Given the centrality of trade policy to President Trump’s time in office and re‐election campaign, much has been written about the successes and (more often) failures of the President’s tariffs and resulting trade conflicts, which began in 2018 and accelerated in 2019. The Wall Street Journal today, for example, assesses the President’s “unfinished” trade plans by looking at their effect on manufacturing jobs and economic growth. Numerous other reports — several of which I summarized in a recent article — take a similarly narrow approach when determining who “won the trade war.”

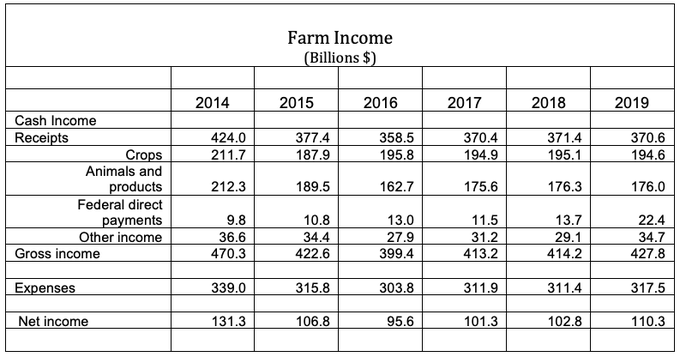

Although such analyses helpfully show some of the ways the President’s trade policies have been ineffective or harmful, they ignore a critical part of the last four years of Trump Trade Wars (and any other period of U.S. trade policy): the political dysfunction that such protectionism always breeds. In the current case, there’s likely no bigger example of this dysfunction than the billions of dollars in new federal subsidies that the Trump administration has provided — with essentially no congressional oversight — since 2018 to politically‐important American farmers who were harmed by (totally expected) foreign retaliation against U.S. agriculture exports. AAF’s Doug Holtz‐Eakin today details just how dependent on the government these farmers have become, showing that well over 100 percent of the increase in U.S. farmers’ net income between 2017 and 2019 ($9 billion) came from subsidies — “federal direct payments” — tied to Trump’s tariffs ($10.9 billion):

According to Politico, direct farm aid in 2020 is scheduled to hit $32 billion — “an all‐time high, with potentially far more funding still to come… amounting to about two‐thirds of the cost of the entire Department of Housing and Urban Development and more than the Agriculture Department’s $24 billion discretionary budget” — and many experts fear that “Washington could have a difficult time shutting off the spigot” in the future. Some of these funds are tied to the recession and COVID-19, but most simply wouldn’t exist but for the President’s tariffs and, of course, the subsequent lobbying:

Not all farmers received special payouts during the last three years, but the Trump administration has recently moved to ensure that those in critical states do not miss out. That includes the tobacco industry, which was prohibited from receiving any of the trade assistance because of legal restrictions against subsidizing the sector. In September, the Agriculture Department quietly shifted some of the funds that were allocated to its Commodity Credit Corporation fund — which legally cannot subsidize tobacco — into a separate account that can bankroll the crop. Tobacco farmers will receive up to $100 million in payments, easing some of the financial pain that has been felt particularly hard in the battleground state of North Carolina.…

Graham Boyd, the executive vice president of the Tobacco Growers Association of North Carolina, secured subsidies for his crops after his group and lobbyists from other tobacco growing states demonstrated to the Agriculture Department that farmers were losing hundreds of millions of dollars per year in lost exports to China. North Carolina is America’s largest tobacco growing state and China was its biggest customer, but since 2018 Beijing has not bought American tobacco.

Any assessment of the tariffs and “trade wars” is thus incomplete without a thorough accounting of the immediate and long‐term cost of these subsidies — and other government efforts to paper over the inevitable problems that the President’s trade policies created — for both the economy and our political system.

Maybe trade wars aren’t good and easy to win after all.

Scott Lincicome is a Senior Fellow in Economic Studies, where he writes on international and domestic economic issues, including: international trade; subsidies and industrial policy; manufacturing and global supply chains; and economic dynamism. Scott also is a Senior Visiting Lecturer at Duke University Law School, where he has taught a course on international trade law, and he previously taught international trade policy as a Visiting Lecturer at Duke.

To read the original blog post, click here.