The IMF’s October 2020 WEO asserts, incorrectly, that the pandemic has led global current account imbalances to shrink.*

A reduction in imbalances of course could have been the outcome of the pandemic. Less trade, all else equal, should mean smaller deficits and smaller surpluses (that is the math of a symmetric fall in trade).

But it is not what is in the data.

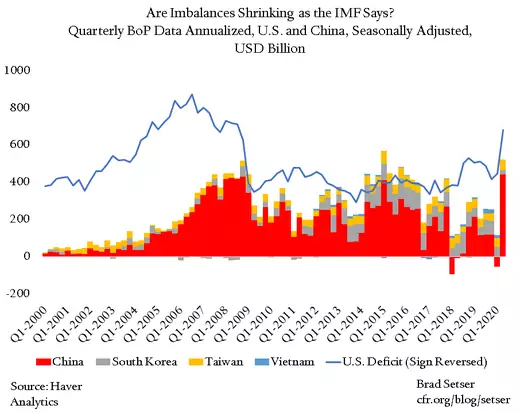

Rather, the global data shows a significant increase in both the U.S. external deficit and China’s external surplus in the second quarter.

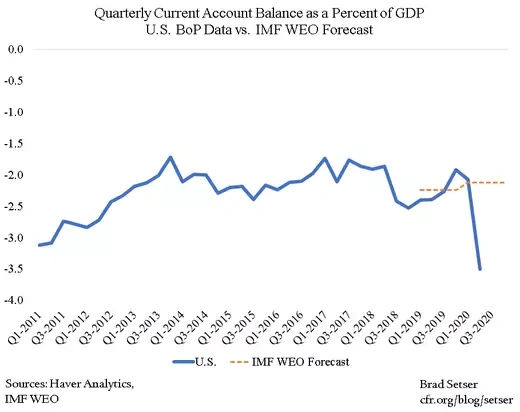

That makes the IMF’s forecast that the U.S. external deficit will shrink both in dollar terms and as a share of U.S. GDP in 2020 (see both chapter 1 and the data tables in the statistical appendix [PDF]) all the more maddening.

The IMF, somehow got the most important part of any global current account forecast wrong (see the General Theorist for an exploration of the IMF’s possible methodology, the WEO production cycle may have fixed the forecast before the U.S. second quarter data was formally released).

Nothing matters more to the global flow of funds than the U.S. deficit, as the United States is both the world’s largest economy and the necessary counterpart to a rise in the surplus of many surplus countries. So, when the IMF has the U.S. current account deficit falling to 2.1 percent of GDP it matters for the world, not just the United States.

In practice, the U.S. external deficit in the second quarter was 3.5 percent of U.S. GDP. The deficit in the third quarter is likely to be bigger.

The IMF’s forecast for the world’s largest economy and the largest single source of balance of payments imbalances is thus likely to be off by more than a percentage point of GDP.

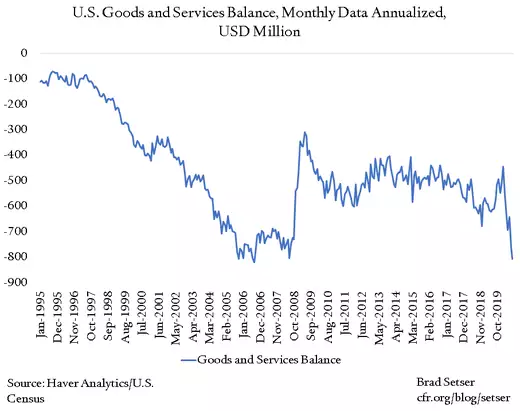

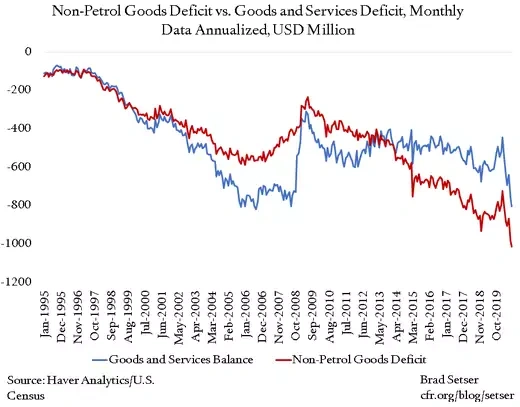

All it takes to know the IMF’s forecast is off is a quick glance at the monthly U.S. trade data, as the U.S. trade deficit and the broader current account deficit blew out in the second quarter and are poised to widen even further in the third quarter. The August deficit, annualized, is over $800 billion—more than $225 billion greater than the 2019 annual deficit of around $575 billion.

The reasons for the blowout in the U.S. deficit are by now well known. There has been a shift in the composition of U.S. household demand away from (mostly domestically-produced) services and toward durable goods (mostly imported). The stimulus measures passed back in a brief moment of bipartisan clarity this spring supported U.S. household demand. The dollar remains relatively strong.**

Still, the gap between the performance of U.S. imports and U.S. exports is extremely large (explained, in part, by the fact that aircraft and vacations that require taking a flight are a major part of the traditional U.S. export base).

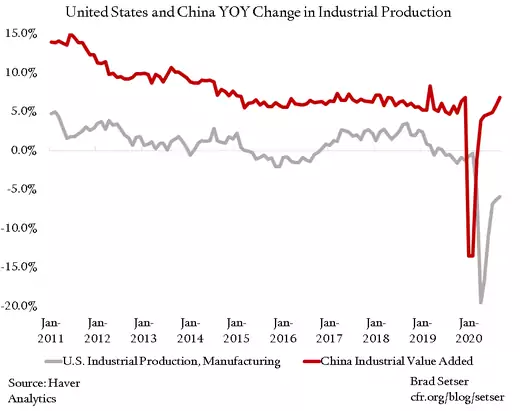

There equally has been the gap between the recovery in U.S. consumption of durable goods and U.S. manufacturing output. The stimulus, at least so far, has not done all that much to stimulate increased U.S. production of manufactures.

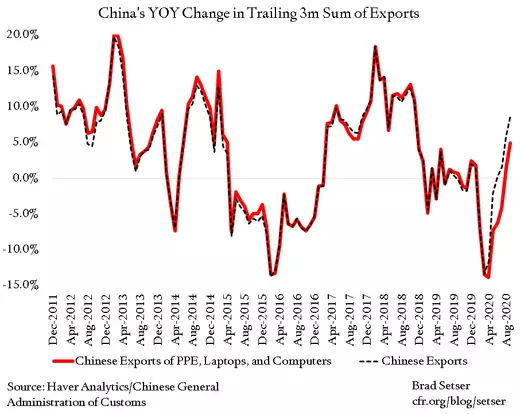

The reasons for China’s strong export performance are by now also well known (see Dan Alpert on Twitter). It had the broad manufacturing production base needed to scale up output of personal protective equipment (PPE). President Trump’s trade war largely left out laptops and cellphones, so global supply chains for the kind of goods needed to work from home are still Sino-centric. And, well, the yuan has been quite weak (it was close to a ten year low against the dollar during the first part of the year), which has supported Chinese exports of all kinds—in the third quarter, Chinese exports of goods other than medical textiles and computers (including tablets and laptops) were up 5 percent year-over-year (YOY).

As a result, China has posted a current account surplus of over $100 billion in the second quarter (over $400 billion annualized) and is poised to post another similar surplus in the third quarter. Even with the first quarter deficit, the surplus for the year should check in at close to $300 billion—far more than the $193 billion (1.3 percent of China’s GDP) the IMF forecast in the WEO.

To put it bluntly, the second quarter balance of payments data—which will be reinforced when the data for the third quarter emerges—shows biggest swing in transpacific imbalances since the global financial crisis.

Now it is possible that these swings are all temporary and will naturally fade next year. That is certainly the best outcome for the world. My guess is that it will not prove to be politically sustainable for the U.S. stimulus to do more to support Chinese production than U.S. production.***

Right now, Chinese industrial production is up 7 percent YOY, while U.S. manufacturing production is down 6 percent YOY—the biggest gap in relative performance in a very long time.

But it is possible that the swings will not be temporary. China has not done much to support its own household income—arguably because it has not needed to do so in a world where its exports are doing so well. And given the ongoing reluctance from Chinese policymakers toward broad-based stimulus, China’s fiscal policy response to COVID-19 may be much more tepid than the fiscal response of China’s largest trading partners. Combine that with a still-managed exchange rate that is still weak against both the dollar and the euro even with the modest appreciation in the third quarter and the PBOC’s desire for “basic stability” in the exchange rate and you have the recipe, at least in theory, for a sustained widening of trade imbalances.****

Given that balance of payments surveillance remains at the heart of the IMF’s mandate, I would think that risk warrants a bit of attention and analysis.

The 2009 crisis, thanks to the combination of China’s stimulus and the lagged impact of its 2007-2008 appreciation of the yuan (initially against the dollar, which translated into a broader appreciation when the dollar rallied a bit against the euro) led to a reduction in trade imbalances.

Without some policy corrections, I fear that there is a real risk that COVID-19 will lead to a sustained, rather than temporary, re-widening of imbalances.

*/ I make more use of the data tables at the back of the WEO than most—so errors in those tables bother me more than most. The 2020 data will be corrected in the spring WEO. But that is a long time to wait for plausible, globally consistent numbers.

**/ When looking at the impact of trade on the U.S. economy, I typically focus on the non-petrol goods deficit as that clearly shows the impact of the dollar’s 2014 appreciation—and the dynamics around the U.S. oil sector and other traded goods sectors are very different. And services are not accurately estimated in the monthly data, apart from tourism. But for forecasting the current account balance, the goods and services balance is the most relevant high frequency indicator.

***/ The Economist has done several columns on this topic. See this “Chaguan” column, and this “Free Exchange” column.

****/ The ongoing management of China’s exchange rate is not seriously debated. The precise mechanics of that management are still a bit of a mystery. The PBOC’s headline reserves has not moved at all for some time, but China’s state banks have added $125 billion to their foreign assets over the last six months. See Matt Klein in Barron’s

Creative Commons: Some rights reserved.

Brad W. Setser is the Steven A. Tananbaum senior fellow for international economics at the Council on Foreign Relations.

To read the original blog, click here.