A recent report from Public Citizen’s Global Trade Watch alleges that trade policies during the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and World Trade Organization (WTO) era of “hyperglobalization” have inflicted disproportionate damage on U.S. Black and Hispanic workers.[1] Another new report from House of Representatives Ways and Means Committee Democrats claims: “For the last 50 years, the U.S. has pursued a policy of aggressive trade liberalization and experienced a painful decline in manufacturing…. The loss in manufacturing jobs disproportionately impacted Black workers in a multitude of ways.”[2] Those are serious allegations.

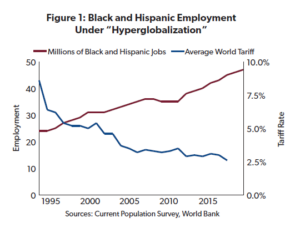

Since 1994, when NAFTA took effect and one year before the WTO was created, average world tariffs have fallen by nearly 70 percent.[3]

However, from 1994 to 2019 the United States also added 36.8 million new jobs. More than half of these new jobs were filled by Black and Hispanic workers, including nearly 18 million net new jobs for Hispanic Americans and 7.2 million net new jobs for Black workers.[4]

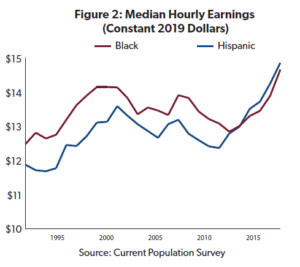

From 1994 to 2019, average real hourly earnings for Hispanic workers increased by 25.2 percent as average real hourly earnings for Black workers increased by 17.5 percent. The earnings gap between these two minority groups and White workers was smaller in 2019 than it was in 1994.

In contrast to suggestions that U.S. manufacturing has declined due to imports and outsourcing, real manufacturing output actually increased by 55 percent from 1997 to 2019.[6] Before the pandemic, U.S. manufacturing layoffs had been declining ever since 2001, the first year for which layoff statistics are available.[7]

Manufacturing job losses were overwhelmingly driven by technology, the opportunity for workers to move up to better jobs, and increases in the productivity of manufacturing workers, not by trade.[8] For example, the average manufacturing worker’s productivity doubled from 1990 to 2019, meaning fewer workers could produce more goods.

Even so, the trend toward lower manufacturing employment reversed course in 2010. From 2010 to 2019 the United States added nearly 1.4 million new manufacturing jobs.[10]

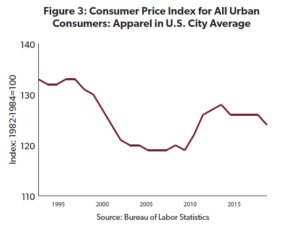

In addition to helping create millions of new, higher-paying jobs during the NAFTA/WTO era, international trade has reduced the cost of living for American workers and their families. For example, clothing is more affordable now than it was in 1994, after adjusting for inflation and quality factors, a change that benefits nearly all Americans.[11] The same goes for telephones, TVs, toys, and many other goods.

U.S. import taxes are regressive, meaning they disproportionately damage people with low incomes. A 2017 analysis by three former Obama administration economists, including the former Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, concluded: “Tariffs – taxes on imported goods – likely impose a heavier burden on lower-income households, as these households generally spend more on traded goods as a share of expenditure/income and because of the higher level of tariffs placed on some key consumer goods.”[12] Therefore reducing import tariffs is a progressive tax cut, with more benefits flowing to workers who earn less.

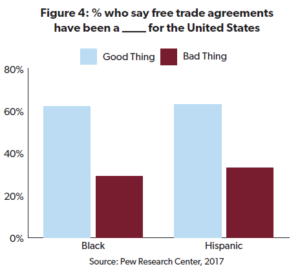

The record is clear: Trade has helped Black and Hispanic workers, who, not coincidentally, enthusiastically support trade. According to a 2017 Pew Research Center survey, large majorities of Black and Hispanic Americans think free trade agreements have been a good thing for the United States. Both groups were more likely to say that their financial situation has been helped by free trade agreements than hurt by them.[13]

The incoming Biden administration should strive to build on the benefits Americans have enjoyed as a result of declining global trade barriers. Specifically, the United States should do more to help Americans of all backgrounds by reducing import taxes on shoes, clothing, and other products that families need, while also cutting tariffs on imported inputs used by manufacturing workers to compete in the global marketplace.

To view the original brief, please click here

Do-Black-and-Hispanic-Workers-Benefit-from-Trade-1-[1] Rangel, Daniel, and Wallach, Lori. “Trade Discrimination: The Disproportionate, Underreported Damage to U.S. Black and Latino Workers From U.S. Trade Policies.” Public Citizen’s Global Trade Watch, January 2021. Retrieved from https://www.citizen.org/wp-content/uploads/PC_Trade-Discrimination-Report_1124.pdf.

[2] “Something Must Change: Inequities in U.S. Policy and Society.” Majority Staff Report, Committee on Ways and Means, U.S. House of Representatives, January 2021. Retrieved from https://waysandmeans.house.gov/sites/democrats.waysandmeans.house.gov/files/documents/WMD%20Health%20and%20Economic%20Equity%20Vision_REPORT.pdf.

[3] “Tariff rate, applied, weighted mean, all products (%).” The World Bank. Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/TM.TAX.MRCH.WM.AR.ZS. (Accessed January 12, 2021).

[4] “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey: Employment Level – Black or African American and Hispanic or Latino.” Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/data/. (Accessed January 12, 2021).

[5] “Weekly and hourly earnings data from the Current Population Survey: Median hourly earnings – in constant (base current year) dollars.” Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/data/. (Accessed January 12, 2021).

[6] “Real Value Added by Industry: Manufacturing.” Bureau of Economic Analysis. Retrieved from https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/index_industry_gdpIndy.cfm. (Based on data available for 1997 to 2019.)

[7] “Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey.” Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved from https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/dsrv?jt.

[8] See Hicks, Michael J., and Devaraj, Srikant. “The Myth and the Reality of Manufacturing in America,” Ball State University Center for Business and Economic Research, June 2015. Retrieved from https://projects.cberdata.org/reports/MfgReality.pdf.

[9] Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Major Sector Productivity and Costs: Manufacturing.” Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/data/#productivity.

[10] U.S. Department of Labor. (2020). “Employment by industry.” Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/charts/employment-situation/employment-levels-by-industry.htm. (Accessed January 9, 2021).

[11] “Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: Apparel in U.S. City Average.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved from https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CPIAPPSL (Accessed January 12, 2021.)

[12] Furman, Jason, Russ, Kathryn, and Shambaugh, Jay. “U.S. tariffs are an arbitrary and regressive tax,” VoxEU, January 12, 2017. Retrieved from: https://voxeu.org/article/us-tariffs-are-arbitrary-and-regressive-tax.

[13] Jones, Bradley. “Support for free trade agreements rebounds modestly, but wide partisan differences remain,” Pew Research Center, April 25, 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/04/25/support-for-free-trade-agreements-rebounds-modestly-but-wide-partisan-differences-remain/.