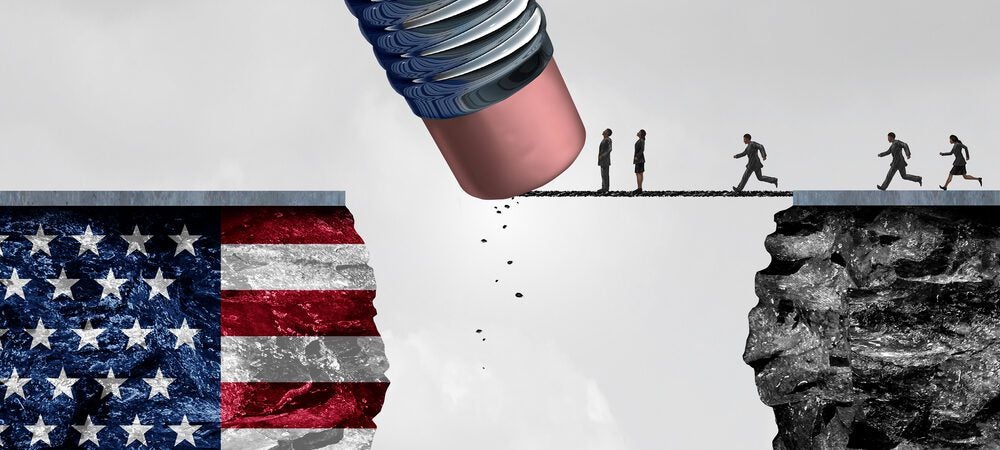

There has been an increasing interest in understanding the impact of international trade protectionism on the global organization and adaptive reconfigurations of value chain activities. The move towards protectionism started in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, with many economically developed governments enacting populist policies and measures encouraging the local sourcing of supplies in order to protect their local industries and jobs. Such policy interventions have attracted significant interest, which was stimulated by the attempt made by the 45th President of the United States, Donald Trump, to surrender the US’s global leadership and replace it with a more inward-looking and fortress-like mentality, which led to the US-China trade war. This significant shift of globalization toward international trade protectionism emphasizes the implicit assumption – made by the international business (IB) literature over the past decades – that globalization is ongoing and accelerating. Under this assumption, the dominant IB studies have examined the causes of globalization and its effects on the activities of multinational enterprises (MNEs). In contrast, relatively limited studies have paid attention to the reverse processes – i.e., ‘de-globalization’ or ‘anti-globalization’ related protectionism measures – and their implications for the reconfiguration of GVCs. As some estimates suggest that around 80% of global trade is undertaken through GVCs, and in such a context protectionism measures and trade wars between the USA and China can have significant consequences for the GVCs. Rising protectionism also reflects the slowing down of globalization, suggesting far reaching implications for firms.

This research gap is amplified by the significant numbers of pro-market and pro-globalization reforms that many of the emerging Asian and Latin American economies have enacted in the early twenty-first century with the aim of providing MNEs with significant opportunities to fine slice their GVC activities in terms of integrating, coordinating, and communicating with geographically dispersed partners to co-create value and of effectively competing in the global marketplace. The organization of global economic activities under GVCs has enabled global learning and the rapid expansion of ideas through the exchange of technology and human capital, thus contributing to lower production costs, higher specialization levels, and more innovative products and services. The resulting vibrant international economic activities have also promoted societal welfare and fostered wealth and job creation. Furthermore, GVCs’ role is becoming extremely important in achieving sustainable economic growth and development and given these benefit, several international organizations have made GVCs as part of their policymaking agenda. Various countries from Asia to Latin America have benefited through their insertion into GVCs. For instance, the participation of southern-based small suppliers in GVCs has been noted to be crucial in improving their so-called economic upgrading prospects through the flow of valuable knowledge from lead firms – MNEs. Economic upgrading refers to a process whereby economic actors – countries and firms – move to higher value activities in GVCs. It is also considered to be their passport to entry into international markets.

To address the aforementioned gaps in the extant literature, our study built on the nexus between the de-globalization and GVCs literature to investigate the impact of international trade protectionism on the reconfiguration of GVCs and further explore its boundary conditions. Specifically, we aimed at answering the following two fundamental questions: (1) “What are the implications of international trade protectionism for GVCs?” and (2) “What risk mitigation response strategies are suited to manage trade protectionism and develop resilient GVCs?” In answering these two questions, we focused on a set of US protectionism measures enacted during the Trump era and maintained by the current administration of President Biden, and discussed their implications for the reconfiguration of GVCs in terms of their control and coordination. This context is important in light of the aggressive protectionist measures enacted by the US against China and other trading partner countries – which have led to the decoupling of value chain activities. For instance, the USA has withdrawn from the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement, renegotiated free trade agreements with Mexico and Canada under the umbrella of NAFTA, and enacted a range of new tariffs on goods and services. In addition, MNEs, as lead firms from the US, are the major actors behind the global organization and coordination of GVCs; thus, such context provides important insights into the changing geography of GVCs as well as their resilience. To understand the US trade protectionism measures and their implications for GVCs, we examined 174 newspaper articles published between 2016 and 2020 in broadsheet newspapers (The New York Post, The New York Times, and Newsday) and specialist business publications (The Financial Times, The Wall Street Journal, and Bloomberg). In doing so, we made three contributions to the international business literature. Equally importantly, given that the extant IB studies have rarely employed historical accounts to research important IB topics, we deployed unique historical research methods, thus compiling and reconciling empirical evidence relating to US trade protectionism and the reconfiguration of GVCs.

Our findings contribute to the IB, de-globalization, and the GVCs literature in several important ways. First, the IB literature makes the implicit assumption that globalization is relentlessly accelerating. Conversely, our study drew on the de-globalization literature to challenge this implicit assumption. We conceptualized international trade protectionism as a specific form of de-globalization and proposed that it acts as a driver to shape policy reforms and tariffs in order to control the activities of GVCs and spur local economic activities for low-skilled workers, thus leading to the reconfiguration of GVCs from the global to the regional and local scale. Our efforts to identify this link have significant implications for both theory and practice. Our other important contribution to the IB literature is that we took a step toward exploring the potential influence of international trade protectionism on GVCs by taking into account various industries as a boundary condition, as more globalized industries rely far more on global suppliers of components, which certainly poses both more opportunities for and threats to the functioning and coordination of GVCs, an aspect that is virtually neglected in the IB literature. We, therefore, filled this gap in the dominant IB studies.

Second, our study makes important contributions to both the de-globalization and GVCs literature. The de-globalization literature suggests that changes in the global structural and political systems to protect national economies from immigrants have serious implications for IB and the vulnerability of GVCs. Relatedly, the international trade protectionism measures enacted by governments are expected to limit the international transfer of the tacit knowledge that resides in global excellence centers, restrict the free movement of goods and shift production to geographically dispersed locations to reduce costs, and disharmonize those international trade policies that foster inequality and industrial decay. Unfortunately, we lack a systematic understanding of the nature and extent of international trade protectionism and its impact on GVCs. This has been echoed by those scholars who have called for more research on “the potential impact of various expressions of the renewed protectionism, such as Brexit and Trumpism, on GVCs.” Our study hence responds to this call by exploring the potential impacts of trade protectionism on GVCs, with the core argument that trade protectionism poses serious challenges to their activities. It thereby advances the de-globalization literature by not only placing de-globalization in the context of international trade protectionism, which has been little explored but also exploring the consequences of such protectionism.

On the other hand, our study also contributes to the GVCs’ literature, which suggests that a clear pattern of dispersed and fragmented international MNE business activities emerges where offshore production sites located in low-cost developing countries are closely linked with consumers in developed markets. The critical role played by GVCs in international business, alongside the populist and nationalist rhetoric that is emerging from developed markets (e.g., the US), has generated a severe backlash against globalization and the very nature of GVCs due to the disappearance of local companies and firing of workers resulting from increased foreign competition. The global integration of value chain activities is disrupted by import tariffs, anti-globalization policies, and restrictions on the migration of skilled labor for the free flow of ideas and knowledge through GVCs. Institutional changes have reversed the globalization trend, with governments implementing protectionist measures and weakening global institutions such as the World Trade Organization. Globalized industries are increasingly more likely to be severely affected by trade protectionism – in the form of increased tariffs and trade restrictions to reduce imports in an attempt to protect domestic sectors and boost local employment, which limits the trade activities of MNEs and restrains the free flow of goods, services, and capital across borders. This situation has been made more complicated, for example, by the US’s ‘America First’ policy stance, resulting in the initiation of strict industrial policies and tariff wars aimed at curtailing imports from Canada, Mexico, Europe, and China. We advance the GVCs literature by connecting it with the de-globalization literature, which had hitherto been largely viewed as separate despite being closely associated. We synthesize the key insights and establish the link between the two streams of literature, proposing that trade protectionism plays a key role in shaping policy reforms and tariffs in order to control GVC activities and spur local economic activities for low-skilled workers.

Besides contributing to knowledge, our study has practical and policy implications. First, it provides insights to MNEs’ decision-makers about changing global market environment. Given the fact that the trade protectionist measures by governments are increasing trade barriers for MNEs and disrupting GVCs, it is vital for MNEs to consider macro-economic factors including protectionism policies that undoubtedly determine the effectiveness of GVCs. This high-level consideration is particularly relevant for those decision-makers of MNEs who are doing the cost–benefit analysis of developing and nurturing GVCs. The consequence of protectionism having disrupted GVCs is that the over-reliance on global partners affected the operations of MNEs, thereby reducing their profitability. Therefore, decision-makers must determine which activities should be outsourced to global partners and which should be assigned to regional partners. By doing this, MNEs can diversify their outsourcing activities at both regional and global levels, therefore achieving profit gains even during disruptive events. Moreover, this study has important implications for policies and policy-makers. On the one hand, there is an urgency for policies that should reduce trade deficits and cut the import tariff revenue losses suffered by MNEs in order to improve their competitiveness. On the other hand, it is vital for policy-makers to pay greater attention to the populace with low education levels and low skill sets, who are vulnerable to ever-changing job environments, since these marginalized low-skilled workers who forced the de-globalization movement desperately need their governments to take actions by, for instance, creating favorable policies to help and protect them as well as providing them with training opportunities.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Next, we review the literature on GVCs and trade protectionism. We then detail our methodology with an explanation of the data collection and analysis process. Subsequently, we present our findings on how US trade protectionism affects the GVC activities of MNEs. Before concluding, we present the theoretical and practical implications of our study as well as its limitations.

s11575-023-00522-4

To read the full research article as it was published by Springer Nature, click here.

To read the full research article, click here.