Introduction

The United States and European Union (EU) are each other’s largest trade and investment partners. Their ties are deep, but some barriers to trade and investment remain. Over the years, the two sides have sought to further liberalize trade and investment ties, enhance regulatory

cooperation, and work together on international economic issues of joint interest, including through international institutions such as the World Trade Organization (WTO).

The trading relationship is largely harmonious, but frictions emerge periodically due to the high level of commercial activity and disagreements on specific policy issues. U.S.- EU trade and economic relations face heightened tension now due to shifts in certain U.S. trade policy approaches under the Trump Administration.

Selected Issues

Trade Balance and Trade Practices

In 2018, the United States had an overall $115 billion trade deficit in merchandise and services with the EU, as the merchandise deficit ($170 billion) outweighed the services surplus ($55 billion) (see Figure 1). Germany, at $69 billion, accounted for the fourth-largest U.S. bilateral

merchandise trade deficit, after China, Mexico, and Japan.

The causes and consequences of trade deficits are debated. President Trump, who prioritizes reducing U.S. bilateral trade deficits, blames EU trade policies, and particularly those of Germany, for the U.S. merchandise trade deficit with the EU. The President also is critical of the U.S.-EU imbalance on auto trade, flagging disparate tariff levels (for cars, EU tariff is 10% and U.S. tariff is 2.5%; for trucks, EU tariff is 22% and U.S. tariff is 25%). EU leaders argue that the trade relationship is fair and mutually beneficial, observing, for example, that some EU auto companies have manufacturing facilities in the United States that support U.S. jobs and exports. Most economists say that the U.S. merchandise trade deficit is due to macroeconomic

variables rather than trade practices.

Trade Frictions

A major point of tension is the Trump Administration’s focus on unilateral trade measures such as tariffs. In 2018, the United States began applying tariffs of 25% and 10% on certain imports of steel and aluminum, under the national security-based “Section 232” trade law. The Administration granted some countries exceptions to the tariffs, but not to the EU. Despite the U.S. national security justification, the EU views the U.S. tariffs to be inconsistent with WTO rules on safeguard measures (which protect domestic industries from rising imports). The EU, accounting for one-fifth of U.S. steel imports and less than one-tenth of U.S. aluminum imports in 2018, applied retaliatory tariffs of 10% to 25% on about $3 billion of U.S. products (e.g., steel, whiskies, beauty products, yachts, and motorcycles), and may apply a second round of tariff increases in 2021. Both sides are now pursuing cases in the WTO on the respective measures.

Another source of friction is potential Section 232 tariffs on autos and auto parts. On May 17, 2019, the President announced that a Commerce Department investigation found that auto imports threaten to impair U.S. national security, granting the President the authority to impose import restrictions, including tariffs. The President directed the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) to negotiate with the EU, Japan, and other relevant trading partners to address the threat and report on its progress within 180 days.

Economic and Policy Impacts

Concerns are heightened over potential tit-for-tat escalation of tariffs on traded goods, adverse overall economic effects, and implications for EU-U.S. cooperation on global economic issues (e.g., steel and aluminum overcapacity). Harley-Davidson was the first U.S. firm to announce plans to shift some production overseas to avoid retaliatory tariffs by the EU, its largest overseas market for motorcycles. Economic impacts could be larger if tariff increases are imposed on autos, a top U.S. import from the EU.

Frictions also may rise in the 14-year-long U.S.-EU “Boeing-Airbus” cases in the WTO. The United States and EU announced preliminary lists of their traded goods on which they propose to impose countermeasure tariffs of about $11 billion and $12 billion, respectively—the

estimated harm that each claims the other’s subsidies on its respective domestic civil aircraft industry have caused the other. A final WTO assessment is expected in summer 2019 on appropriate countermeasure value amounts.

The United States continues to monitor other EU overall and country-specific policy developments, such as on data protection, digital trade, and penalties for corporate tax avoidance, some of which the United States sees as trade barriers. On July 10, 2019, the USTR initiated a “Section 301” investigation of France’s recently introduced digital services tax, based on concerns that the tax will discriminate against U.S.-based technology companies. Other developments may mitigate U.S.-EU frictions (see below).

WTO and Multilateralism

In the post-World War II era, the United States and EU have led in developing and liberalizing the rules-based international trading system, thereby contributing to its stability. EU officials are deeply troubled by the Trump Administration’s skepticism of the WTO, its periodic threats to not abide by WTO decisions over trade disputes that it finds contrary to U.S. interests and to withdraw the United States from the WTO, and its continuation of the Obama Administration practice of blocking new appointments to the WTO appellate body based on concerns about the WTO Dispute Settlement (DS) process.

Yet, the United States and EU, along with many other WTO members, are actively discussing potential WTO reform, including changes to DS. In addition, among other things, the United States continues to work through the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) on a multilateral agreement to address taxation issues posed by the digital economy. Nevertheless, many in the EU are concerned about a broader U.S. shift away from international cooperation, citing, for instance, the U.S. withdrawal from the 2015 nuclear deal with Iran. The Trump Administration’s skepticism of the EU’s multilateral nature, which precludes bilateral U.S. trade agreements

with individual EU member states, adds to frictions.

U.S.-EU Trade Negotiations

The United States and EU trade on WTO most-favorednation (MFN) terms, because there is no U.S.-EU free trade agreement (FTA) granting more preferential terms. U.S. and EU tariffs are generally low (simple average MFN applied tariff was 3.5% for the United States and 5.2% for the EU), but high on some sensitive products. Some regulatory and other nontariff barriers also may raise trading costs. On October 16, 2018, the Trump Administration notified Congress under Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) of new broad-based U.S. trade agreement negotiations with the EU.

The Administration seeks a “fairer, more balanced” U.S.- EU relationship. The TPA notification followed the July 2018 Joint Statement (agreed between President Trump and European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker) that aimed to de-escalate trade tensions. The negotiations have not started formally, largely due to lack of U.S.-EU consensus on their scope. While U.S. negotiating objectives include agriculture, the EU mandate to negotiate on tariffs excludes the sector. U.S.-EU differences also remain in such areas as government procurement, digital trade, regulatory cooperation, and geographical indications (GIs).

President Trump has threatened the EU repeatedly with tariffs, including over its exclusion of agriculture. The EU asserts that it will stop negotiating if it is subject to new Section 232 tariffs. Whether a U.S.-EU trade agreement, if concluded, would meet congressional expectations or TPA negotiating objectives and other requirements is unclear. Meanwhile, U.S.-EU sector-specific regulatory cooperation is ongoing, such as on pharmaceuticals. In August 2019, the two sides concluded a new deal on greater market access for U.S. beef exports to the EU.

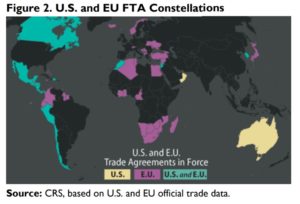

The United States and EU each has its own constellation of FTAs—14 FTAs with 20 countries in force for the United States and over 40 trade agreements for the EU (see Figure 2). In the absence of a U.S.-EU FTA, U.S. businesses are disadvantaged in the EU market relative to such trading partners as Canada, Japan, and Vietnam, with whom the EU recently concluded FTAs. An FTA also could be significant strategically in jointly shaping global “rules for the road” on new issues and, for instance, with respect to China.

Brexit

The UK’s pending exit from the EU presents some uncertainty for U.S.-EU economic relations. An EU without the UK would remain the United States’ largest trading partner, but the outcome of EU-UK negotiations on their future trade and economic relationship could affect U.S. commerce. Many U.S. firms have a significant presence in the UK, and use the UK as a platform to access the EU market. Brexit also could have implications for U.S. commercial interests in terms of tariffs, customs procedures, or regulatory requirements. The United States

and UK are interested in negotiating a bilateral FTA. While an EU member, the UK cannot negotiate trade agreements with other countries, as the EU retains exclusive competence over its trade policy.

Issues for Congress

Potential issues in U.S.-EU trade relations include:

Historically, how have U.S.-EU trade relations bolstered the U.S. economy and prosperity, or had negative implications?

How do recent U.S.-EU trade developments affect the U.S. and global economy and the international trading system? What are the options to resolve current U.S.-EU trade frictions? Should the President’s authority under U.S. trade laws be modified?

What are the implications of the Administration linking Section 232 national security action to broader trade negotiations with the EU How do U.S.-EU frictions affect potential cooperation on economic issues of joint concern, such as regarding China?

What are the benefits and costs of further liberalizing U.S.-EU trade—including through the proposed trade negotiations, ongoing regulatory cooperation, potential sector-specific tariff liberalization, and potential multilateral trade liberalization?

See CRS In Focus IF10931, U.S.-EU Trade and Economic

Issues, by Shayerah Ilias Akhtar; and CRS Report R45745,

Transatlantic Relations: U.S. Interests and Key Issues,

coordinated by Kristin Archick.

To read original report, click here

CRS US EU Trade