Taxes aren’t quite the certainty they once seemed to Benjamin Franklin.

On Monday, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development said the new global rules it is developing could add $100 billion a year to multinational companies’ tax bills. That might sound like an unappealing prospect for investors, but the OECD painted a bleaker alternative: a chaos of digital taxes and tariffs that could cut global output by 1%. This outcome would itself hit corporate earnings, even if the new levies didn’t.

The estimates were prepared for this month’s meeting of G20 finance ministers. The figures can be debated, but the basic trade-off is plausible: Politicians can agree to global tax changes or risk a trade war. Progress will have to wait until after November’s U.S. election, given that Washington’s participation is crucial. Unhelpfully, there isn’t a clear indication of how either potential administration might proceed.

OECD officials had originally hoped for a deal by the end of this year, but are now aiming for summer 2021. If the negotiations fail, France and a number of other nations have committed to applying new digital service taxes, or DSTs, possibly prompting retaliatory U.S. tariffs. The resulting patchwork would “inevitably result in double taxation and even more uncertainty for businesses,” says Sarah Shive of the Information Technology Industry Council, a trade association.

Many countries, particularly in Europe, have long wanted U.S. tech companies to pay more corporate tax locally on services provided to their citizens. Silicon Valley typically pays low tax rates outside the U.S. as current rules focus on the location of plants, employees and other assets rather than sales. After agreeing to domestic tax changes in 2017, Washington showed renewed interest in a global overhaul, but seemed to get cold feet last December and suggested that the new rules be optional for U.S. companies.

That might sound like a nonstarter—who would opt in to higher taxes?—but big tech companies have said they wouldn’t mind paying more if it gave them certainty about their future bills. The choice to opt-in would give them a chance to follow through, though it isn’t clear that the countries proposing DSTs are willing to take them at their word and agree to an optional global overhaul.

Negotiations have settled on two revisions: changing taxing rights so that they don’t require a physical presence, and setting a minimum global tax.

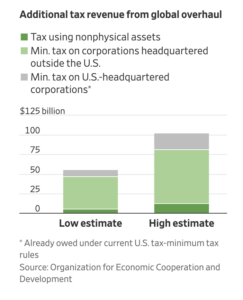

The first change would reallocate about $100 billion of taxes from mostly low-tax jurisdictions to other countries with only a small overall increase, says the OECD. The minimum-tax provision is similar to the one introduced by the U.S. government in 2017, which was forecast to add $21 billion a year to U.S. multinationals’ tax bills by 2027. Creating a similar global rule would collect a further $80 billion from big multinationals based outside the U.S.

Companies might be willing to pay more for tax certainty, but they are unlikely to get it any time soon.

Rochelle Toplensky is a Heard on the Street columnist based in London, where she covers European banks and EU antitrust.

To read the original blog, click here.