Joe Biden has promised to put the United States on an “irreversible” path to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 while creating millions of well-paying jobs. His Plan for a Clean Energy Revolution and Environmental Justice includes proposals for 100% carbon-free electricity by 2035, $1.7 trillion in green investments over the next ten years and a pledge to devote 40% of these investments to disadvantaged communities.

His plan also includes a carbon border adjustment (CBA) proposal – a pledge to “impose carbon adjustment fees or quotas on carbon-intensive goods from countries that are failing to meet their climate and environmental obligations”. For the European Union, this is a development of great interest in view of the potential joint development of CBA measures. The European Commission has said these could be part of a “transatlantic green trade agenda,” that it will propose in mid-2021.

Here, we discuss some of the main considerations for the introduction of a US CBA.

In the EU, the CBA is generally discussed in relation to the strengthening of carbon pricing schemes. Is this the case for the US also?

No, Joe Biden has actually never pledged to introduce a federal carbon pricing scheme.

The consensus among economists is that this would be the best way to go, but domestic carbon pricing seems still to be politically unviable in the US.

Carbon pricing in the US has so far only been introduced at state level (Figure 1). Of state schemes, the two largest schemes are California’s cap-and-trade system and the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) covering 11 north-eastern states (Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont and Virginia. Pennsylvania is considering joining RGGI).

The Californian system covers industry, power, transport and buildings, amounting to approximately 85% of California’s greenhouse gas emissions. The carbon price currently is around $18/tonne. California is also home to the world’s only CBA. This applies exclusively to the Californian power market, and makes electricity importers liable for the emissions associated with electricity generated by states outside of California.

The RGGI sets a regional cap on emissions from power generation. The programme began in 2009 and the price of carbon is around $6/tonne.

Oregon is considering a cap-and-trade system, with a preliminary start date of 2022. Washington state has made several attempts to implement a form of carbon trading, with the process still in a legal battle.

Without the implementation of nationwide carbon taxation, President Biden is expected to use environmental regulations and targeted investment to speed up US decarbonisation. This is the factor underpinning Biden’s proposal to introduce CBA measures, as environmental regulations represent an implicit carbon price. Nevertheless, implementing a CBA in the absence of a federal carbon price will be a major challenge because environmental regulations impose widely divergent compliance costs per ton of carbon on emitters, based on their individual marginal abatement cost curves. An average compliance cost for producers in a sector, or for all producers in the US, could theoretically be calculated, but it would offer insufficient protection for some (those with higher-than-average marginal abatement costs) while over-protecting others (those with very low marginal abatement costs). With an explicit carbon price, this problem does not arise.

The situation in the US is further complicated because while all producers would be subject to federal non-price climate policies (environmental regulations), others are also subject to an explicit carbon price at the subnational level (for example, Californian industry).

In short, developing a CBA that reflects and adjusts for the carbon costs borne by US producers means balancing a wide range of geographical, sectoral and facility-by-facility differences. Approximations are of course conceivable, but might entail the risk of treating foreign producers less favourably than at least some US producers, which could go against World Trade Organisation rules.

Is this the first discussion in the US of CBA measures?

No. Since the late 2000s, a series of bills have been put forward in the US containing CBA proposals alongside proposals for federal cap-and-trade or carbon tax systems. The US climate debate has long been influenced by a belief that climate policy inevitably results in a loss of competitiveness and jobs. A CBA has typically been viewed in the US as a tool for protecting domestic industry from foreign competition once a carbon price has been implemented. Typically, bills have proposed that domestic importers of foreign goods would surrender emissions allowances equal to the carbon content of the goods they import.

Some bills have sought to expand the scope of product coverage to consumer goods. Others have led to debate on issues such as the criteria for exempting countries and whether the President or Congress should decide on exemptions, and how CBA measures should link with other tools designed to protect competitiveness, including free allowances and how tariff levels should be set.

Among more recent episodes, in 2017, a group of Republicans proposed nationwide revenue-neutral carbon taxation in the US, which was to be accompanied by a CBA. The plan suggested introducing carbon taxation at $40/tonne, increasing steadily and predictably over time. The CBA element would comprise carbon rebates for exports to countries without comparable carbon pricing systems, while imports from those same countries would face fees depending on their carbon content.

In January 2019, bipartisan legislation was introduced to price carbon in a revenue-neutral manner. CBA measures were also included, with both rebates for exports and taxes for imports. In fact, of ten carbon-pricing bills introduced during the 116th session of Congress (2019-2021), all contained a CBA.

These experiences show that bipartisan support may exist in the US for carbon taxation with a CBA, with the right political framing.

Which countries would be most exposed to US introduction of CBA measures?

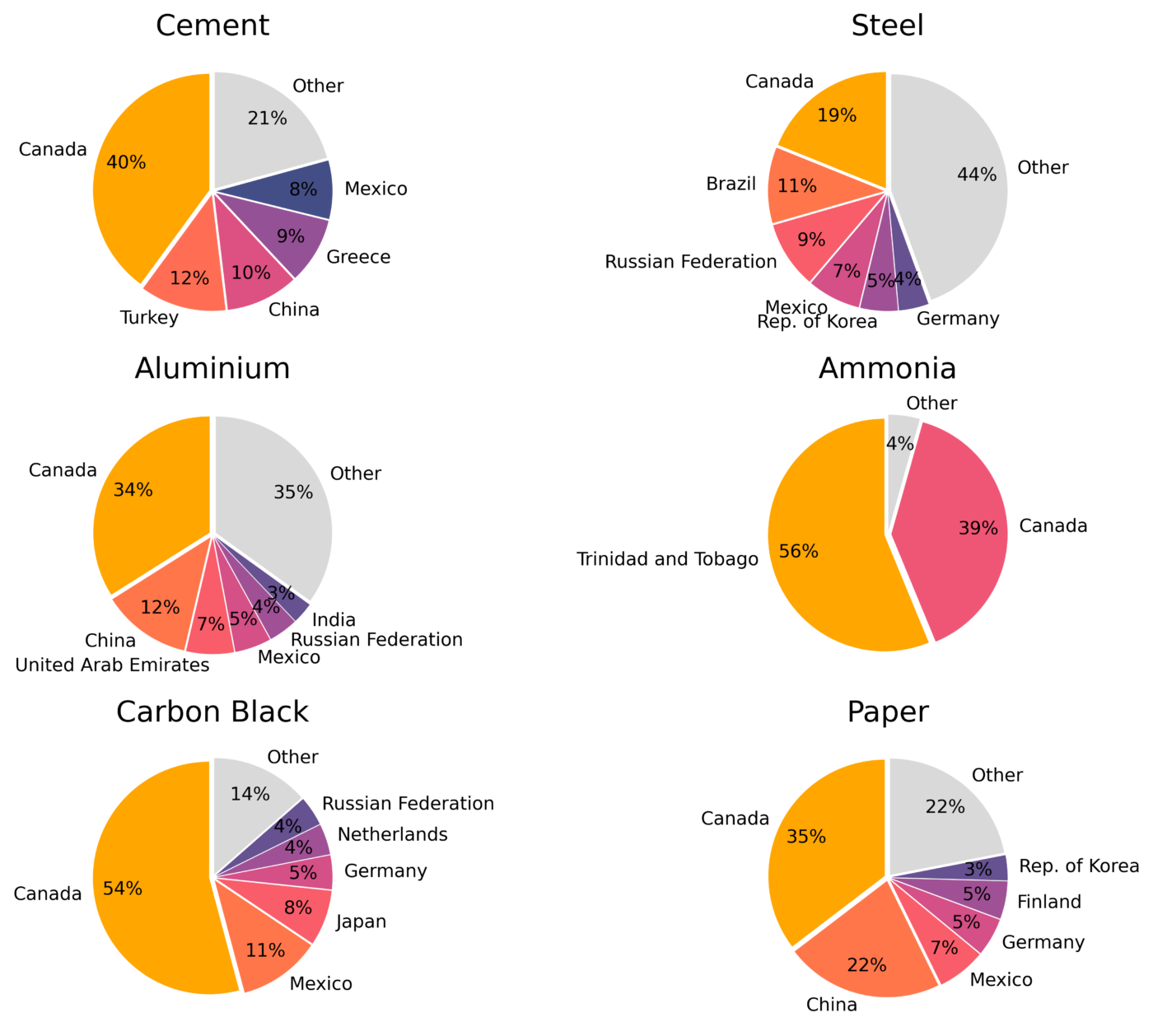

Regardless of design, CBA proposals on both sides of the Atlantic tend to focus on a few emissions-intensive and trade-intensive sectors (Figure 2). These account for a significant share of economies’ emissions and tend to lend themselves to easier calculation of carbon emissions than more complex manufactured goods.

Figure 2 shows where US imports of six such commodities come from, indicating which countries are most likely to be affected by the introduction of a CBA.

Note that certain countries, such as Canada, could argue for CBA exemption, because of domestic carbon taxation. Other countries might be exempted because of their developing economy status.

Does President Biden have the powers to introduce a CBA?

Yes, he has two options at his disposal for passing trade policy related measures: via the legislative branch (Congress) or the executive branch (executive orders).

The standard way for President Biden to pass CBA measures would be through Congressional legislation, as US trade policy requires legislation from Congress on the basis of the Commerce Clause of the US Constitution (Section 8).

However, the Senate is now split, with Vice President Kamala Harris able to cast the deciding vote. Relying on such a narrow Senate majority will likely not be enough for President Biden to pass any comprehensive package containing a CBA. As with previous attempts on climate legislation, any new initiative might fall victim to filibustering by opposing lawmakers.

Moreover, history tells us that the support of all Democratic senators for Biden’s plans should not be taken for granted. Not only would Biden need to secure the votes of at least moderate Republicans (to avoid filibustering delays), he would probably need additional Republicans to compensate for losing a few Democratic senators.

Given the history of bipartisan support in principle for a CBA this might be possible, especially if a bill on CBA is not accompanied by domestic carbon taxation.

Without such support, President Biden’s alternative route would be via executive order, though this could expose him to criticism – Democrats criticised the use of executive orders by President Trump. Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 gives the President the authority to “adjust the imports” of any product that “threatens to impair the national security” of the US. President Trump used Section 232 to pass tariffs on steel and aluminium.

Section 232 should be used when American national security is under threat. . An argument along these lines would have to be made for President Biden to pass CBA by this executive order.

Alternatively, Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 authorises a president to impose tariffs on countries that engage in acts that are “unjustifiable” or “unreasonable” and burden US commerce. Were Biden to implement stricter carbon emission controls within the US, Section 301 could be used on the basis that other countries’ carbon-intensive imports undermine the development of low-carbon American industries. This would be much the same argument as is put forward in the EU, where advocates of a CBA see it as necessary for facilitating decarbonisation within the ETS while ensuring a level playing field.

It is useful to note that from the perspective of WTO law, it does not matter what domestic process was applied, as long as the practical outcome does not violate the US’s international obligations. And the US might well justify the introduction of CBA measures by referring to WTO environmental exceptions, which permit measures “necessary to protect human, animal or plant life or health,” if they are not applied in an arbitrary or discriminatory manner.

In summary, the introduction of CBA measures is unlikely to be the most difficult aspect of the implementation of President Biden’s climate plan. More significant obstacles might emerge over measures to force emissions reductions domestically.

The authors are grateful to Michael A. Mehling (Deputy Director of the MIT Centre for Energy and Environmental Policy Research) and to Robert C. Stowe (Executive Director of the Harvard Environmental Economics Program) for their insightful comments.

To read the full blog post by the Bruegel Blog, please click here.