There is a paradox in the global debate about trade. It has never been easier to trade internationally, but global trade is poorly understood. Consumers can go to a platform like eBay, choose a product from another country, pay and await arrival, often instant for a service. Yet when world leaders debate trade openness and restrictions, they often sound as if nothing had changed in real trade for the past hundred years. The debate is still centred on tariffs, and the perception is that trade is the export of one product, produced in one factory, from one country to another.

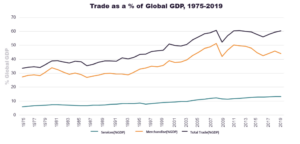

The reality is that substantially more complex trade is unfolding behind that purchase on eBay or any other cross-border transaction. One consumer purchase sets off other transactions, from supplier to platform and delivery lead, and between logistics providers. Meanwhile businesses small and large are managing the same processes at far greater scale, and integrating them into their chains of production. As a result we can get more, and pay less, for products from around the world, than ever before. It is no wonder that trade as a percentage of global GDP has been rising.

This paper introduces a series of essays providing facts and new perspectives on trade that take stock of modern trade flows and outline what they mean for trade policy. To set the scene, we start with five important considerations about global trade today.

1. We are trading more goods and services than ever before. Since 1983 global goods exports have risen dramatically from $1.8 trillion to $18.4 trillion. On top of this we trade $5.9 trillion services, though some suggest this figure is a serious under-estimate. Considering trade as imports and exports, we therefore trade on average, globally, $7000 per person per year. Global GDP has also risen alongside global trade

2. More countries are active in global trade. As can be seen below the share of exports from Asia has gone up dramatically. The growth of China is well known, with US trade data showing total trade between the two countries growing from $5 billion in 1980 to $660 billion in 2018. There are other examples. South Korea is now one of the world’s top ten exporters, and India’s share of world services trade increased by seven times from 1995 to 2018. But even in other regions some individual countries have enjoyed significant growth, trade between US and Mexico for example tripling since 1994, similarly between Poland and EU countries since 2004. Meanwhile developed countries continue to enjoy trade growth even if their share of global trade has reduced. Clearly a challenge remains to increase trade in some countries.

3. Trade has moved beyond finished goods. A single car contains around 30,000 components, and for example for those made in the UK it is estimated that more than half are imported. Those imports include goods, such as the car seats, and services, such as sat-nav systems. The car is likely to be supplied internationally alongside other services such as warranty and servicing. Companies supplying parts can be as significant as brand car makers to the global economy, for example Adient, who specialise in car seats as well as other components, claim their products are part of one-third of all cars. The car industry is one illustration of networks of trade, known as global value chains, with estimates that these cover 70% of global trade. A very different example is provided by online sales, such as the Apple App store estimated to have facilitated $500 billion of billings and sales in 2019.

4. There are more rules and regulations governing trade. The formation of the World Trade Organization in 1995 broadened the international rule-set for trade beyond goods tariffs to regulations, services and intellectual property. This was followed by significant growth in free trade agreements between two or more countries covering a similarly wide range of topics. These agreements take away border tariffs but also include demands on domestic regulation. Domestically we have seen a rise in regulations relating to the supply of goods and services particularly in developed countries, often drawing on international standard setting bodies. So we have more trade, but it is regulated trade rather than textbook free trade.

5. Trade agreements, and the thinking behind them, are outdated. It is now 25 years since eBay was founded and yet there is no global rule set for e-commerce. An international trade agreement for information-technology, updated just a few years ago, still doesn’t include services like search engines, social media and app stores. Behind the outdated rules lie dated conceptual frameworks common among the policy making community. Tariffs on industrial goods were economically damaging when trade was mostly from factory to another country, but in a world of supply chains and accompanying services trade they simply feel like an anomaly. The approach to services trade enshrined in the WTO since 1995, of four modes of supply, is neither commonly understood or particularly useful in identifying barriers to trade. Diverse regulations are a huge issue not addressed comprehensively in trade agreements and often left to the market power of multinationals through their supply chains, disadvantaging smaller companies. Our thinking about trade has to change.

Conclusion:

The benefits of global trade are threatened by outdated thinking. While trade has been growing, so have the concerns in many countries from politicians and public thinking the decline of big factories means their countries are losing out. We are in danger of losing the benefits of trade because so few can explain them satisfactorily. It is time to update our understanding, our narratives, and ultimately the rules around trade.

David Henig is Director of the UK Trade Policy Project.

To read the original blog post, click here.