An Enhanced Trade Partnership (ETP) between the UK and India was agreed in May 2021 with investment from India creating jobs in the health and technology sectors in the UK, as well as lowering non-tariff barriers of UK fruit and medical device exports. Negotiations for a UK-India Free Trade Deal (FTA) are due to start in November, with a vision of agreeing an ‘Early Harvest Agreement’ by March 2022 as a precursor to the full FTA. The Early Harvest Agreement would set out goods and services that would qualify for tariff free access into the UK and Indian markets.

What’s the current situation?

Metals and machinery are main UK goods that are exported to India, with refined oil and clothing the main UK imports from India. Agriculture accounted for 16% of India’s economy (value added) in 2019, after the industrial sector which makes the highest contribution to India’s GDP at almost 25%. In contrast, agriculture comprises 0.6% of the UK economy (2019) with the services sector the main contributor at over 70%.

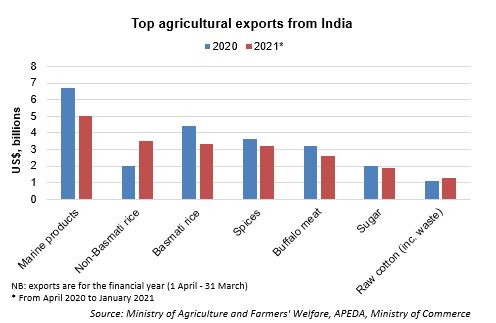

Top Indian food exports are rice, marine products (fish/seafood), spices and buffalo meat.

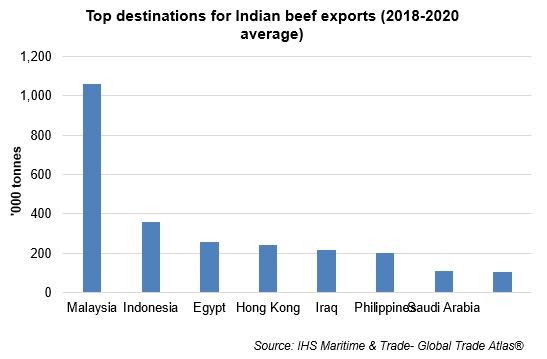

India was the fifth largest global beef producer, based on the 2018-2020 average, ahead of Australia and Argentina. Despite, the traditional notion that India is mainly a vegetarian country, a recent report by Natarajan and Jacob[1] claims that the extent to which this is true may be exaggerated. The report estimates that only 20% of Indians are vegetarian, with ‘cultural and political pressures’ leading to the under-reporting of eating meat. India’s main religion is Hinduism, which considers the cow to be sacred, but Natrajan and Jacob’s work estimates that 15% of India’s population (or 180 million Indians) consume beef, which is 96% higher than official figures.

India’s main export destinations for beef are in South-East Asia, the Middle East and Egypt. India’s main competitor for these markets is Australia. Indian cattle are mainly raised on natural feed so costs are lower compared with systems that use antibiotics, growth enhancers and hormones. However, the Indian beef sector has obstacles, such as bans on the sales of live cows for slaughter to contend with, as well as the general preference of Australian beef.

What’s the potential for agri-food trade between UK and India?

For the sectors shown above, there is not much, if hardly any trade between the UK and India. The current tariff rates will be a key factor here with India’s average tariff rates on most products, including food, higher than those for the UK. India also has a higher number of non-tariff measures, such as sanitary and phytosanitary conditions, quantitative restrictions and safeguards compared to the UK and so an FTA between the UK and India could provide beneficial for the UK if there is some relaxation on this front from India.

From a UK perspective, there is certainly potential in the Indian market for value added dairy products such as cheese. As mentioned above, although fresh dairy products are more widely consumed in India, there has been growth in demand for value added dairy products. While demand for higher value dairy products is at a relatively low base, the growing middle class and huge population in India provides opportunities.

There may also be some potential for UK sheepmeat exports to India. At the end of 2018, India gave access to British sheep meat imports for the first time. As with value added dairy products, although Indian sheep meat consumption is relatively low, there is opportunity for this market to grow.

Amandeep Kaur Purewal is a Senior Analyst in the policy team. Potential speaker and discussion topics from AHDB’s market intelligence team as well.

To read the full commentary by Amandeep Kaur Purewal on the AHDB, please click here.