What a difference two months can make. In May, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC), the world’s largest chipmaker, lost the business of Huawei Technologies—its biggest Chinese customer and the source of 13% of its revenue—as a casualty of geopolitical jockeying between superpowers. But TSMC shareholders took the loss in stride. And by late July, after a stumble by rival Intel, TSMC’s stock had risen almost 50% since May, making it one of the world’s 10 most valuable companies.

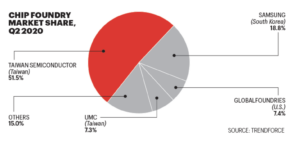

May’s low and July’s high have something in common: They both reflect TSMC’s distinctive role in the global tech economy. Although far from a household name, TSMC controls roughly half of the world’s contract chip manufacturing. Brand-name companies that design their own chips—most notably Apple—rely on TSMC’s world-class production so they don’t have to spend tens of billions to build their own factories. Crack open your iPhone and you’ll find a chip from TSMC. If you could crack open an American guided missile, you’d likely find one there too. Its prowess has elevated TSMC to No. 362 on the Global 500, with $35 billion in revenue. Today it gets 60% of sales from the U.S. and about 20% from mainland China.

But TSMC’s central place in the silicon ecosystem makes it particularly sensitive to the counterpunches of Sino-American trade tensions. As relations between China and the U.S. deteriorate, each is determined to insulate its supply of semiconductors from attack by the other—which means redefining their relationships with TSMC. As the chipmaker charts its course between the antagonists, the stakes for both countries and the broader tech industry are substantial.

“Semiconductors are such a big weapon because they’re one of the clearest choke points in the global technology trade,” says Matt Sheehan at MacroPolo, the Paulson Institute’s China-focused think tank. “There are good substitutes to a lot of other tech, but there’s not a good substitute for TSMC.”

Still, being irreplaceable doesn’t make a company invulnerable. TSMC chairman Mark Liu admits to Fortune that trade headwinds are creating headaches. “Our work relies on the free flow of knowledge and the free flow of trade,” he says, “which has no doubt been suppressed.”

Founded in 1987, TSMC initially provided overflow capacity to chipmakers like Intel that had their own foundries or “fabs.” When demand for chipsets boomed in the 1990s along with personal computers, TSMC’s revenue soared as it served “fabless” U.S. companies like Nvidia and Qualcomm.

“Suddenly entrepreneurs didn’t need billions of dollars to open their own foundries, they could use TSMC,” says Daniel Nenni, founder of chip information forum Semiwiki. By not engaging in chip or product design, TSMC could assure clients it would never steal designs and compete. Talented chip designers were able to tap TSMC’s manufacturing to launch their own start-ups. “Hundreds of companies resulted from this transformation,” Nenni says.

The company’s biggest breakthrough came in 2011, when it began partnering with Apple. Apple now accounts for roughly 23% of TSMC’s business, and TSMC is the sole manufacturer of processors for iPhones and iPads.

TSMC was attractive to Steve Jobs’ juggernaut in part because of its reputation for protecting intellectual property. Apple and its previous chip manufacturer, Samsung, were exchanging bitter lawsuits over alleged IP theft when TSMC entered the scene. According to Richard Thurston, who served as TSMC general counsel from 2002 until 2014, Apple audited TSMC’s trade-secrets protocols and found “we were doing things even they weren’t doing.”

At TSMC, employees, customers, and suppliers all sign nondisclosure agreements. The company’s 16 manufacturing sites in Taiwan are firewalled from each other, preventing hackers from finding a singular point of access. Even low-tech theft is heavily guarded against. In some fabs, printer paper is lined with metallic strips that activate airport-style gate sensors at the exits if an employee tries to leave with notes in a pocket.

The company also has a reputation for flawless execution. Each semiconductor contains billions of transistors; for the chip to work, each transistor needs to be made perfectly. Although the manufacturing equipment TSMC uses is available commercially, the processes TSMC developed to utilize it are virtually inimitable. Philip Wong, vice president of corporate research, puts it this way: “I could buy the same tennis racket as Serena Williams, but I’m not going to play as well as her.”

China would dearly love to up its game. TSMC is China’s biggest contract supplier, making chips for the likes of smartphone giant Xiaomi, computer manufacturer Lenovo, and electric-vehicle makers. Recently Beijing has accelerated its push for silicon independence. China’s Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp. (SMIC), a company founded in 2000 with government support, secured $2.5 billion in state funding this May and raised another $6.6 billion in July through a share offering in Shanghai. But SMIC’s technological capabilities remain generations behind TSMC’s. So do its sales: In 2019, SMIC had revenue of roughly $3 billion, while TSMC sold $7 billion worth of chips in mainland China alone.

I could buy the same tennis racket as Serena Williams, but I’m not going to play as well as her.

PHILIP WONG, VP, CORPORATE RESEARCH, TSMC

Without a cutting-edge chip manufacturer, China’s tech economy remains vulnerable, and this spring the U.S. exploited that vulnerability by severing TSMC from Huawei, the telecom equipment manufacturer. The White House has long pressured allies and companies to block Huawei’s development, arguing that Huawei can intercept sensitive data with its communications gear and share it with China’s government. (Huawei has denied that it would do so.) In May, the U.S. Commerce Department issued a regulation that effectively prohibited TSMC from selling chips to Huawei if it wanted to keep doing business with U.S. firms; TSMC obliged.

The timing of the Huawei ban was intriguing. Just hours before it was issued, TSMC had announced it would invest $12 billion in building a fab in Arizona. Alex Capri, a visiting senior fellow at the National University of Singapore, sees that plant as “a concession,” with TSMC expanding production in the U.S. to gain political leverage in Washington.

Leaders in Beijing may have seen it that way too. They sent fighter jets to buzz Taiwan’s airspace a total of eight times in June, upping the pressure on TSMC’s home base—an island the Beijing government claims sovereignty over. The flyovers were a sobering reminder that an escalating Trump-vs.-China trade war could result in something hotter. A major disruption of TSMC’s fabs would have enormous ripple effects in tech—not least, jacking up the price of an iPhone.