While the trade system as a whole has proved more resilient than many feared during the Covid-19 pandemic, the crisis has placed new stresses on multilateral cooperation. This has come at a time when the standing of the WTO has fallen in some of its largest members and its rules have been ignored by many. This column argues that with the election of a new US government and the concurrent selection of a new WTO Director-General, there is new hope for a revitalisation of multilateral cooperation on trade. A new eBook presents analyses and ideas of how this could be done.

Multilateral cooperation on international trade is under severe strain. The standing of the WTO has fallen in some of its largest members and its rules have been ignored by many. The US’ commitment to multilateralism was drastically curtailed under the Trump administration. The US purposefully undermined the functioning of the WTO and eschewed multilateral cooperation, embracing aggressive unilateralism instead (Blustein 2019, Davis and Wei 2020, Irwin 2017, van Grasstek 2019, Zeollick 2020). Other members responded with unilateralism of their own.

Download Revitalising Multilateralism: Pragmatic Ideas for the New WTO Director-General here

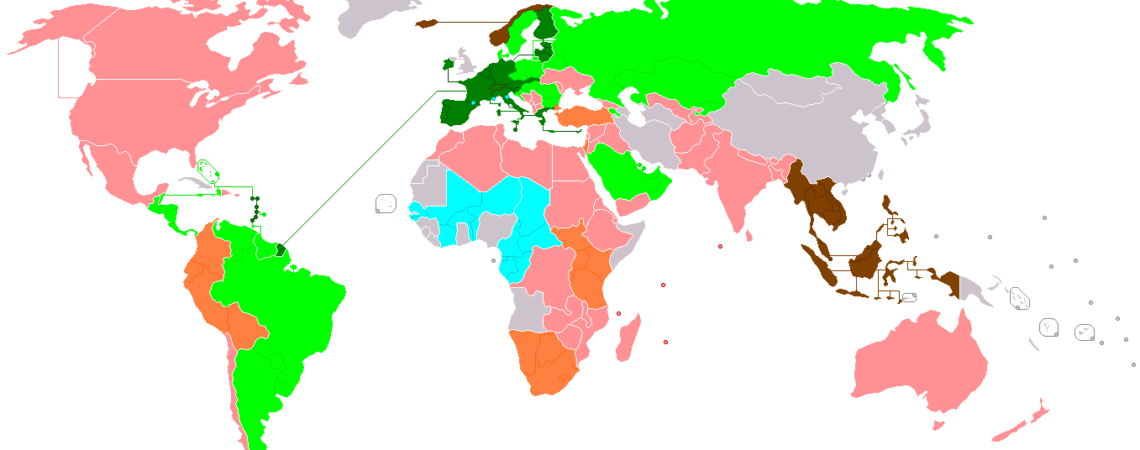

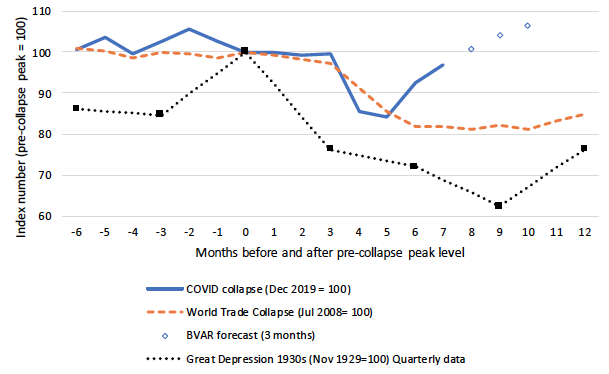

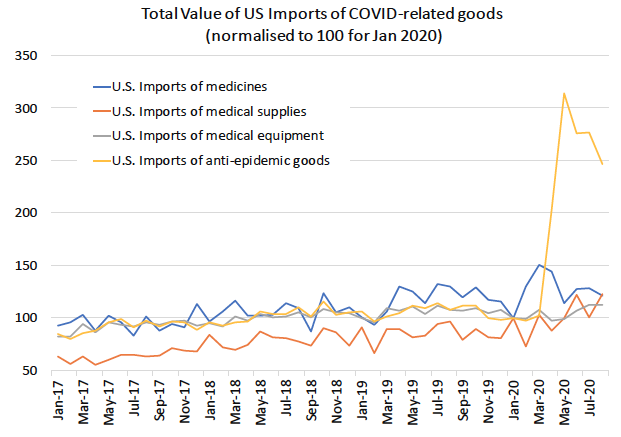

The pandemic has created a new set of shocks. The trade system as a whole has proved more resilient than many feared (Figure 1), and the trade response on medical supplies has been particularly impressive (Figure 2). Quite simply, many doctors and nurses in North America and Europe would be fighting the second wave with a shortage of protective equipment were it not for the massive imports from East Asia. The crisis, however, has placed new stresses on multilateral cooperation. Members have thrown up a wide range of pandemic-linked trade restrictions and committed themselves to potentially trade-distorting industrial policies. The sense of disarray and the lack of trust are palpable.

Figure 1 Comparing the Covid collapse to the 2008/09 world trade collapse and the Great Depression

Note: BVAR: Bayesian vector autoregression.

Sources: Eichengreen, and O’Rourke (2009) and CPB World Trade Monitor (data through to July 2020). See also https://voxeu.org/article/covid-19-and-world-merchandise-trade

Figure 2 Foreign suppliers of medicat kit and medicines came to the rescue of US hospitals and patients

Note: Anti-epidemic goods are a class of products including alcohol solutions, hand santisers, masks, and soap.

Source: Assembled from 10-digit US import data available from the US International Trade Commission.

Yet, it would be wrong to overdo the pessimism. None of the 164 WTO members, not even the US, has left the organisation. To the contrary, 23 nations are seeking to join the WTO. Moreover, there is widespread acceptance that the WTO needs to be reformed. ‘Mend it, don’t end it’, as the saying goes.

The WTO is worth fixing to help tackle today’s global challenges

Humanity faces massive global challenges in the years ahead, and the solutions to these will require cooperation between governments and other stakeholders around the globe. International commerce will be part of those cooperative solutions. That alone is a compelling reason why the WTO needs fixing.

The WTO is not the only place for working on such solutions, but it is a vital one. The WTO’s basic rules – like reciprocity, non-discrimination, and transparency – are arguably the most universally accepted. The basic WTO rules – which build on the GATT rules agreed in 1947 – had been written into the domestic lawbooks of many nations well before most of today’s national leaders were born. As such, the rules help align expectations for firms, governments, and civil society groups. This is an accomplishment worth building on.

The list of contemporary global challenges is long, but among these are:

- Facilitating the production and distribution of billions of doses of COVID-19 vaccines.

- Finding an ‘interface mechanism’ that allows different forms of capitalism to co-prosper.

- Fostering a global economic recovery.

- Addressing the challenges posed by climate change.

A window of opportunity for mending opened with the election of a new US government and the concurrent selection of a new WTO Director-General. There is new hope for a revitalisation of multilateral cooperation on trade.

The eBook posted today presents analyses and ideas that touch on a very broad range of topics and policies (Evenett and Baldwin 2020). In this column, we highlight a few of the ideas.

The WTO can be fixed – and here is how

We have no illusions that revitalisation will take time and will require starting with confidence-building measures. Still, a number of key building blocks are in place, not least the sense that the current stalemate and frictions serve no-one’s interests. Away from Geneva, there are many instances of governments engaging in trade cooperation – whether bilaterally, regionally, or in other formations, such as the Ottawa Group. Even in Geneva, work continues on the Joint Statement Initiatives and the COVID-19 pandemic has brought together groups of WTO members that have made declarations concerning their trade policy intent. Put simply, governments haven’t lost the knack for trade policy cooperation.

Nor have governments stopped integrating their economies into the world economy. By 30 October 2020, the Global Trade Alert had documented 554 unilateral policy interventions taken this year by governments around the world that liberalise their commercial policies. That’s more than double the number recorded at this time last year (249) and more than 50% higher than the comparable total in 2018, the year which saw the most trade reforms since the global financial crisis of 2008-9.

A total of 116 governments have taken steps that integrate their economies into the world trading system this year, or will implement measures doing so by the end of 2020. For all the doom and gloom about the world trading system’s prospects, it is worth recalling that the Global Trade Alert data imply that, since the first G20 Leaders’ Summit in November 2008, on average a government has undertaken a unilateral commercial policy reform every 14 hours. Governments haven’t given up on trade reforms either. And these unilateral reforms aren’t ones where the officials involved insisted on some reciprocal gesture by trading partners. We need to build on that.

Going forward, there is considerable merit in WTO members proceeding on two tracks.

- Identify together a new common denominator for the WTO that will define, in broad terms, the organisation’s purpose and trajectory in the decade ahead.

We elaborate on this in the introduction to the eBook, but the basic idea is to find a common denominator on what imperatives the WTO should accomplish over the next decade or so. That discussion is necessary as each WTO member needs to be convinced that there is an appropriate balance between rights and obligations, and gains and concessions.

- Develop and adopt confidence-building measures.

These would signal to all that the WTO is a place where governments can solve policy problems and where they lend each other support in normal trading conditions and, in particular, during times of crisis.

To kickstart revitalising multilateral trade cooperation, however, a series of confidence-building initiatives are needed. These initiatives don’t require bare-knuckled negotiations over binding commitments; rather, the goal is to channel the cooperative and reforming spirit mentioned at the start of this section into greater collaboration among WTO delegations in Geneva, supported by a re-motivated WTO Secretariat. Such confidence-building measures should include the following:

- Discussions about solutions to common problems, including those arising from arising from COVID-19 (e.g. resilience of supply chains), and steps to better to manage trade frictions arising from different types of capitalism (and the adequacy or otherwise of existing WTO accords in this respect).

- Negotiation of a Memorandum of Understanding on facilitating trade in medical goods and medicines that could later form the basis of a fully-fledged binding accord.

- Engagement with other bodies whose decisions seriously implicate cross-border commerce, including GAVI and others working on the production and distribution of a vaccine, as well as the steps taken by other bodies to revive sea- and air-based cross-border shipment.

- A more ambitious project would be a commitment to a moratorium on tariff hikes and other taxes on imports.

- Joint study of next generation trade issues including the trade-related aspects of the digital economy and the relationship between commercial policies and climate change.

- A review of the practices and operation of the WTO during crises, with an eye to ensuring extensive and sustained participation of members, stronger links and inputs to and from national capitals, and other pertinent organisational matters. The goal would be for the WTO membership to adopt a crisis management protocol.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu, that tireless campaigner against Apartheid, once remarked that “there is only one way to eat an elephant: one bite at a time”. After a decade of drift and backsliding, the task of revitalising multilateral trade cooperation may seem daunting. It may seem even more so after the disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic and the attendant slump in world trade.

Yet, in the same emergency lie the seeds of revival – especially if trade diplomats can demonstrate the relevance of the WTO to national governments fighting this pandemic – ideally through an accord that eases the cross-border shipment of needed medical goods and medicines. Step by pragmatic step, the WTO can regain its centrality in the world trading system.

Ultimately, the pandemic affords the opportunity to reframe discussions on multilateral trade cooperation away from the stalemate, the frustration of recent years between governments, and the Uruguay Round mindset that ran into diminishing returns years ago. Rather, discussions between governments need to draw lessons from the second global economic shock in 15 years so as to rebuild a system of global trade arrangements capable of better tackling systemic crises and, more importantly, better able to contribute to the growing number of first-order challenges facing societies in the 21st century. Doing so will require revisiting the very purpose of the WTO.

References

Blustein, P (2019), Schism: China, America, and the Fracturing of the Global Trading System, Center for International Governance Innovation.

Davis, B and L Wei (2020), Superpower Showdown: How the Battle Between Trump and Xi Threatens a New Cold War, Harper Collins.

Eichengreen, B and K O’Rourke. (2009), “A Tale of Two Depressions”, VoxEU.org, 7 April.

Evenett, S J and R E Baldwin (2020), Revitalising Multilateralism: Pragmatic Ideas for the New WTO Director-General, CEPR Press.

Irwin, D (2017), Clashing Over Commerce: A History of US Trade Policy, University of Chicago Press.

van Grasstek, C (2019), Trade and American Leadership: The Paradoxes of Power and Wealth from Alexander Hamilton to Donald Trump, Cambridge University Press.

Zeollick, R (2020), America in the World: A History of U.S. Diplomacy and Foreign Policy, Twelve: Hachette Book Group.