The United States and many other countries view the World Trade Organization as the forum for global trade rules that support market economies. One of the challenges for the WTO going forward is what to do with the important Members whose economic systems are not anchored in market economic principles. While China is the most frequently mentioned WTO Member whose economic system is causing massive disruptions for market economies, there are other countries with important sectors that are state-owned, controlled and directed. The United States, European Union and Japan have been working on proposals for modifications of WTO rules to address distortions flowing from massive industrial subsidies and state controlled sectors that do not operate on market principles.

While WTO reform is not likely to see serious engagement by WTO Members before the COVID-19 pandemic is brought under control, the sharp contraction of economic activity in many countries is highlighting the importance for WTO Members actually addressing the role of the state in industry and rule changes needed to avoid the massive distortions that state involvement too often created.

Oil and Gas as an Example

Few industrial sectors have as much state ownership and control as the oil and gas sector. While there are countries with privately owned producers, much of the world operates with producers that are state owned or state controlled. Since the 1960s, a number of countries have engaged in cartel-like activity to collectively address production levels to achieve desired price levels. While many of these countries are part of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (“OPEC”), OPEC meets with other countries as well in an effort to achieve production and pricing levels. Current OPEC members include Algeria, Angola, Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Venezuela.

The activity has resulted in artificial pricing levels in export markets as compared to prices in home markets of OPEC members and periodic price shocks based on collective action. Large price increases in the 1970s led to high levels of inflation and rapid changes to manufacturing operations in some countries.

1.Economic contraction as countries struggle to limit spread of the coronavirus

There has been a sharp contraction in demand for petroleum products in 2020 as countries have shut down movement of people in an effort to control the spread of COVID-19. Air travel has been decimated in many parts of the world and there are significant reductions in automobile travel. Manufacturing has also seen significant reductions. The contractions have resulted not only in national reductions in use of petroleum products but also international reductions both directly (reduced air traffic and ship traffic) and because of disruptions to supply chains which have reduced downstream production.

The U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission released a staff research report on April 21, 2020 entitled “Cascading Economic Impacts of the COVID-19 Outbreak in China” which reviews information on the wide range of economic impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic as felt in the U.S. https://www.uscc.gov/

“The standstill in Chinese production and halt in flows of goods and people has drastically depressed Chinese demand for energy products such as crude oil and liquified natural gas (LNG), adding pressure to an oil supply glut that had materialized at the end of 2019.99 In December of 2019, Institute of International Finance economist Garbis Iradian had forecasted a supply glut, pointing to high output from Brazil, Canada, and the United States.100 The COVID-19 outbreak exacerbated this challenging outlook. As the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) reported in April 2020: ‘The largest ever monthly decline in petroleum demand in China occurred in February 2020.’101 Chinese oil demand ‘shrank by a massive 3.2 million barrels per day’ over the prior year.102 Research by OPEC forecasted China’s 2020 demand for oil will decrease by 0.83 million barrels per day over 2019.103 As the largest oil importer,104 Chinese oil consumption has a significant impact on global demand. In 2019, China accounted for 14 percent of global oil demand and more than 80 percent of growth in oil demand.105 Following the outbreak in China, the OPEC Joint Technical Committee held a meeting on February 8 to recommend new and continued oil production adjustments in light of “the negative impact on oil demand” due to depressed economic activity, “particularly in the transportation, tourism, and industry sectors, particularly in China.”106 In LNG markets, on February 10, Caixin reported Chinese state-owned oil giant China National Offshore Oil Corp. (CNOOC) requested a reduction of an unknown quantity in LNG shipments, invoking a “force majeure” clause due to COVID-19.107 S&P Global Platts, an energy and commodities analysis group, stated China’s LNG imports in January and February fell more than 6 percent over the same period in 2019.108

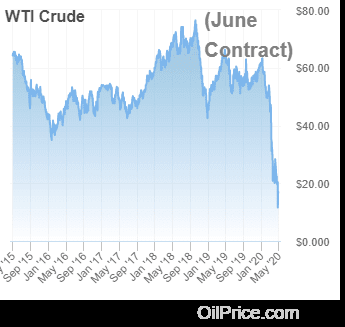

Prices have also dropped in this period. OPEC’s reference price index fell from $66.48 per barrel in December 2019 to $55.49 per barrel in February 2020, a drop of 19.8 percent.109 These price cuts are causing financially strapped* U.S. energy producers to cut back investment in oil and gas projects as profits erode. The U.S. Energy Information Administration forecasts that the current drop in oil prices will lead to lower U.S. crude oil production beginning in the third quarter of 2020.110″

The complete report is embedded below (footnotes 99-110 can be found on page 22 of the report).

2. State-owned or controlled oil companies create further crisis

With a sharp contraction in oil demand, one would expect falling oil prices and reductions in global production over time. OPEC efforts to achieve reductions in production amongst themselves and Russia didn’t work out with Russia walking out of talks to reduce production to prevent further price declines. Russia and Saudi Arabia then engaged in a price war which resulted in further sharp price reductions in March and early April, large surpluses of oil in the market, with dwindling storage capacity for surplus production. See, e.g., https://en.wikipedia.

3. April Agreement to Reduce Production Beginning in May and June 2020

The United States, concerned with the collapse of oil prices and the effects on U.S. producers and oil/gas field companies, engaged in outreach to both Saudi Arabia and Russia to seek a solution. OPEC members, Russia and many others (including the United States) agreed to global production reductions of close to 10 million barrels/day beginning in May and carrying through June, with smaller reductions for later periods, in an effort to bring about balance between supply and demand. See, e.g., April 12, 2020, AP article, “OPEC, oil nations agree to nearly 10M barrel cut amid virus,” https://apnews.com/

Because the agreement kicks in at the beginning of May, the continued production and reductions in available storage for oil resulted in further declines in oil prices, with prices on April 20 going negative for the first time in history. Prices have recovered somewhat in the last several days. https://www.cnbc.com/

WTO Challenges

Joint action during the global COVID-19 pandemic may be understandable and in keeping with the resort to extraordinary measures by governments during the crisis to preserve health and economies. Nonetheless, the extraordinary distortions that flow to global commerce from joint government activity limiting production of oil and gas products or establishing minimum prices for export have been ignored within the GATT and now the WTO for decades. This is unfortunate as the distortions affect both competing producers of the products in question in other countries and also downstream users and consumers more broadly. The overall distortions over time are certainly in the trillions of dollars.

GATT Art. XX(g) permits governments to enforce measures “relating to the conservation of exhaustible natural resources if such measures are made effective in conjunction with restrictions on domestic production or consumption.” While there have been some cases where Art. XX(g) has been examined, actions by OPEC or OPEC+ countries to limit production (and hence exports) have never been challenged.

While there are national antitrust laws in many countries, such laws (such as those in the United States) don’t make government interference in the economy or government restrictions on export actionable despite the harm to consumers and to downstream manufacturers.

In a consensus based system like the WTO, the likelihood of obtaining improved rules on state-owned or state-invested companies or to restrict governments’ ability to unilaterally or jointly restrict production and exports seems implausible. This is especially true on oil and gas with Saudi Arabia and Russia as WTO Members. The US-EU-Japan initiative hasn’t yet fleshed out possible rule changes for state entities, so one may see some efforts in the coming years that could be useful if accepted by the full membership. But if there is to be meaningful WTO reform, agreeing on rules for the actions of governments that affect production and trade in goods and services is clearly of great importance. Without such rules, the WTO will not actually support market economies in critical ways.

Modifying antitrust laws is the other option, but one which legislators have been unwilling to address over the last fifty years. It is not clear that there are current champions of such modifications in the United States or in other major countries.

Conclusion

There are many sectors of economies that are being seriously adversely affected by efforts to control the spread of COVID-19. Governments are taking extraordinary actions to try to prevent their economies from collapsing under the strains of social distancing.

The oil and gas sector is one where there has been significant negative volume and price effects. Unfortunately the extent of the negative volume and price effects is driven in large part by the actions of governments who are preventing the global market for these products from functioning correctly, just as government actions have interfered in the functioning of these markets for the last fifty-sixty years.

The recent agreement to slash global production by nearly 10 million barrels per day was needed in light of the extensive government interference that has characterized the market and the actions by Russia and Saudi Arabia in March and early April.

More importantly, the long-term government involvement and interference with the functioning of the sector should cause trade negotiators and legislators to be looking at how to reform the WTO and/or modify national laws to prevent government ownership, control or cartel-like actions from distorting trade flows and economies. The need is pressing, but don’t hold your breath for action in the coming years.