The US-China Investment Project clarifies trends and patterns in two-way investment flows between the world’s two largest economies. This report updates the picture with full-year 2018 data and describes the outlook as we move through 2019. The key findings are:

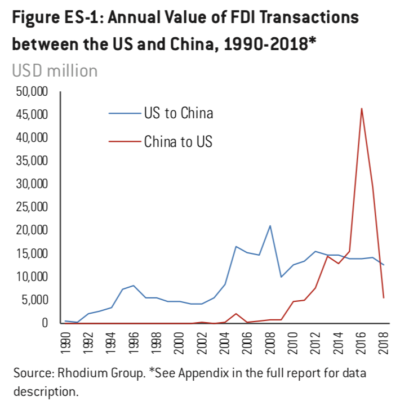

Two-way foreign direct investment (FDI) flows dropped nearly 60% year-over-year in 2018.

- $18 billion of completed two-way FDI between China and the United States (US) in 2018 represented a 60% decline compared to 2017 and a 70% decline compared to the record $60 billion seen in 2016.

- The bulk of this drop was attributable to over 80% decline in Chinese FDI in the US to just $5 billion from $29 billion in 2017 and $46 billion in 2016. Accounting for asset divestitures, net 2018 Chinese FDI in the US was -$8 billion. Meanwhile, American FDI in China dropped only slightly to $13 billion in 2018 from $14 billion in 2017.

- The FDI balance shifted back towards US investors in 2018. After briefly being surpassed by their Chinese counterparts in 2016 and 2017, US firms once again invested more in China last year than Chinese firms did in the US. Cumulative US FDI in China (at historical cost) still exceeds cumulative Chinese FDI in the US by a factor of two ($269 billion vs. $145 billion). Accounting for asset divestitures, exchange rate changes and asset appreciation would further widen this gap.

Regulatory interventions and the deteriorating political relationship were the main culprits behind the sharp decline in two-way FDI.

- Beijing’s outbound direct investment controls and its crackdown on highly leveraged private investors continued to weigh on Chinese FDI in the US. A deliberate tightening of liquidity in China’s financial system further exacerbated headwinds, forcing firms to clean up their balance sheets instead of investing abroad.

- Chinese investors also encountered stepped-up investment screening by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) and uncertainty over the broader US-China political relationship. We estimate that Chinese investors abandoned deals worth more than $2.5 billion in the US in 2018 due to unresolved CFIUS concerns.

- Growing US government concerns about technology leakage also weighed on US direct investment to China, especially in the technology space. And while there are signs that US investors intend to take advantage of widening Chinese market access (for example in autos and financial services), these policies came too late to meaningfully boost 2018 numbers.

Shifting regulatory attitudes and political realities are transforming the industry and investor mixes for two-way FDI.

- Chinese outbound FDI decreased dramatically in some sectors like real estate and hospitality that were blacklisted by Beijing and even turned negative accounting for divestitures. Meanwhile, stepped-up US national security reviews weighed on activity in other sectors including information and communications technology (ICT) and infrastructure. Less impacted by these policy pressures, health and biotech became the top sector for Chinese FDI in the US in 2018.

- China’s domestic crackdown on leveraged outbound investors has dramatically changed the landscape of activity in the US. Several companies that led the Chinese FDI boom in the US since 2014 – including HNA, Anbang and Wanda – have not just stopped new investments but were forced to divest most of their previously acquired assets.

- The chilling impact of politics on US FDI in China was mostly visible in the ICT space where new investment declined significantly last year. In contrast, US investment in China saw growth in consumer-related sectors such as food and entertainment. Real estate assets (which are less security-sensitive and more attractive to financial investors) also drew growing US investor interest. Looking forward, we expect strong growth in sectors with lowered equity ownership restrictions including automotive and financial services.

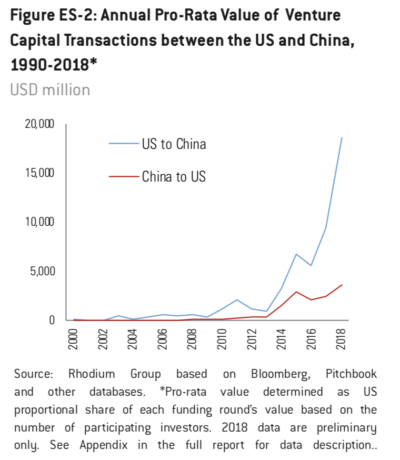

Non-FDI investment flows such as venture capital (VC) have become increasingly important drivers of US-China capital flows and were more resilient than FDI in 2018.

-

- Direct investment flows have historically dominated US-China deal making but other flows have become increasingly important in recent years. Venture capital investment in technology and other start-up companies is one such conduit. At an estimated $22 billion, two-way VC flows surpassed bilateral FDI for the first time in 2018.

- US venture investment in China has a long track record dating back more than two decades. In 2018, US-owned venture companies invested a record $19 billion in Chinese start-up companies– roughly double the previous record of $9.4 billion in 2017 and five times flows in the other direction.

- Barely existent five years ago, Chinese VC investment in the US has soared since 2014 and continued to flourish in 2018, even while FDI investment slowed sharply. Chinese-owned VC funds participated in more than 270 unique US funding rounds in 2018, contributing an estimated $3.6 billion. Chinese venture investment in the US has drawn considerable attention, but it plays a much smaller role in the US venture capital ecosystem than US venture capital investment plays in China’s.

Venture capital patterns show that investors have strong appetite to gain exposure to sectors that are restricted or scrutinized for direct investment.

- Chinese VC in the US remained virtually untouched by investment screeners before November 2018. This allowed investment activity to continue in semiconductors and other areas that recorded sharp drops in direct investment in recent years due to stepped-up investment security reviews.

- In China, American investors continued to utilize minority VC investments in 2018 to gain exposure to sectors that are off limits to full-blown foreign takeovers or have powerful informal market entry barriers, for example, digital payments, internet startups and other digital content.

The political outlook remains fragile, and new policies could further depress commercial appetite for greater FDI and portfolio flows.

- Recent Chinese policy steps including the revised Foreign Investment Law and a narrower FDI negative list are positive for foreign investors, but implementation remains uncertain, and these steps do not represent a grand solution to the outstanding investment frictions and fairness concerns. China is also facing macroeconomic pressures that make it unlikely Beijing will loosen outbound capital controls anytime soon. These controls also remain a major hurdle for foreign firms and portfolio investors (especially those with fiduciary duties).

- In the US, stakeholders are still awaiting the final implementing regulations for new laws (The Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA) and the Export Control Reform Act (ECRA)) that could significantly broaden US regulatory oversight over emerging technologies. These regulations could impact FDI and VC flows alike, and expanded export control rules and greater scrutiny on supply chain risks for government suppliers could also become significant hurdles for American investment and sourcing in China.

A “trade deal” could boost sentiment for two-way investment, but strategic distrust and national security concerns will remain.

- While details surrounding the current US-China negotiations remain vague, reports suggest a deal could include a broad elimination of restrictions on US direct investment in China.

- Any new clarity on the implementation of new investment policies (FIRRMA and ECRA on the US side and the Foreign Investment Law and FDI negative list in China) that accompanies or follows a deal would also create transparency and help restore predictability for investors.

- However, even with moderate FIRRMA and ECRA rules and a reasonable “trade war” outcome (neither of which is assured), US-China economic tension is here to stay. Hawks successfully bolstered their case against overly permissive US policy in 2018, and many changes will not be undone.

- Leaders must manage this reality and find ways to address novel security concerns without too much protection, which would threaten long-term innovative capacity and prosperity.

The rise of more restrictive investment policies in the US-China context has implications for other nations, and the global economy would benefit from a multilateral approach to re-configure investment policy.

- Aggressive US unilateralism and defensive policies towards China are polarizing other members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Some are aligning with US views on Chinese capital flows and general openness. For example, a new European Union (EU) investment screening framework has taken shape since late 2018 that is more concordant with US principles. However, other OECD nations are pushing back, for example by committing to allow Chinese companies to continue supplying equipment to their 5G infrastructure.

- This polarizing approach risks a balkanizing of investment policy across the OECD and has distracted leaders from the essential convergence of their priorities. Numerous important outstand- ing policy questions can be more effectively resolved with cooperation. These policy questions include where to draw the line between legitimate investment security concerns and disguised protectionism; to what extent reciprocity in cross border investment is necessary and should be pursued; and whether and how to use existing institutions such as the World Trade Organization(WTO) and the OECD to address current and future challenges.

The full report and an updated data visualization are available on the re-launched project website, the US-China Investment Hub. This report was published by the Rhodium Group.