Trade is central to development in Africa. A long history of economic thought, theory and practice underpins this proposition. However, I do not seek to interrogate the foundational principles of international trade, but rather to highlight issues that underscore the key role of trade as a driver of growth, sustainable development and poverty reduction. This is not automatic. It requires trade policies that are dynamic, inclusive and responsive to both opportunities and constraints in constantly changing national, regional and global contexts.

Positive and negative externalities

There are two main pathways – public and private – through which international trade generates resources for sustainable development. Through the public pathway, governments derive revenues from international trade through taxes on imported and exported goods and services, taxes on incomes and profits from trade-related production and transactions and by directly receiving the proceeds from exports. The private pathway is through returns on investment and other transactions including remittances. Both pathways can further generate positive externalities and indirect financing for economic and social development. Both pathways, however, can also generate negative externalities, including unsustainable levels of inequality.

Trade, poverty, inequality and growth

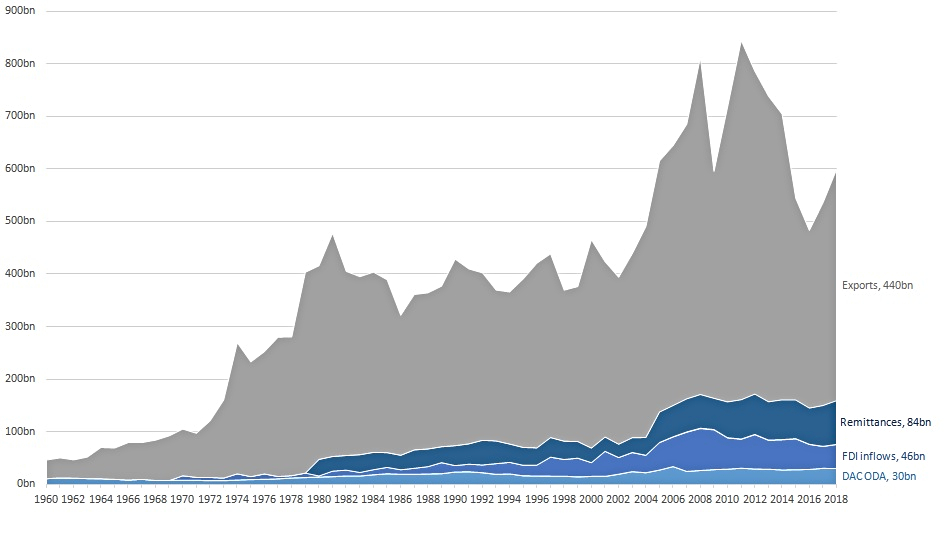

Trade revenues are multiple resource flows from other sources into Africa. As shown in figure 1, over the last decade export revenues have accounted for more than three times the value of remittances, FDI inflows and official development assistance taken together. Exports have been worth approximately 17 times as much as overseas development assistance, such as development aid, during this period.

Figure 1. Africa’s total exports, remittances, FDI inflows and DAC official development assistance, 1980-2018, constant 2018 US$

Sources: Exports from IMF DOTS 2020; FDI inflows from UNCTAD Stat 2020; Official Development Assistance from OECD ODA 2020; and remittances estimates from World Bank 2020. Note: Reliable FDI data is available only from 1970 and remittances data from 1980, represented above accordingly.

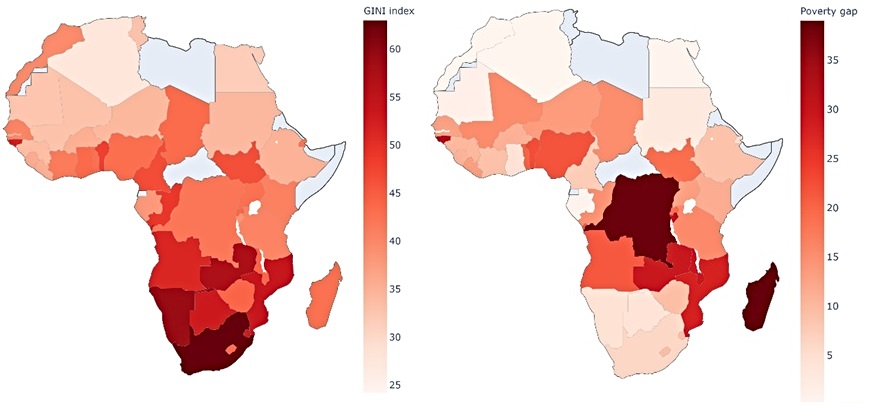

Poverty and inequality in Africa are pervasive, as can be seen in figures 2 and 3. Much of this outcome can be attributed to the historical legacy and current reality of African economies undergirded by trade regimes that are mainly dependent on producing and exporting low value products (and services), often subject to severe price fluctuation. Africa, with 17% of the world’s population, accounts for about 3% of world trade.

Figure 2. Development indicators 2020. Right: Gini Index (higher = greater inequality), 2019 or latest available data. Left: Poverty gap (share of population with less than PPP $1.90 per day), 2019 or latest available year.

Formal trade between African countries is also low, at an average of 15% of total trade during 2016–18. Africa’s trade challenges are compounded by the strong prevalence of informal cross border trade in both goods and services of even lower value transactions. Informal cross border trade is associated with the high rates of poverty that compel people to seek a living by buying and selling small quantities of fast-moving merchandise, especially food items, and providing low skilled services. It is fuelled by such constraints as high trade costs, expressed through a lack of access to credit and finance and inefficient border processes. Women constitute the majority of informal cross border traders, accounting for as much as 61% of all informal cross border transactions in the Lagos-Abidjan corridor, for example.

Figure 3. Female informal cross border traders crossing Aflao on the Ghana-Togo border. Credit: UNECA.

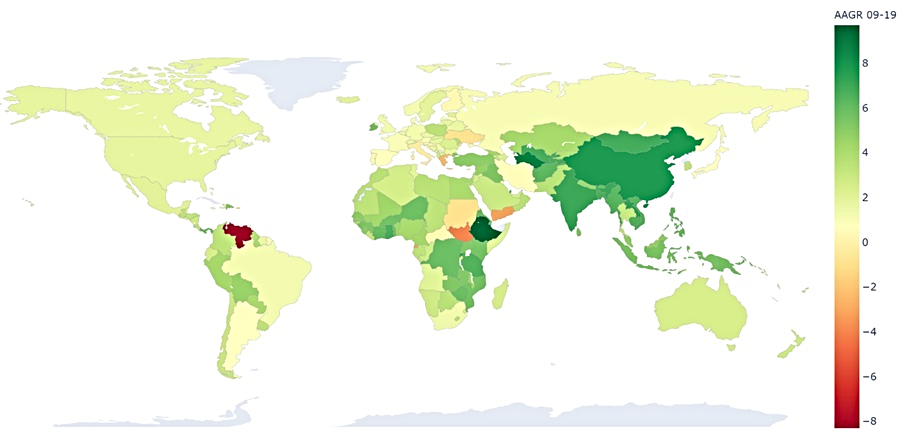

However, until the COVID-19 pandemic struck in early 2020, several of the fastest growing economies in the world were in Africa, mainly driven by diversification and trade expansion, with positive externalities on poverty reduction and other indicators of general welfare. For these countries, GDP growth rates during 2020–24 were expected to be between 6% in Burkina Faso and 8.3% in Senegal (as shown in figure 4). Even with COVID-19, African countries are forecast to retain a relatively higher degree of growth in 2020 and 2021 (as shown in figure 5).

Figure 4. Average annual growth rate: 2009 to 2019.

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook April 2020Fig. 6 Forecast average growth rate under COVID-19: 2020 and 2021. Source: IMF. IMF World Economic Outlook April 2020.

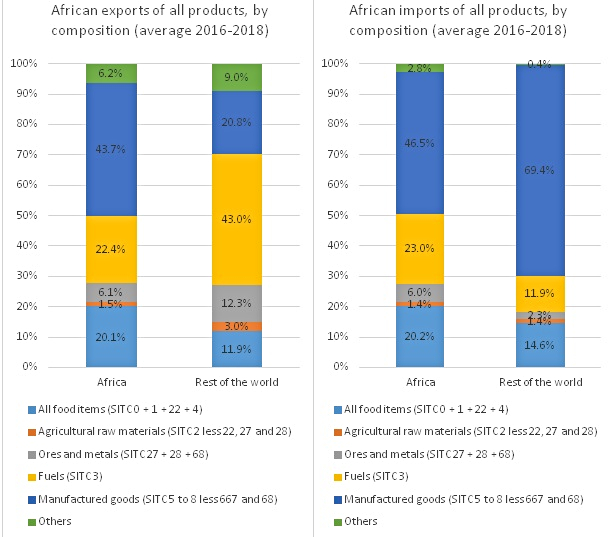

An often-overlooked detail is that the composition of trade tends to vary strongly whether the destination of Africa’s exports is the African market or the rest of the world. As shown in figure 6, primary commodities account for over 70% of Africa’s exports. But the share of manufactured goods in intra-African exports is about 45%, with primary commodities accounting for a third.

This is why there has been so much interest in the African Continental Free Trade Area Agreement (AfCFTA), which entered into force on 30 May 2019. Analysis carried out at the UN Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) shows that, if effectively implemented, the agreement could help boost intra-African trade. The ECA projects – on the basis of computable general equilibrium modelling – a positive effect on Africa’s overall GDP, exports and welfare. The benefits will be most significant for intra-African trade, which could increase in value between 15% (US$50 billion) and 25% (US$70 billion) by 2040, depending on the ambition of the reform as compared to a baseline scenario with no AfCFTA. More than two-thirds of the gains in intra-African trade will be captured by industrial sectors with textile, wearing apparel, leather, wood, paper, vehicle and transport equipment, electronics and other manufactures expected to benefit the most. Gains in the agriculture and food sectors would also be substantial, particularly for meat products, milk and dairy products, sugar, beverages, vegetables, fruits, nuts, rice and other grains.

Figure 6. African exports and imports by composition 2016-18.

Source: Calculation from UNCTADstat

The AfCFTA is therefore a central tenet of African trade policy. It is a continent-wide initiative for maximising value from trade, economic diversification, the promotion of intra-regional trade and a better and more stable integration into regional and global value chains. Associated policy reforms include bringing trade costs down by improving border processes and other trade facilitation measures, which are essential for productivity and competitiveness. More efficient services sectors can help to build and upgrade regional value chains. These are all key enablers for a more diverse and complex production and trade structure, for managing volatility and providing a more stable path for sustainable growth and development. These elements are now more important than ever in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and the demographic imperative in Africa to increase the number and quality of jobs.

Trade agreements

Trade agreements provide the framework for the articulation of trade policy. They ensure predictability and legal certainty for the contractual commitments embodied in the exchange of goods and services. But they also shape development and other outcomes in the outworking of positive and negative externalities from trade.

African trade agreements can be divided into four main categories (see annex).

1. World Trade Organization agreements that apply to its 44 African member countries. An additional nine African countries are in the process of acceding to the WTO or are observers.

2. African regional trade agreements which include the continent-wide AfCFTA and sub-regional trade agreements of the main regional economic communities (RECs) such as the East African Community (EAC), the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC), the Southern African Customs Union (SACU), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the Arab Maghreb Union (AMU).

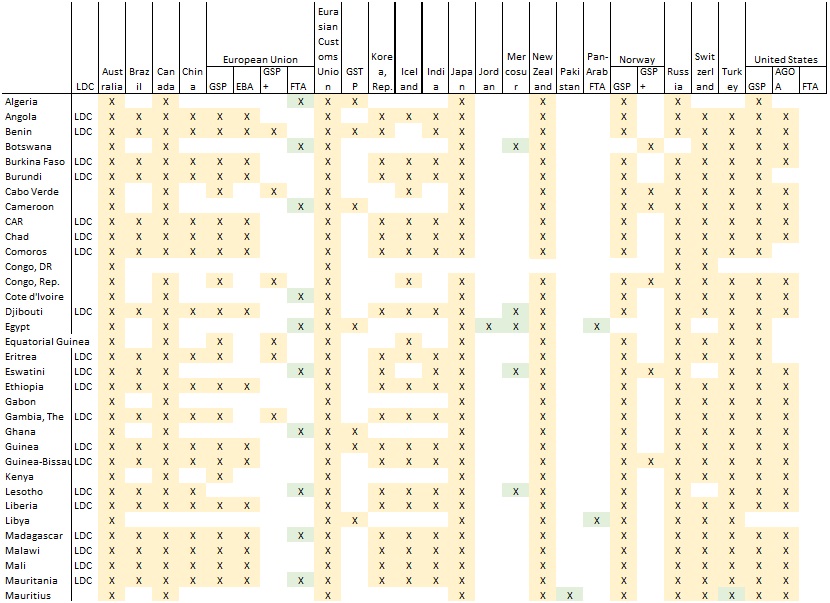

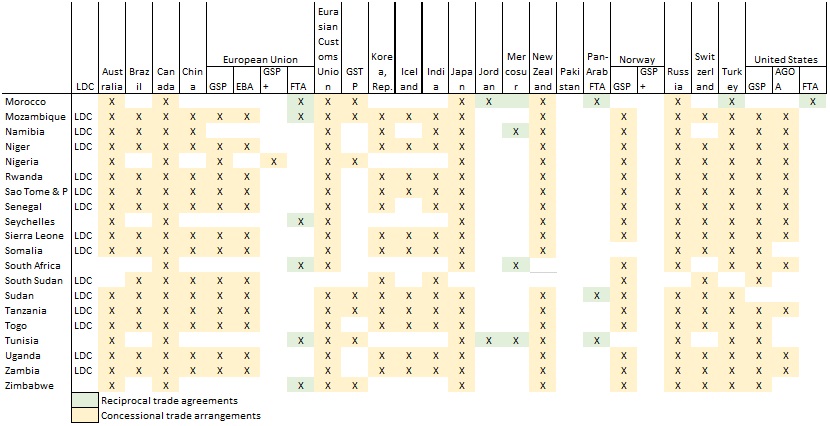

3. Concessional trade arrangements such as the European Union’s Every Thing But Arms (EBA) for least developed countries; the United States’ Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) for eligible African countries; and the Generalised System of Preferences (or GSP) and enhanced GSP (GSP+) of several OECD countries; as well as a number of schemes for least developed countries, including of China and India.

4. Reciprocal trade agreements such as the Economic Partnership Agreements between the EU and three groups of African countries in East and West Africa (still to be finalised) and Southern Africa (finalised); the Euro-Mediterranean Agreement between the EU and North African countries; the EU-Algeria Free Trade Agreement; and the USA-Morocco Free Trade Agreement.

In 2013, China announced a ‘Belt and Road Initiative’, which provides a mix of trade concessions and financing for trade-related infrastructure. Mauritius is negotiating free trade agreements with China and India. The US and Kenya have announced negotiations for a free trade agreement. It is understood that in relation to African countries, the United Kingdom will roll over the EU arrangements on EBA (Everything But Arms), GSP (Generalised System of Preferences) and GSP+ pending its own negotiations of a trading framework with African countries. The UK already has agreements with Morocco, the SACU (Southern African Customs Union) group, Tunisia and a group of Eastern and Southern African countries (Madagascar, Mauritius, Seychelles and Zimbabwe).

Trade matters for Africa

The central role of trade in development requires that trade policies, trade agreements and concessional arrangements are monitored, assessed and analysed in relation to positive and negative externalities. Key issues for analysis range from structural changes to the economy, regional imbalances, and poverty to employment, decent work and gender equality, and from technological change including digitalisation to public health and climate change.

There is a good case for independent work that (1) systematically monitors trade negotiations in which African countries are engaged (2) assesses the impact of trade agreements and policies in Africa and (3) identifies practical policy measures and other changes to improve the developmental impact of trade. An emerging question that also deserves attention is, how will the UK’s new trade policy affect Africa and other developing countries?

LSE’s Firoz Lalji Centre for Africa is well placed to become a repository of real time information on current trade negotiations through which African countries are engaged via an Africa Trade Negotiations Monitor. It will allow not only trade experts and policy makers but the whole community of scholars to keep track of the trade rules that shape development outcomes. This can be complemented with analytical work on trade policy impacts with a view toward the publication of an annual Africa Trade Year Book.

Annex: Africa’s Trade Agreements

Annex: Africa’s Trade Agreements (continued)

Sources: WTO RTA database (2020) and UNCTAD, Handbook on Duty-Free Quota-Free and Rules of Origin (2017). Notes: GSTP is Global System of Trade Preferences among Developing Countries and the Pan-Arab FTA grants preferential access to the markets of Iraq, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Syria, UAE, Yemen.

♣♣♣

David Luke is coordinator at the African Trade Policy Centre, UN Economic Commission for Africa.

To read the original blog post, click here.