When economists model changes in tariffs, their models make assumptions about the impact of those changes. The column argues that those assumptions are often contradicted in the real world and proposes an approach that relaxes these restrictions. Estimates using this approach show that customary models may severely underestimate the impact of recent tariff increases.

Trade disputes – if not wars – are in fashion again, and the trade liberalisation hype of the 1990s has come to an end, at least for now. Almost weekly, we are confronted with threats to undermine trade liberalisation, and economists are kept busy quantifying potential consequences for exports, imports, and the economy as a whole.

When economists consult the WTO, governments, or other NGOs about, let’s say, a US government announcement of a 10-percentage-point increase in the tariff factor on Chinese goods, how do they proceed? And what are their underlying assumptions?

Three trade model assumptions

Models of varying sophistication have been used to quantify the benefits of the EU (Baldwin et al. 1997), of NAFTA (Caliendo and Parro 2015), of TTIP (Felbermayr et al. 2016), or of Brexit (Breinlich et al. 2016). These – and many other models of trade – have three assumptions in common:

1. If an ad valorem tax is increased or reduced by some value in percent, the price to the customer is directly altered to the same extent. This is precisely what an ad valorem tax (such as a proportional tariff) is meant to be. Suppose wine and beer both cost $10 per bottle before tariffs, but the rate on wine is 10%, whereas that on beer is 5%. Then, the tariff factors for these two goods are 1.1 and 1.05, respectively. The direct effects of a tariff are, under this assumption, fully captured by the percentage increase in prices.

There are at least five arguments against this assumption. First, just as with income tax evasion, tariffs can be avoided by smuggling, or through strategic misdeclarations at customs (importing wine as water, understating the value or price). Second, some trade policy measures alter prices non-proportionately. Oil, for example, varies tariffs by quantity. Other tariffs vary by units of a product, rather than by value. Third, some zero-tariff opportunities – entering a free trade zone for example – are underused because firms want to avoid paperwork which has higher costs than the tariff. In this common case, a trade agreement is partially ineffective.

Fourth, if countries guarantee a tariff that is high, but apply one that is much lower, the sensitivity of customers to the expected tariff is important, not to the applied tariff, as the expected tariff can be anything up to the bound (guaranteed) one. This was the case with the US against China before China joined the WTO. In this case, the sensitivity of customers to prices also depends on their risk aversion, and on the gap between applied and bound tariffs beyond the sensitivity of demand to known prices. Finally, higher policy trade barriers may simply lead to fewer consumers buying foreign products. In this case, the tariff sensitivity of aggregate customer demand depends both on the sensitivity of customers who buy before and after the change, and ones who will stop or start consuming because of it.

Virtually all models assume such an identical, one-for-one, log-linear (proportional) relationship between tariff or ad valorem non-tariff barriers and customer prices and sales. Heterogeneous tariff effects must then be fully attributable to model-induced indirect effects.

2. Customary quantitative trade models have another restriction: they focus on tariffs. Non-tariff barriers include specific checking routines at borders and the implementation of standards and procedures to protect domestic suppliers. In contrast to tariffs, certain non-tariff barriers might have trade-enhancing effects, for instance they may create trust in products through standards or decreasing transaction costs (WTO 2012). Non-tariff policy regulations have become extremely important since the Uruguay Round (Horn et al. 2010). They are less transparent than the use of tariffs, but they received more attention in the era of ‘new’ protectionism that we can date from the beginning of the Global Crisis (Bown 2011, Baldwin and Evenett 2012, Bown and Crowley 2013). If they consider non-tariff trade barriers at all, most studies do not treat them as interdependent with tariffs. This interdependence, though, might alter the direct effect of a tariff as non-tariff-barriers vary.

3. The direct effect of trade policy barriers on trade costs and trade flows is typically assumed to be random, conditional on a log-linear function of country size, costs or prices, and other trade costs. However, if trade policymaking (agreeing to a specific tariff level, or non-tariff standards) uses a different or more complex process, this assumption would be violated. This would lead to so-called endogenous trade policy. If it is considered at all, endogeneity of trade policy is considered in academic work about (binary) membership trade agreements between countries.

We can clearly reject randomness of trade policy, however, on both theoretical and empirical grounds. Economic theory suggests that – even in the absence of lobbying and interest-group activity – countries choose tariffs and non-tariff barriers in a way that benefits them. Empirical work on endogenous trade-agreement membership suggests that the granting of lower tariff barriers and other facilitations in trade agreements should not be treated as random. When we do, it leads to biased direct (and, consequently, total) effects of trade policy on outcomes such as trade flows or real consumption (consumer welfare).

Relaxing the assumptions

We have developed a quantitative framework of partial and total trade policy effects on trade costs and trade flows that relaxes the aforementioned three archetypical assumptions (Egger and Erhardt 2019). It builds on a generic multi-country, multi-sector quantitative framework, consistent with leading models of international economic theory.

We propose a multi-step approach:

- First, trade data are decomposed to extract information on exogenous producer-country-sector supply fundamentals (productivity, absolute factor endowments, preferences towards the goods of a country) and trade costs.

- Second, machine-learning algorithms are used to model the explainable part of tariff and non-tariff barriers using these fundamentals and natural, non-policy trade cost measures (geography, historical ties, common language and culture). In this way, we decompose country-pair-sector tariff and non-tariff barriers into two parts: a flexible (non-parametric) function of supply fundamentals and natural trade costs in two partner countries as well as the rest of the world, and the rest – a between-country-pairs independent, random component that may have an arbitrary (nonparametric) bivariate distribution, meaning that unobservable random influences on tariffs may be correlated with ones on non-tariff barriers.

- Third, overall (policy plus non-policy) bilateral trade costs as distilled from bilateral trade-flow data are modelled as a flexible function of tariff and non-tariff barriers, as well as the joint density of their random components. This establishes a ‘dose-response’ function, as in medical trials where we are interested in how variations in the intensity of chemical substances contained in drugs play affect the health of patients. We are interested in something conceptually similar, namely, how different tariff and non-tariff barrier levels affect trade costs and, ultimately, trade flows.

- Fourth, the heterogeneous direct effects of tariff and non-tariff barriers on trade costs are fed into the aforementioned customary multi-country-multi-sector general-equilibrium model. This is done to compare responses of economic outcomes between the flexible approach we propose, and the one which is typically applied. Recall that the typical approach assumes homogeneous direct effects of tariff and non-tariff barriers on trade costs for a product, independent of the level of tariff and non-tariff barriers.

Figure 1 Partial direct effects of tariff and non-tariff barriers (NTBs) for different levels of tariff and non-tariff barriers

A large set of country-pair-sector data clearly rejects the assumption of the homogeneity of partial effects of ad valorem log tariff (and also log non-tariff) factor rates on trade costs. Therefore the ubiquitous assumption of log-linearity appears to be wrong!

In particular, we find that the marginal effect of an increase in tariffs is very strong for very low tariff barriers, but weak for tariff rates of around 10%. The marginal impact is much stronger again for intermediate levels of tariffs. This implies a particularly strong impact when increasing initially low trade barriers. Any increase in tariffs creates strong adverse reactions, potentially because it indicates the end of good trade relationships.

In contrast, a change in tariffs from 10% to 15% will hardly change trade flows directly. In this case, trade was medium free ex ante, and these changes are not particularly severe. If tariffs rise beyond this intermediate level, changes in trade policy might signal a move towards a potentially long-lasting adverse trade policy environment, which induces a much stronger effect.

Once a particular threshold of tariff barriers is passed, the partial effect is much weaker and often close to zero for very high tariff barriers, especially if non-tariff barriers are high. Hence, further raising tariffs that are already very high does not have a discernible effect, and even less so when non-tariff barriers are also high. This is consistent with research showing that tariffs become irrelevant due to tax fraud (smuggling or misdeclarations) when tariffs are high. This is entirely ignored in quantitative work on trade.

Non-tariff barriers increase trade costs, in particular, for very low levels of non-tariff barriers. For medium levels of non-tariff barriers, marginal effects on trade costs can actually be trade-cost-reducing. We show that this is due to the beneficial (standard-setting) effects of some technical barriers to trade.

Modelling trade costs

Using this information, we evaluate the effect of that unilateral increase in US tariffs on Chinese imports of 10 percentage points. A customary ad valorem approach to modelling trade costs would severely underestimate the effect, compared to our flexible approach.

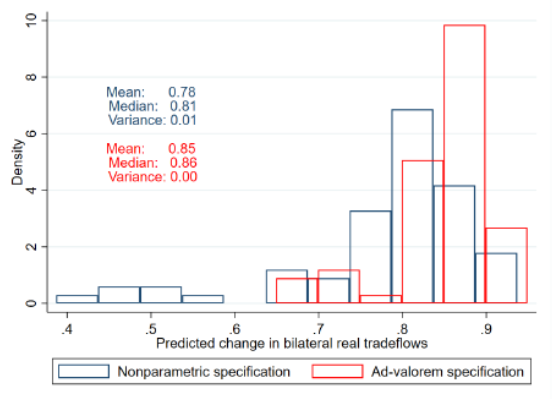

The average real bilateral reduction of US imports from China in this experiment is about 7 percentage points larger under a flexible-gradient approach than in the customary approach. This implies underestimation of the effect by almost 50%. For some sectors the differences in predicted outcomes are as large as 27 percentage points in absolute value. Figure 2 shows these results.

Figure 2 General equilibrium change in bilateral real trade flows for different sectors in the non-parametric versus the ad-valorem specification of trade costs

References

Baldwin, R E and S J Evenett (2012), “Beggar-thy-neighbour Policies During the Crisis Era: Causes, Constraints and Lessons for Maintaining Open Borders”, Oxford Review of Economic Policy 28(2): 211-234.

Baldwin, R E, J Francois, and R Portes (1997), “The Costs and Benefits of Eastern Enlargement: The Impact on the EU and Central Europe”, Economic Policy 12: 125-176.

Bown, C P (2011), “Taking Stock of Antidumping, Safeguards and Countervailing Duties, 1990-2009”, The World Economy 34(12): 1955-1998.

Bown, C P and M A Crowley (2013), “Import Protection, Business Cycles, and Exchange Rates: Evidence from the Great Recession”, Journal of International Economics 90(1): 50-64.

Breinlich, H, S Dhingra, S Estrin, H Huang, G Ottaviano, T Sampson, J Van Reenen, and J Wadsworth( 2016), BREXIT 2016 – Policy Analysis from the Centre for Economic Performance,Centre for Economic Performance.

Egger, P and K Erhardt (2019), “Heterogeneous Effects of Tariff and Non-tariff Trade-Policy Barriers in Quantitative General Equilibrium”, CEPR discussion paper 13602.

Felbermayr, G, R Aichele, and I Heiland (2016), “Going Deep: The Trade and Welfare Effects of TTIP Revised”, ifo working paper series 219, ifo Institute.

Horn, H, P C Mavroidis, and A Sapir (2010), “Beyond the WTO? An Anatomy of EU and US Preferential Trade Agreements”, The World Economy 33 (11): 1565-1588.

WTO (2012), World Trade Report 2012: Trade and Public Policies: A Closer Look at Non-tariff Measures in the 21st Century, World Trade Organization.

[To read the original column, click here.]

Copyright © 2019 VoxEU. All rights reserved.