In prior posts, I have reviewed the challenges globally on food security flowing from Russiaʼs invasion of Ukraine. These challenges compound the difficulties flowing from climate change problems of extended draughts in various parts of the world and the challenges for countries trying to rebound from the COVID-19 pandemic. See, e.g., May 24, 2022: How severe is the food security challenge?, https://currentthoughtsontrade.com/2022/05/24/how-severe-is-the-food-security-challenge/; May 16, 2022: Wheat prices spike following Indian export ban, https://currentthoughtsontrade.com/2022/05/16/wheatprices-spike-following-indian-export-ban/; May 15, 2022: India bans exports of wheat, complicating efforts to address global food security problems posed by Russiaʼs war in Ukraine,

https://currentthoughtsontrade.com/2022/05/15/india-bans-exports-of-wheat-complicating-exorts-toaddress-global-food-security-problems-posed-by-russias-war-in-ukraine/; April 19, 2022: Recent estimates of global effects from Russian invasion of Ukraine, https://currentthoughtsontrade.com/2022/04/19/recentestimates-of-global-exects-from-russian-invasion-of-ukraine/; March 30, 2022: Food security challenges posed by the Russian invasion of Ukraine,https://currentthoughtsontrade.com/2022/03/30/food-security-challenges-posed-by-the-russian-invasion-ofukraine/.

In prior periods of agricultural shortages and inflationary prices for agricultural goods, there has been significant social unrest particularly in countries where food accounts for a large part of disposable income for people. See Financial Times, ʻPeople are hungryʼ: food crisis starts to bite across Africa, June 23, 2022, https://www.y.com/content/c3336e46-b852-4f10-9716-e0f9645767c4 (“During the 2007-2008 food crisis, which was caused by a spike in energy prices and droughts in crop-producing regions, about 40 countries faced social unrest: More than a third of those countries were on the African continent.”); see also Terence P. Stewart, The Food Crisis: A Survey of Sources and Proposals for Preventing a Global Catastrophe, 2008 (copied in March 30, 2022: Food security challenges posed by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, https://currentthoughtsontrade.com/2022/03/30/foodsecurity-challenges-posed-by-the-russian-invasion-of-ukraine/)(excerpt from the summary copied below).

A recent paper from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization and the World Food Programme identifies countries in danger of starvation or acute hunger in the June – September 2022 time period. FAO, WFP, Hunger Hotspots, FAO-WFP early warnings on acute food insecurity, June to September 2022 Outlook, https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000139904/download/?_ga=2.27484728.588580763.1656342884-1119086152.1656342884. The Executive Summary (page 5 of the report) is copied below.

“The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the World Food Programme (WFP) warn that acute food insecurity is likely to deteriorate further in 20 countries or situations (including two regional clusters) – called hunger hotspots – during the outlook period from June to September 2022.

“Acute food insecurity globally continues to escalate. The recently published 2022 Global Report on Food Crises alerts that 193 million people were facing Crisis or worse (Integrated Food Security Phase Classification [IPC]/Cadre Harmonisé [CH] Phase 3 or above) across 53 countries or territories in 2021. This increase must be interpreted with care, given that it can be attributed to both a worsening acute food insecurity situation and a substantial (22 percent) expansion in the population analysed between 2020 and 2021. In addition, an all-time high of up to 49 million people in 46 countries could now be at risk of falling into famine or famine-like conditions, unless they receive immediate life and livelihoods-saving assistance. This includes 750 000 people already in Catastrophe (IPC/CH Phase 5)

“Ethiopia, Nigeria, South Sudan and Yemen remain at the highest alert level as in the previous edition of this report. In the current report, Afghanistan and Somalia have been added to the list. These countries all have some populations identified or projected to experience starvation or death (Catastrophe, IPC Phase 5) or at risk of deterioration towards catastrophic conditions, and require the most urgent attention.

“In Afghanistan, for the first time since the introduction of IPC in the country in 2011. Catastrophic conditions (IPC Phase 5) are present for 20 000 people in Ghor due to limited humanitarian access during the March to May period. In the outlook period, acute food insecurity is projected to increase by 60 percent year-on-year.

“After projecting 401 000 people facing Catastrophic conditions (IPC Phase 5) in Tigray, Ethiopia, in 2021, only 10 percent of required assistance arrived in the region until March 2022, and local agricultural production – which was 40 percent of the average – was critical for food security and livelihoods. A recent ʻhumanitarian truceʼ remains fragile but has allowed for some convoys to reach the region. The Famine Review Committeeʼs 2021 scenarios of a Risk of Famine for Tigray might remain relevant, unless humanitarian access stabilizes.

“Although no populations were projected to be in Catastrophe (CH Phase 5) in Nigeria in the outlook period, the record-high levels of acute food insecurity are of serious concern. Importantly, the population in Emergency (CH Phase 4) is expected to reach close to 1.2 million people during the peak of the lean season from June to August 2022, including in Adamawa, Borno and Yobe where some local government areas continue to be inaccessible or hard to reach.

ʻIn Somalia, a Risk of Famine has been identified through June 2022, under a scenario where rains are significantly below average, food prices increase further, conflict and displacement increase and humanitarian assistance remains insuxicient – 81 000 people will face Catastrophe (IPC Phase 5) between April and June.

“In South Sudan, a Famine Likely situation, which was present in some areas in 2021, was averted by improved coordination of humanitarian assistance, and hence the projected number of people in Catastrophe (IPC Phase 5) was reduced slightly, to 87 000 between April and July. That said, the situation remains of highest concern.

“In Yemen, the food security situation deteriorated significantly compared to last year, including a strong increase in the number of people in Catastrophe (IPC Phase 5), which are projected to reach 161 000 over the outlook period. There is also a Risk of Famine projected for some areas.

“The Democratic Republic of the Congo, Haiti, the Sahel region, the Sudan and the Syrian Arab Republic remain countries of very high concern, as in the previous edition of this report. In this edition, Kenya is added to the list. This is due to the high number of people in critical food insecurity coupled with worsening drivers expected to further intensify life-threatening conditions. Sri Lanka, West African coastal countries (Benin, Cabo Verde and Guinea), Ukraine and Zimbabwe have been added in the list of hotspot countries compared to the January 2022 edition of this report. Angola, Lebanon, Madagascar and Mozambique remain hunger hotspots.

“Organized violence and conflict remain the primary drivers for acute hunger, with key trends indicating that conflict levels and violence against civilians continued to increase in 2022. Moreover, weather extremes such as tropical storms, flooding and drought remain critical drivers in some regions.

“Ripple effects of the war in Ukraine have been reverberating globally against the backdrop of a gradual and uneven economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, steadily increasing food and energy prices, and deteriorating macroeconomic conditions. Disruptions to the Ukrainian agricultural sector and constrained exports reduce global food supply, further increase global food prices, and finally push up already high levels of domestic food price inflation. Additionally, high fertilizer costs are likely to affect yields and therefore the future availability of food. Adding to the economic instability, civil unrest could emerge in some of the most affected countries in the upcoming months. Finally, humanitarian organizations are seeing sharp cost increases for their operations and reduced global attention risking to translate into increasing funding shortages. (emphasis added)

“Targeted humanitarian action is urgently needed to save lives and livelihoods in the 20 hunger hotspots. Moreover, in six of these hotspots – Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan and Yemen – humanitarian actions are critical to preventing starvation and death. This report provides country-specific recommendations on priorities for emergency response as well as anticipatory action to address existing humanitarian needs and ensure short-term protective interventions before new needs materialize.”

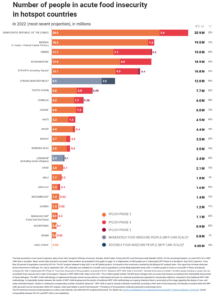

The report at page 12 provides a chart showing the number of people in acute food insecurity in hotspot countries. The page is copied below.

The Financial Times article referenced earlier notes that there have already been signs of social unrest in a number of countries — Chad, Uganda, and Kenya. See Financial Times, ʻPeople are hungryʼ: food crisis starts to bite across Africa, June 23, 2022, https://www.y.com/content/c3336e46-b852-4f10-9716-e0f9645767c4. Similarly, the Economist has flagged social unrest from rising food and energy prices in two recent articles. See The Economist, Costly food and energy are fostering global unrest, June 23, 2022, https://www.economist.com/international/2022/06/23/costly-food-and-energy-are-fostering-global-unrest (“All around the world, inflation is crushing living standards, stoking fury and fostering turmoil. Vladimir Putinʼs invasion of Ukraine has sent prices of food and fuel soaring. Many governments would like to cushion the blow. But, having borrowed heavily during the pandemic and with interest rates rising, many are unable to do so. All this is aggravating pre-existing tensions in many countries and making unrest more likely, says Steve Killelea of the Institute for Economics and Peace (iep), an Australian think-tank.”); The Economist, A wave of unrest is coming. Hereʼs how to avert some of it, June 23, 2022, https://www.economist.com/leaders/2022/06/23/a-wave-of-unrest-is-coming-heres-how-to-avert-some-of-it (“Jesus said that man does not live by bread alone. Nonetheless, its scarcity makes people furious. The last time the world suffered a food-price shock like todayʼs, it helped set ox the Arab spring, a wave of uprisings that ousted four presidents and led to horrific civil wars in Syria and Libya. Unfortunately, Vladimir Putinʼs invasion of Ukraine has upended the markets for grain and energy once again. And so unrest is inevitable this year, too.”). The Economist, in the first referenced article, forecasts the likelihood of increase in serious outbreaks of unrest over the next twelve months. Much of Africa, various countries in Asia and the Middle East and parts of Central and South America show increases from 25% to 100% over the prior 12 months. The article also reviews challenges in Turkey, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tunisia, Peru, Uganda, Turkmenistan and South Africa.

Major countries and multilateral organizations have been taking actions to try to address some of the challenges presented from the price inflation on food, fertilizer and energy. Some countries that are able are providing assistance to their people with tax reductions or monetary grants. See, e.g., Reuters, Malaysia plans record $18 billion subsidy spend in inflation fight, June 25, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/malaysia-plans-record-18-bln-subsidy-spend-inflation-fight-2022-06-25/ (“Malaysia is projected to spend 51 billion ringgit on consumer subsidies including for fuel, electricity, and food, assuming that commodity market prices remain at current levels, Finance Minister Tengku Zafrul Aziz said in a statement. The government will also distribute 11.7 billion ringgit in cash aid, and 14.6 billion ringgit in other subsidies, he said.”). Other countries provide economic assistance to those in need in other countries. See, e.g., European Commission, Food security: EU to step up its support to African, Caribbean and Pacific countries in response to Russiaʼs invasion of Ukraine, June 23, 2022, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_22_3889

Prices for wheat and sunflower oil have spiked since the war as Ukraineʼs large volumes that are normally exported have been trapped in Ukraine by Russiaʼs blockade of Black Sea ports, destruction of grain and sunflower seed silos by Russian missiles, by the they of Ukrainian product by the Russians and limitations on Ukrainian farmers being able to work their land during the war. See, e.g., NPR, Russia has blocked 20 million tons of grain from being exported from Ukraine, June 3, 2022, https://www.npr.org/2022/06/03/1102990029/russia-has-blocked-20-million-tons-of-grain-from-beingexported-from-ukraine; Center for Strategic & International Studies, Spotlight on Damage to Ukraineʼs Agricultural Infrastructure since Russiaʼs Invasion, June 15, 2022, https://www.csis.org/analysis/spotlight-damage-ukraines-agricultural-infrastructure-russias-invasion (“Russia is taking advantage of the transportation bottlenecks caused by port blockades to target Ukraineʼs food storage facilities. According to Ukraineʼs ministry of defense, Russian forces have attacked (https://observers.france24.com/en/europe/20220506-russian-attacks-on-farms-and-silos-deliberately-tryingto-destroy-the-ukrainian-economy) grain silos across the country and stolen an estimated 400,000-500,000 metric tons of grain (https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-health-middle-eastf980a51dab3412aba611277821e2822b) from occupied regions to increase Russian competitive advantage in the export market (https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/05/05/ukraine-grain-they-russia-hungerwar/).”).

Efforts have been being made by the UN, by Turkey and others to get Russia to stop its blockade of Ukrainian ports to permit the export of grain and other agriculture products. See, e.g., Reuters, Russia, Turkey to pursue talks on Ukraine grain exports, June 23, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/russia-turkey-agree-moreconsultations-grain-exports-ukraine 2022-06-22/ (https://www.reuters.com/world/russia-turkey-agree-moreconsultations-grain-exports-ukraine-2022-06-22/) (“Ukraine is one of the top global wheat suppliers, but shipments have been halted by Russiaʼs invasion, causing global food shortages. The United Nations has appealed to both sides, as well as maritime neighbour Turkey, to agree to a corridor.”)

At the same time, the European Union and United States have been working to help Ukraine export wheat and other agricultural products by alternative routes, though the volume that can be so moved is only a small percentage of what Ukraine normally exports. See, e.g., European Commission, Commission to establish Solidarity Lanes to help Ukraine export agricultural goods, 12 May 2022, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_3002; Politico, Biden races against time to unlock Ukraineʼs trapped grain, June 17, 2022, https://www.politico.com/news/2022/06/17/biden-ukrainetrapped-grain-00040640

Multilateral organizations like the World Bank, IMF and World Trade Organization have been offering assistance within their zones of competence. For example, the World Bank has a variety of programs that have been started or utilized to help with the growing food insecurity. See World Bank, Food Security Update | Rising Food Insecurity in 2022, June 23, 2022, https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/agriculture/brief/foodsecurity-update# (lists 14 projects including “The $2.3 billion Food Systems Resilience Program for Eastern and Southern Africa (https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/06/21/world-bank-approves-2-3-billion-programto-address-escalating-food-insecurity-in-eastern-and-southern-africa), approved on June 21, 2022, helps countries in Eastern and Southern Africa increase the resilience of the regionʼs food systems and ability to tackle growing food insecurity.”). The World Bankʼs update on food insecurity is embedded below.

The WTO during the 12th Ministerial Conference which concluded on June 17, 2022 did address food security concerns both by agreeing not to block exports to the World Food Programme and by agreeing to transparency on actions taken and exorts to minimize use of export restraints on agricultural products. See June 17, 2022: WTOʼs 12th Ministerial Conference — some successes after a difficult five plus days,https://currentthoughtsontrade.com/2022/06/17/wtos-12th-ministerial-conference-some-successes-ayer-adixicult-five-plus-days/.

In addition, the U.S., European Union and other allies coordinating actions to help Ukraine and hold Russia accountable, have been working to address access to food products, energy products and to increase availability of fertilizers. These actions have been announced by major players unilaterally as well as through various groupings, including the current G-7 meeting in Germany, U.S.-chaired Global Food Security Ministerial Meeting, and the recently concluded Summit of the Americas Agriculture Producers Declaration. See, e.g., The White House, Summit of the Americas Agriculture Producers Declaration, June 13, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/06/13/summit-of-americasagriculture-producers-declaration/; U.S. Department of State, Chairʼs Statement for Global Food Security — call to Action, June 24, 2022, https://www.state.gov/chairsstatement-roadmap-for-global-food-security-call-to-action-2/; European Commission, Commission acts for global food security and for supporting EU farmers and consumers, 23 March 2022, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_1963; U.S. Department of State, Secretary Antony J. Blinken During the Uniting for Global Food Security Conference, June 24, 2022, https://www.state.gov/secretary-antony-j-blinken-during-the-uniting-for-global-food-security-conference/. These four documents are embedded below.

A few thoughts

The major efforts underway by various countries to reduce the global effect of the Russian war on food security are extensive and will have positive effects, some immediately, others over time (e.g., increasing production of fertilizers or improving efficiencies of fertilizers). However, for the poorest countries and those reliant on food imports from Ukraine and Russia, the internal pressures will continue to mount as limited financial resources and high food and energy prices push more and more people into food insecurity situations of increased severity. Social unrest in a number of countries is likely.

While Russia has exacerbated the food insecurity by its actions on Ukraineʼs agricultural products and by other actions restricting its own exports (when sanctions do not cover agricultural goods or fertilizers) and has the ability to end the challenges it has created, it seems highly unlikely that any serious progress will be made in getting Ukrainian agricultural goods out through Black Sea ports while hostilities continue. EU and U.S. efforts are helping some but are not perceived to be a viable short-term solution to moving Ukrainian goods to export markets at affordable prices.

Some short-term steps the private sector can take to help alleviate the damage to at-risk countries is to increase funding to the World Food Programme (its June report cited earlier is this post reflect that with higher prices and challenges in getting funding, the WFP is being forced to reduce assistance in various countries). While most funding for WFP comes from governments, the private sector can contribute and should actively participate. Obviously, there is need for more funding by governments as well, but the multiple crises at least make it questionable how much more governments will do in fact in 2022.

Moreover, with the large number of low and middle-income countries facing potential debt crises, there is a need for at least selective debt relief where the challenges faced flow simply from the rapid increase in inflation.

None of the proposals for action by those looking to lessen the pressures on global markets has involved increasing the percent of the worldʼs grain that goes to human consumption during the current crisis. See The Economist, Most of the worldʼs grain is not eaten by humans, June 23, 2022, https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2022/06/23/most-of-the-worlds-grain-is-not-eaten-by-humans. Presumably the challenges flow from the large percentage of grains that are fed to animals and the reduction in the worldʼs pasturelands which make alternative feeding of livestock less likely to increase in the short term. A small percentage (10%) of grains goes to biofuels and would be unlikely to be shifted in the short term as the use of grains in biofuels reduces the volume of petroleum products otherwise needed.

In challenging times, it is important for key countries to step forward and show leadership. There has been extensive leadership shown by the U.S., the EU and many of the other countries involved in supporting Ukraine and holding Russia to account for its unprovoked war with Ukraine. Continued coordination and adoption of bold actions by those currently engaged and an expanded group of willing participants will be needed to reduced the damage to low- and middle-income countries and limit the amount of social unrest that will yet unfold in 2022 and 2023.

Terence Stewart, former Managing Partner, Law Offices of Stewart and Stewart, and author of the blog, Current Thoughts on Trade.

To read the full commentary from Current Thoughts on Trade, please click here.