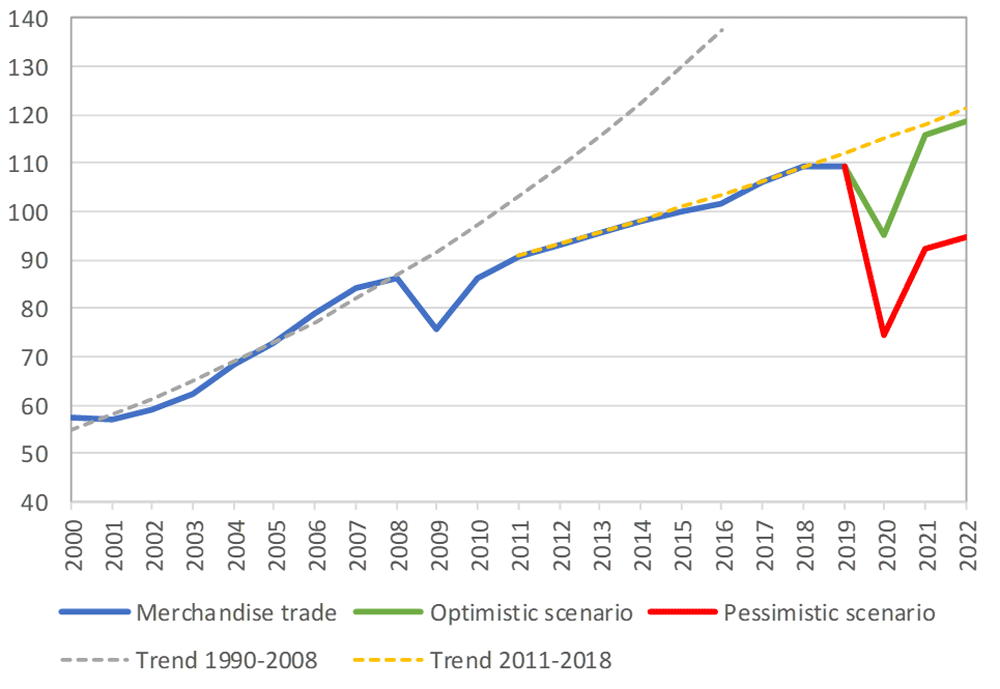

World trade is expected to fall by between 13% and 32% in 2020 as the COVID 19 pandemic disrupts normal economic activity and life around the world.

The wide range of possibilities for the predicted decline is explained by the unprecedented nature of this health crisis and the uncertainty around its precise economic impact. But WTO economists believe the decline will likely exceed the trade slump brought on by the global financial crisis of 2008‑09 (Chart 1).

Estimates of the expected recovery in 2021 are equally uncertain, with outcomes depending largely on the duration of the outbreak and the effectiveness of the policy responses.

“This crisis is first and foremost a health crisis which has forced governments to take unprecedented measures to protect people’s lives,” WTO Director-General Roberto Azevêdo said.

“The unavoidable declines in trade and output will have painful consequences for households and businesses, on top of the human suffering caused by the disease itself.”

“The immediate goal is to bring the pandemic under control and mitigate the economic damage to people, companies and countries. But policymakers must start planning for the aftermath of the pandemic,” he said.

“These numbers are ugly – there is no getting around that. But a rapid, vigorous rebound is possible. Decisions taken now will determine the future shape of the recovery and global growth prospects. We need to lay the foundations for a strong, sustained and socially inclusive recovery. Trade will be an important ingredient here, along with fiscal and monetary policy. Keeping markets open and predictable, as well as fostering a more generally favourable business environment, will be critical to spur the renewed investment we will need. And if countries work together, we will see a much faster recovery than if each country acts alone.”

Chart 1 – World merchandise trade volume, 2000‑2022

Index, 2015=100

Source: WTO Secretariat.

Trade was already slowing in 2019 before the virus struck, weighed down by trade tensions and slowing economic growth. World merchandise trade registered a slight decline for the year of ‑0.1% in volume terms after rising by 2.9% in the previous year. Meanwhile, the dollar value of world merchandise exports in 2019 fell by 3% to US$ 18.89 trillion.

In contrast, world commercial services trade increased in 2019, with exports in dollar terms rising by 2% to US$ 6.03 trillion. The pace of expansion was slower than in 2018, when services trade increased by 9%. Details on merchandise and commercial services trade developments are presented in Appendix Tables 1 through 4 and can be downloaded from the WTO Data Portal at data.wto.org.

Outlook for trade in 2020 and 2021

The economic shock of the COVID-19 pandemic inevitably invites comparisons to the global financial crisis of 2008-09. These crises are similar in certain respects but very different in others. As in 2008-09, governments have again intervened with monetary and fiscal policy to counter the downturn and provide temporary income support to businesses and households.

But restrictions on movement and social distancing to slow the spread of the disease mean that labour supply, transport and travel are today directly affected in ways they were not during the financial crisis. Whole sectors of national economies have been shut down, including hotels, restaurants, non-essential retail trade, tourism and significant shares of manufacturing.

Under these circumstances, forecasting requires strong assumptions about the progress of the disease and a greater reliance on estimated rather than reported data.

Future trade performance as summarized in Table 1 is thus best understood in terms of two distinct scenarios: (1) a relatively optimistic scenario, with a sharp drop in trade followed by a recovery starting in the second half of 2020, and (2) a more pessimistic scenario with a steeper initial decline and a more prolonged and incomplete recovery.

These should be viewed as explorations of different possible trajectories for the crisis rather than specific predictions of future developments. Actual outcomes could easily be outside of this range, either on the upside or the downside.

Under the optimistic scenario, the recovery will be strong enough to bring trade close to its pre-pandemic trend, represented by the dotted yellow line in Chart 1, while the pessimistic scenario only envisages a partial recovery. Given the level of uncertainties, it is worth emphasizing that the initial trajectory does not necessarily determine the subsequent recovery.

For example, one could see a sharp decline in 2020 trade volumes along the lines of the pessimistic scenario, but an equally dramatic rebound, bringing trade much closer to the line of the optimistic scenario by 2021 or 2022.

After the financial crisis of 2008-09, trade never returned to its previous trend, represented by the dotted grey line in the same chart. A strong rebound is more likely if businesses and consumers view the pandemic as a temporary, one-time shock.

In this case, spending on investment goods and consumer durables could resume at close to previous levels once the crisis abates. On the other hand, if the outbreak is prolonged and/or recurring uncertainty becomes pervasive, households and business are likely to spend more cautiously.

Under both scenarios, all regions will suffer double-digit declines in exports and imports in 2020, except for “Other regions” (which is comprised of Africa, Middle East and Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) including associate and former member States).

This relatively small estimated decline in exports stems from the fact that countries from these regions rely heavily on exports of energy products, demand for which is relatively unaffected by fluctuating prices.

If the pandemic is brought under control and trade starts to expand again, most regions could record double-digit rebounds in 2021 of around 21% in the optimistic scenario and 24% in the pessimistic scenario – albeit from a much lower base (Table 1). The extent of uncertainty is very high, and it is well within the realm of possibilities that for both 2020 and 2021 the outcomes could be above or below these outcomes.

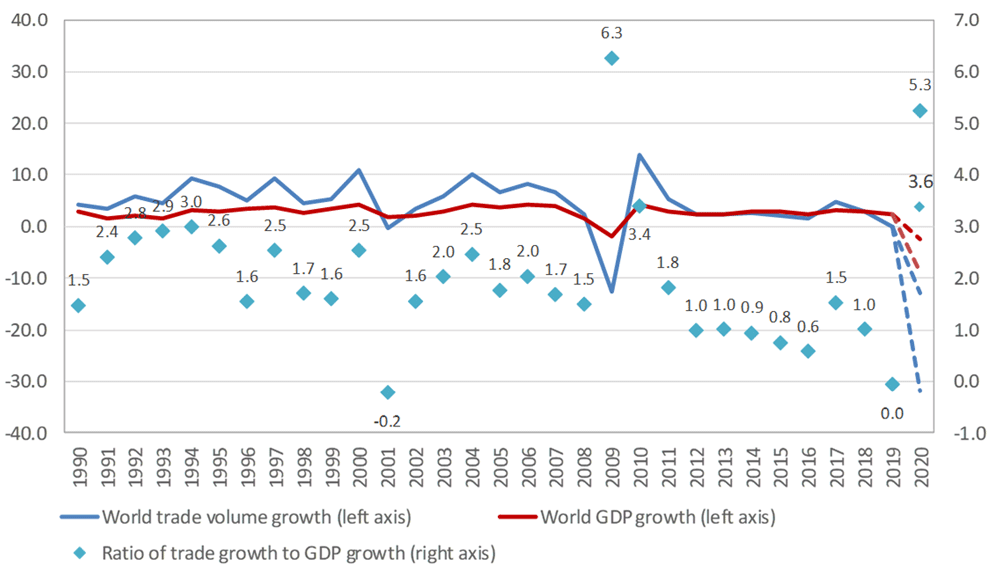

Chart 2 – Ratio of world merchandise trade growth to world GDP growth, 1990‑2020

% change and ratio

Source: WTO Secretariat for trade and consensus estimates for historical GDP. Projections for GDP based on scenarios simulated with WTO Global Trade Model.

Two other aspects that distinguish the current downturn from the financial crisis are the role of value chains and trade in services. Value chain disruption was already an issue when COVID‑19 was mostly confined to China. It remains a salient factor now that the disease has become more widespread. Trade is likely to fall more steeply in sectors characterized by complex value chain linkages, particularly in electronics and automotive products.

According to the OECD Trade In Value Added (TiVa) database, the share of foreign value added in electronics exports was around 10% for the United States, 25% for China, more than 30% for Korea, greater than 40% for Singapore and more than 50% for Mexico, Malaysia and Vietnam. Imports of key production inputs are likely to be interrupted by social distancing, which caused factories to temporarily close in China and which is now happening in Europe and North America.

However, it is also useful to recall that complex supply chain disruption can occur as a result of localized disasters such hurricanes, tsunamis, and other economic disruptions. Managing supply chain disruption is a challenge for both global and local enterprises and requires a risk-versus-economic efficiency calculation on the part of every company.

Services trade may be the component of world trade most directly affected by COVID-19 through the imposition of transport and travel restrictions and the closure of many retail and hospitality establishments. Services are not included in the WTO’s merchandise trade forecast, but most trade in goods would be impossible without them (e.g. transport).

Unlike goods, there are no inventories of services to be drawn down today and restocked at a later stage. As a result, declines in services trade during the pandemic may be lost forever. Services are also interconnected, with air transport enabling an ecosystem of other cultural, sporting and recreational activities. However, some services may benefit from the crisis.

This is true of information technology services, demand for which has boomed as companies try to enable employees to work from home and people socialise remotely. The impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on international trade is not yet visible in most trade data but some timely and leading indicators may already yield clues about the extent of the slowdown and how it compares to earlier crises.

Indices of new export orders derived from Purchasing Managers’ Indices (PMIs) are particularly useful in this regard. The JP Morgan global PMI for March showed export orders in manufacturing sinking to 43.3 relative to a baseline value of 50, and new services export business dropping to 35.5, suggesting a severe downturn.

Chart 3: New export orders from purchasing managers indices, Jan. 2008 – Mar. 2020

Index, base=50

Note: Values greater than 50 indicate expansion while values less than 50 denote contraction.

Source: IHS Markit.

pr855_e

To view the full report, click here.