In recent years, global trade relationships have shifted substantially, in many ways reversing a decades-long multilateral drive toward more open trade. I know how dizzying these shifts have been from my own experience as a US trade negotiator over the past three decades. It’s too early to tell whether these shifts are a temporary setback or, instead, a terminus for the multilateral trading system, but it’s not too soon to assess how US policies are faring amid these changes.

After World War II, a multilateral push toward freer and wider trade transformed the global economy. Tariffs and barriers fell, and more goods crossed more borders. It happened in phases, neither consistently nor all at once. A first phase started with the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), with the United States seeking to build up free markets to counter global threats posed by the Soviet Union. A more recent phase included the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995, and China and many of the former parts of the Soviet Union, including Russia, joining the multilateral trading system.

In the first two decades of the twenty-first century, however, as the WTO stumbled to negotiate new trade agreements, this trading system began to break down. Without multilateral progress, more nations sought to negotiate free trade agreements (FTAs). Now, industrial policies are proliferating and countries are focusing on “strategic” trade relationships, approaches generally at odds with the multilateral trading system first established in 1947. And this latest trend is not surprising given the vacuum left by the decline of the WTO and the disruptions in trade brought on by COVID-19 and Russia’s war in Ukraine.

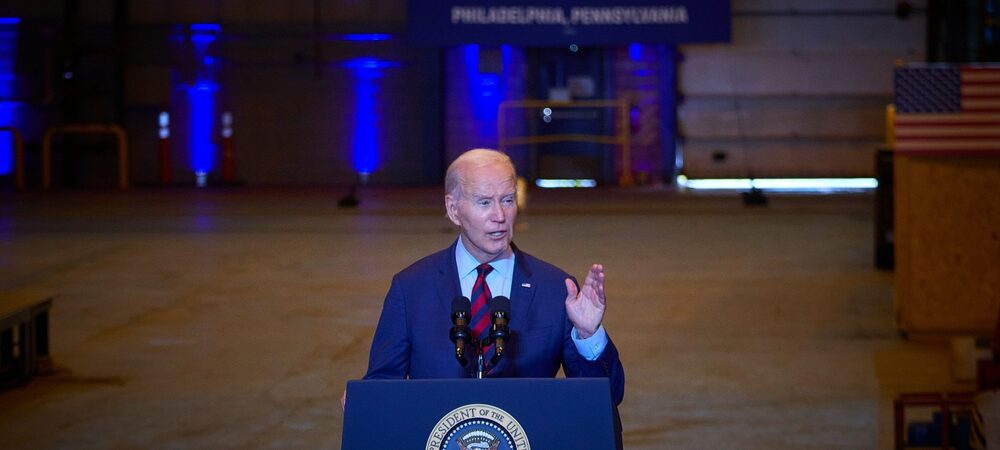

The Biden administration has championed this new era, seeing it as a moment to reinvest in US manufacturing and better counter China’s economic clout. However, there has been blowback, and the chorus of critical voices aimed at US trade policies is large and growing. While much of this criticism is valid, as recent trade policies cast aside effective tools, such as FTAs, too cavalierly, there also have been earnest efforts to address pressing new realities.

To begin with, the administration’s efforts to collaborate with the European Union (EU), resolve existing tensions between the two, and forge new paths on critical issues, such as trade and climate change, stand out and deserve credit. During the Obama administration, negotiations on a transatlantic FTA were simply too ambitious, at least at the time, to get to the finish line. Later, the Trump administration upended the trade relationship with tariffs on steel and aluminum, even as it sought cooperation on addressing China challenges, such as nonmarket excess supply. Now, the Biden administration is focusing on reaching a long-term agreement to eliminate these tariffs and developing a framework for incentivizing trade in lower carbon-intensive goods. This work is critical as a counter to China and to avoid the EU’s pending carbon border adjustment measures applying to US exports in key sectors.

In contrast, the Biden administration’s signature effort in Asia to fill the vacuum left by abandonment of what is now the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) has fallen short. The recently concluded supply chain pillar in the Indo Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) is new, different, and seeks to meet the needs of the times. That said, the commitments in this pillar are soft ones, meaning there are few provisions that parties “shall” do something, and instead many that they “intend to” do something. Administration characterizations that this model is better than the old FTA model ignore the fact that FTA negotiations provide scope to include innovative chapters, including ones on supply chains.

The real challenge for the United States will be pinning down a trade pillar agreement that avoids falling far short of similar provisions in FTAs, such as the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) or the CPTPP. The Biden administration will be hard-pressed to obtain high-ambition commitments in the areas of good regulatory practices, trade facilitation, agriculture, labor, and environment without the leverage of market access commitments that accompany FTA negotiations. Count me skeptical. My own experience as an assistant US trade representative for environment and natural resources some years back suggests that FTA negotiations provide the best leverage for environmental commitments, such as those in the Dominican Republic–Central America FTA and the illegal logging provisions in the Peru FTA.

Digital trade is one area in which concerns are extremely high. The Biden administration’s review of its approach to commitments on cross-border data flows and data localization in trade agreements may make sense to ensure compatibility with regulatory trends in the United States. However, it appears the administration’s pullback in IPEF and WTO negotiations is an overreaction and will have significant implications for one of the top exporting sectors for the United States.

The US-India trade relationship is a test case for this new era. US policies toward India have evolved rapidly on the strategic front, and India’s perceived role in alliances to counter China is a central reason for this. However, the US-India trade relationship is playing catch-up to match breakthroughs on the strategic and defense fronts. While there are plenty of landmines ahead in the bilateral strategic landscape, including diverging self interest in relationships with Russia, the trajectory is likely to continue to be positive. On the trade and commercial front, the direction in the bilateral relationship is also positive, but it has a much lower starting point. The Trade Policy Forum, which wrestles through high-profile trade irritants, and the companion Commercial Dialogue, which helps to bring private sector chief executive officers into the circle, are producing more breakthroughs and expanding the scope of government-to-government collaboration on the economic front. However, Washington and New Delhi need to get more creative in building a bigger trade relationship, and they should start in 2024.

It is unfortunate that an FTA with India is not in the cards so long as the Biden administration continues to view this approach (wrongly, in my view) as archaic and not built for new challenges. Consequently, other forms of negotiation should fill the gap until there is a return to good sense and resumption of FTA negotiations. Early possibilities could include negotiations on India’s beneficiary status under the Generalized System of Preferences program and a critical minerals agreement.

For the moment, it appears a first-term Biden administration’s trade policies will continue to disappoint many experts, including former negotiators, members of Congress on both sides of the aisle, and the exporting private sector, even if some of its innovations bear fruit in the future. One might hope that there already are internal discussions taking place on what a second term might bring in trade policy, including consideration of bringing back some of the old policies while continuing to find new ways to address pressing priorities. It will take a combination of both to redress the harms brought on by globalization and the challenge of China while also innovating to bring climate change to the fore of US trade policy.

Mark Linscott is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center and former assistant US trade representative for South and Central Asia, WTO and multilateral affairs, and environment and natural resources.

To read the full blog post, click here.