – a far cry from the Uruguay Round’s description of the internet as an “obscure novelty.” [iv]

Indeed, the WTO was born to cater to an analogue world. Only in 1996, following the First Ministerial Conference in Singapore, did members recognize the gap and begin to draw up rules that could regulate trade in a rapidly digitizing era. [v]

Since then, the process has been keenly contested. Gridlock at the WTO has caused members to look outside and negotiate free trade agreements with countries that share economic and strategic interests. Can the WTO remain relevant and resilient as it adapts to the regulatory challenges of the digital age?

Negotiating digital trade at the WTO

At that inaugural meeting of Ministers in 1996, members came to an important agreement: They would put forth a temporary moratorium on the imposition of customs duties on the electronic transmissions of digital goods and services. Even then, digital trade was growing, and members feared the impacts of tariffs. [vi] After the moratorium was affirmed, a Work Programme on e-commerce was established, cutting across four WTO Councils: goods, services, intellectual property, and development.

A near silence ensued that initial burst of activity. Apart from the periodic renewal of the e-commerce moratorium, we saw negligible progress from 2001 to 2007. E-commerce issues were largely excluded from the negotiating agenda of the Doha round.

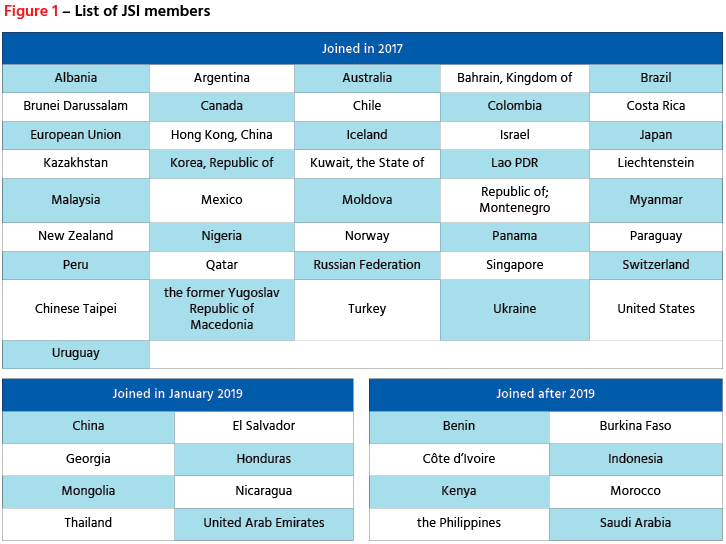

The stalemate was caused in part by the concerns of developing states, who were not willing to trade away their ability to promote their indigenous technology ecosystems. Then, at the Ministerial meetings in December 2017, seventy one WTO members gave digital trade negotiations a shot in the arm with a Joint Statement. The statement, heretofore referred to as the JSI, agreed to “initiate exploratory work towards future WTO negotiations on trade-related aspects of e-commerce.” [vii]

Momentum increased again in 2019, when seventy six WTO members agreed to work towards an outcome built by as many members as possible. [viii] China was a surprise entrant as it sought an active role rather than remain on the side lines. [ix]

Other newcomers – Indonesia, the Philippines, Cote d’Ivoire, and Burkina Faso – were also surprising. [x] Indonesia had disagreed with the original JSI members on several issues, [xi] only to announce that the initiative could serve as a bridge between developed and developing countries. Its participation would be crucial, given that its government included issues related to e-commerce when negotiating bilateral and plurilateral free trade agreements. [xii]

Meanwhile, Cote d’ Ivoire urged for a set of common principles specific to developing countries, according to their respective capacity for implementation.

While the JSI has reached a critical mass of participants, accounting for more than 90% of world trade now, several developing countries, including India and South Africa remain steadfast in opposition. [xiii]

Points of tension

In December 2020, JSI members produced a consolidated negotiating text. [xiv] India and South Africa, however, pursued a parallel track. They breathed new life into the Work Program on e-commerce and their efforts resulted in a structured discussion in July 2021 on several cross-cutting issues. [xv]

With two parallel processes gathering steam but few signs of synergy, the coming months building up to the Ministerial meetings in December 2021 are critical.

The path to overarching consensus is paved with challenges. Members are firm on several core fissures. The first regards the legal validity of the JSI process itself. India and South Africa allege that the JSI process erodes the integrity of the multilateral framework and subverts the organization’s consensus-based rules and principles. [xvi] Thus JSI members, they argue, must seek consensus among the WTO’s entire membership in order for the process to be valid. Furthermore, JSI members must garner consensus from the required proportion of members or, alternatively, negotiate a plurilateral trade agreement outside the WTO.

India and South Africa’s position is legally correct. Article X was incorporated into the Marrakesh Agreement to prevent secret and exclusive negotiations by a limited group of countries. [xvii] However, their staunch opposition did little to stymie the efforts of the JSI, which continue with gusto. JSI members maintain that the process has been inclusive. [xviii]

Within the negotiating text, three core points stand out.

The first relates to obligations relating to the free flow of data across borders – a fiercely contested issue. Several countries within the JSI, such as China, as well as those outside, such as India, have data localization mandates that compel the storage or processing of data within territorial borders. [xix]

Other countries – mostly developed nations – argue that arbitrary restrictions on cross-border data flows adversely impact the ability of companies to do business and impede digital trade. Any WTO mandate constraining the legitimate policy space available to nations on data flows strikes at the heart of data governance strategies worldwide. All members view this topic as a negotiating priority.

The second issue relates to the mandatory disclosure of source code – the fundamental component of a computer program [xx] which countries often require foreign firms to disclose, including their algorithms and encryption keys. [xxi] Many developed countries want to incorporate provisions guarding against this mandatory transfer, as it could negatively impact business interests and hamper innovation. Many developing countries argue that such restrictions hinder knowledge and technology transfers. Further, restrictions limiting national policy space on source code disclosure could harm a country’s capacity to mitigate cybersecurity threats and audit the impact of algorithmic decision-making on individuals and communities.

The third core issue is the 1996 moratorium on custom duties for electronic transmissions, and whether it should continue – or become permanent. [xxii] Citing revenue losses and increased dependence on developed world products, developing countries, again led by India and South Africa, want its impact to be reviewed. [xxiii]

Fundamentally, the debate strikes at the core of the WTO: How to strike a balance between the sovereign right of states to define domestic policy with concessions that are required to reap the benefits of the global trading system.

Many developing countries do not want to risk signing up for obligations that might constrain their hands. Given the nascency of the digital economy in the developing world, imposing standards on cybersecurity, consumer protection, or privacy through the WTO reduces the policy space available to determine governance frameworks that they feel work best at home. National, legal, and regulatory frameworks, they argue, should be in place before negotiating global outcomes. [xxiv]

In response, JSI members argue that national restrictions and arbitrary protectionism hamper the meaningful benefits of digital trade for commerce and consumers.

Competing narratives, strategic politics

No one group has relied on legal or economic arguments alone. Each has tried to win the battle of political narratives as well. For the developing world, the rallying cry has been ‘data sovereignty’: the right of nations to govern the data generated by citizens within their physical boundaries. [xxv] This narrative has been propped up by the idea of ‘data colonialism’, which refers to the practices of technology companies to extract data to consolidate global market power – at the cost of consumer welfare. [xxvi] This narrative has been burnished by government officials, civil society groups, and the private sector alike.

These concerns are not limited to the moral and ethical. Political and strategic concerns are at play too. Local technology companies and data centre enterprises stand to gain from the costs of compliance that foreign technology companies must incur. [xxvii] Predictably, they have shaped this narrative and influenced the stances taken by their governments at the WTO.

The developed world also has tried to mould the narrative. In 2019, the Osaka Track announced at the G20 meetings its own call to action for “data free flow with trust’, arguing that digital trade flows are necessary for harnessing innovation. [xxviii]

Lobbying for domestic regulatory changes in several developing countries – India, Indonesia, and Vietnam – has been rife. Technology companies have also sought to influence how negotiators from the European Union and the United States engage at the WTO. [xxix] The European Services Forum (ESF), a lobbying group comprised of Apple, Google, Huawei, Orange, and Vodafone, is pushing for a transatlantic axis to safeguard cross-border data flows and legal obligations on digital trade. [xxx]

Breaking the gridlock

This gridlock need not end in stalemate. Countries on the opposing ends of the spectrum are not all locked in adversarial geopolitical relationships. The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue has JSI members Australia and Japan partnering with staunch JSI opponent India.[xxxi] All the countries share positive bilateral relationships across sectors.

Arguably, there is no insurmountable ‘trade war’ at the WTO. Opportunities for engagement and dialogue exist. It is imperative for all members to work out a mutually acceptable way of getting everyone in the same room.

India and South Africa have valid critiques of the JSI. However, one must ponder whether the alternatives will further their strategic interests. If e-commerce rules do not fructify within the WTO, negotiations will shift to the spaghetti bowl of trade agreements outside the WTO.

Several agreements, including the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), and the Digital Economic Partnership Agreement (DEPA) already incorporate obligations on e-commerce. That leaves the WTO with the developing world and smaller nations.[xxxii]

The WTO’s consensus-based framework allows all countries to not only have a veto but also to work in coalitions that punch above their individual weights. Free trade agreement negotiations are not always so equitable, as institutional mechanisms are not as clearly defined. Sitting on the margins is also not an option. As a critical mass of countries begin signing on to trade agreements, countries not in the mix become unwitting standard takers should they want to participate in regional or global trade networks.

The WTO’s negotiating function can be revitalized without drifting off into the territory occupied by the JSI. Genuine progress can be made through streamlining and rejuvenating the Work Programme on e-Commerce, providing space for ample debate on issues that JSI members consider most relevant, such as data flows or source code disclosure.

The developing countries can negotiate exceptions to obligations crafted in the negotiating text. For example, the e-commerce chapter of RCEP incorporates the exceptions of ‘legitimate public policy objectives’ and ‘essential security interests’ to justify domestic mandates restricting cross-border data flows. Exceptions serve as an important balancing tool for preserving decision-making space without impeding the passage of the rule itself.

The outcome need not be an ‘all or nothing’ arrangement which compels consensus on all issues of digital trade.[xxxiii] Instead, the modular approach adopted in the DEPA – the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement between Singapore, Chile, and New Zealand – can be adopted, whereby countries can pick and choose ‘modules’ with which they want to comply. Through different combinations of modules, a global legal architecture can amass incrementally while developing countries think through and implement domestic regulations that work for the interests of their citizens.

The principles and governance architecture of the WTO plays a talismanic role in global governance. Undoubtedly, the forum has its imperfections and has often been captured by the hegemonic tendencies of the powerful. Yet it remains the closest the world trading system can come to guaranteeing a level-playing field. As nation states wade the unchartered waters of the digital world, it is imperative that these institutional mechanisms be refined and updated. Astute consensus building in lieu of obstinate abstention is the need of the hour.

Arindrajit Basu is Research Lead at the Centre for Internet & Society, India, where he focuses on the geopolitics and constitutionality of emerging technologies.

To read the full commentary from the Hinrich Foundation, please click here.