Ask Zhu Kaiyu about his factory, and he can rattle off a series of statistics meant to impress: 15,000 square meters, 800 employees, 300 machines, 5 million articles of clothing sold per year. Zhu opened his factory for knitted apparel in Dongguan, in China’s Guangdong province, in 2002. He’s proud to be the trusted manufacturing partner for foreign companies like Full Beauty Brands, the owner of several American brands for plus-size men’s and women’s apparel. In a normal year, he says, 30% of his revenue comes from overseas.

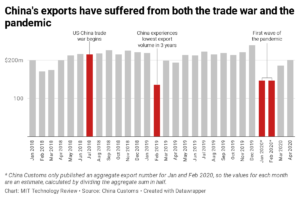

But in 2018, things stopped being normal. Across his industry, the US-China trade war had begun to strain apparel makers, one of China’s manufacturing sectors with the largest reliance on export sales. Orders that had been placed and made in advance were being delayed up to three months for shipping, hitting Zhu’s profits and clogging up his storage space with unsaleable inventory.

Then, before his business had fully recovered, covid-19 ripped through the world. Exports tanked, saddling Zhu with a stream of order cancellations worth an estimated $4 to $5 million. Domestic sales also suffered as physical stores shuttered under pandemic control restrictions. “The impact could’ve been huge,” he says. “My factory is really big; I have so many workers to support.”

But Zhu fortunately had another sales channel. In 2018, Pinduoduo, an e-commerce giant targeted at consumers in China’s smaller cities, launched an initiative to connect manufacturers with the domestic market. Under a so-called “consumer-to-manufacturer,” or C2M, model, the platform began using its massive pools of data and AI algorithms to help Chinese manufacturers predict consumer preferences and develop brands specifically for a domestic audience.

Pinduoduo told manufacturers not only how to customize their products—down to the wash of a jean or the length of a sock. It also advised them on how to redesign their packaging, how to set their prices, and how to market their goods online. In this way, manufacturers could improve the efficiency of their production, which in turn made the products cheaper for consumers. And platforms could monetize new users with advertising. This helped both the platform and manufacturers alike tap into a rapidly growing middle-class consumer base. Whereas upper-class consumers care more about international brands, this newer wave of consumers care more about quality products at lower prices.

When the pandemic hit, Pinduoduo quickly expanded its initiative. It added new incentives for affected manufacturers to join its platform, welcoming them to adopt its live-streaming service (link in Chinese) and holding promotional sales events. And so, Zhu joined in with his own brand—水中君 (shui zhong jun), King of the Water—to recover his lost international revenue. He followed C2M guidance and set up a live-streaming channel. As of May, he says, he can now sell up to 25,000 items of clothing via livestream within a few hours—up from an average of 1,000 items per day.

The C2M model originally began as part of a broader push by such giants to modernize the manufacturing industry and attract more consumers onto their platforms. But the trend has accelerated and taken on new meaning since the trade war and the prolonged pandemic. As China’s access to international markets has grown more unreliable—with a possible trade fight renewal looming on the horizon—the country has increasingly sought to ramp up domestic consumption in an effort to stave off a greater economic recession.

“The problem is China is losing [overseas] demand,” says Derek Scissors, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, where he researches trade policy and US-China relations. “You want to replace it with Chinese demand.”

As well as Pinduoduo, other Chinese e-commerce giants, including Alibaba-owned Taobao and JD, are now offering C2M services. Since the start of this year, all three have set new goals for expanding their C2M initiatives. Pinduoduo, which helped launch 106 manufacturer-owned brands in 2019, aims to establish 1,000 more. It also signed a strategic partnership in April with the government of Dongguan, where Zhu’s factory is based, one of China’s largest manufacturing hubs.

Taobao, likewise, has committed to bringing at least 100 million RMB ($14 million) to 1,000 manufacturers each, distributed across 10 factory clusters, within the next three years. In March, it launched a new app called Taobao Deals to showcase the lower-price products designed through its C2M partnerships. JD says it will recruit partners across more than 100 industrial belts. In April, it also launched a “Export to Domestic” initiative through its new app Jingxi to let manufacturers open new stores on its platform for free and tap into its marketing, logistics, and delivery services.

In 2018, the C2M model generated roughly 17.52 billion RMB ($2.5 billion) in total sales, according to market research firm iResearch. It’s estimated to grow to 42 billion RMB ($5.9 billion) by 2022.

As the partnerships have produced promising results, manufacturers have also doubled down on their domestic brand strategies. Chen Zhuoyue, the owner of a toy manufacturing company based in Chenghai, Guangdong, joined JD’s C2M program in 2018. After JD helped him customize his products and develop a new pricing strategy, the platform quickly grew to account for 50% of his domestic sales. When the pandemic hit and his exports sharply declined from 30% to less than 5% of his revenue, he took it as a sign to open up two new JD stores and launch more domestic brands.

It’s not that Chen will stop working with foreign brands. “As a businessman, I’m always thinking about how to expand into more markets,” he says. If exports were to return back to normal and his long-term foreign collaborators came knocking on his door, he would gladly continue fulfilling their orders. At the same time, now that he’s launched his own brand, he sees it as an important source of growth and stability. “My plan is to expand our domestic presence,” he says. “This year I want to increase our investment in this area.”

It’s not clear whether domestic markets alone will be able to compensate for China’s variable access to international markets over the long run. On one hand, the country’s middle class has rapidly increased their spending power and is expected to grow to a market size of 1,008 billion RMB ($141 million) by 2022, according to iResearch. On the other, even before the pandemic, the manufacturing industry was already struggling with too much supply, says Scissors, and it relied on the US and other overseas markets to “dump their manufacturing excess,” he says. As a result, he’s unconvinced that a new model like C2M would resolve such deeply-entrenched macroeconomic issues. If anything, he sees C2M instead as a savvy push from e-commerce giants to grow their own profits.

Nonetheless, China’s rhetoric has continued to emphasize a greater domestic focus over time, as the country seeks to build up greater economic and technological self-sufficiency. For individual manufacturers like Zhu, the C2M model has certainly provided him a greater sense of resilience. Should more unpredictable external factors come his way, like another trade war, he would just continue to invest in his C2M partnership with Pinduoduo, he says: “We would improve our products, our R&D, and our production. We would further establish our brands.”

To view the original blog post, click here.