The border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland has become a central issue in the Brexit negotiations between the UK and the EU. This column examines the proposals put forward by the two negotiating parties, and suggests two remedies that could make the European Commission’s initial ‘backstop’ proposal, whereby Northern Ireland would remain in the European Customs Union while the rest of the UK would be excluded from it, acceptable to the UK.

Brexit has thrown up many complex questions (Snower and Langhammer 2019); the border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland is one of the most difficult. Indeed, the border has become a central issue in the negotiations on the withdrawal of the UK from the EU. Its complexity rests on the fact that the political elements of the issue are intertwined with the economic ones. With the European Council guidelines of 29 April 2017 for the negotiations with the UK, the EU requested that the border remain open, i.e. with no physical infrastructure and controls, in order to ensure that the 1998 peace agreement (the Good Friday Agreement) continues to be respected and that the economic integration between the North and the South of the island is preserved.

The removal of all security installations at the border, explicitly foreseen by the Good Friday Agreement, has led to a total opening. This is considered a key symbol of the success of the peace process. The restoration of a hard border, introducing a clear and tangible separation between the two countries, would thus be seen as undermining the spirit of the Good Friday Agreement. The EU has an important stake in the peace process, to which it contributes financially through the PEACE programme and the INTERREG initiatives in the area, within the framework of the European Regional Development Fund.

In this column, and in greater detail in a recent paper (Marongiu Buonaiuti and Vergara Caffarelli 2018), we analyse the question of the Irish border in its economic and political implications. We shall then examine the proposals put forward by the two negotiating parties, discussing to what extent each of them can be made ‘practicable’ – i.e. operationally implementable, compatible with the constraints placed by the EU’s legal system and by the WTO rules,1 and politically acceptable to the other party – through specific adjustments, or ‘remedies’. Finally, we discuss the compromise solution included in the Withdrawal Agreement reached by the two parties, approved by the European Council on 25 November 2018.

Northern Ireland’s economic integration with the rest of the UK and with Ireland

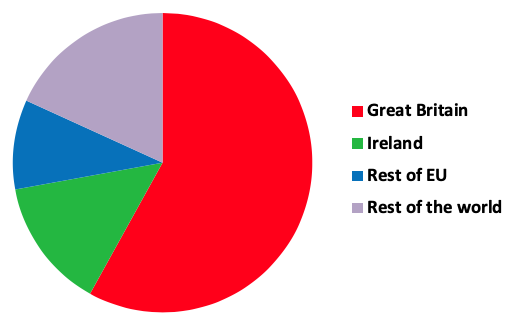

In order to appreciate the degree of economic integration of Northern Ireland with the rest of the UK (i.e. Great Britain) and with the Republic of Ireland, one can look at the trade flows between these economies. The external sales of Northern Ireland (about one third of total sales) are concentrated on the rest of the UK (58%), while the share of sales to Ireland amounts to 14% and that to the rest of the EU to about 10% (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Northern Ireland external sales, 2016

Source: calculations based on data from the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency

However, in order to properly understand the degree of integration between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK, on the one side, and Ireland, on the other, one needs to take into account the different sizes of the partner economies. Gravity analysis (Chaney 2018 and references therein) is a useful tool in this respect, and it shows that international trade between two areas is positively correlated with the GDP of each economy and negatively with their distance. Given the proximity of Northern Ireland with both Ireland and the rest of the UK, it is sufficient to compare the relevant trade to GDP ratios. North-South trade in the island of Ireland is equal to 2.5% of the Irish Republic’s GDP,2 while trade between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK – while higher in absolute terms – amounts to only 1.4% of Great Britain’s GDP. This shows that, once we take into account the relative size of the two economies, Northern Ireland is even more economically integrated with the Republic of Ireland than with the rest of the UK.

The ‘red lines’ set by the EU and the UK during the negotiations

During the negotiations, both the EU and the UK set some constraints (the ‘red lines’), with important implications for the possible solution to the Irish border issue. The EU reiterated the absolute indivisibility of the four fundamental freedoms: free movement of people, goods, services, and capital. The EU also stressed that no third country should be able to enjoy benefits and rights comparable to those of the member states, and excluded any form of sector-by-sector participation to the Internal Market. The point of greatest interest for this study is the already mentioned explicit request to avoid a physical border between Ireland and Northern Ireland, while respecting the integrity of the EU’s legal order. As for the future relations with the UK, the EU specified that any free trade agreement would have to be balanced, ambitious, and far-reaching, and guarantee a level playing field.

The UK Government, for its part, interpreted the result of the referendum held on 23 June 2016 as a request to regain control over borders, laws, and public finances, and therefore attaches a high priority to recovering the ability to define its own policies on international trade and immigration independently of the EU, to leaving the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice and to putting an end to the application of European law in the UK, as well as to no longer contributing to the EU budget. Finally, the UK also declared it did not want a return to “the borders of the past” in the island of Ireland.

During the negotiations two proposals were presented, respectively by the EU and the UK, in order to identify a concrete solution to the problem, but neither was accepted by the other party until the compromise solution reached at the negotiators’ level on 14 November 2018.

The European Commission’s proposal

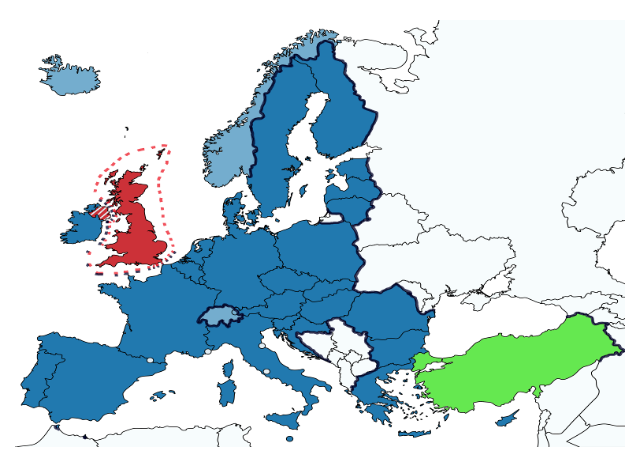

The European Commission had proposed a solution whereby Northern Ireland, unlike the rest of the UK, would remain in the European Customs Union and continue to be subject to a large part of the Single Market rules, while the rest of the UK would be excluded from it (Figure 2). The EU proposal was not meant to be the final solution to the border problem, but only a ‘backstop’ that would become operational unless and until a more satisfying solution was reached in the negotiations on the future bilateral relationships.

Figure 2 The European Commission’s proposal

Note: The EU customs border, which includes Turkey and Northern Ireland, is highlighted in blue, the British in red; the EU customs union includes the Member States (in blue), Andorra, San Marino, the Principality of Monaco and the Vatican (all in light blue), and Northern Ireland (in red and light blue); Turkey (in green) has a separate customs agreement with the EU.

The UK’s proposal

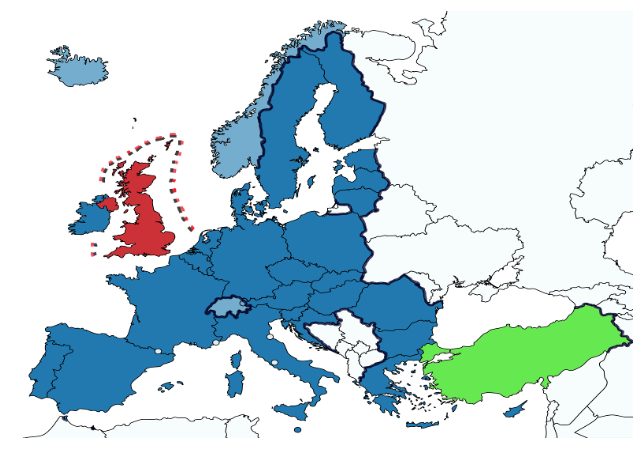

The British government proposed, instead, the shift of the European customs border to coincide with the British external border through the creation of a free trade area encompassing both the EU and the UK, in order to ensure that no further control would need to be carried out between the UK and the EU (Figure 3).

Figure 3 The UK’s proposal

Note: The EU customs border, which includes Turkey, is highlighted in blue, the British one in red; the EU customs union includes the Member States (in blue), Andorra, San Marino, the Principality of Monaco and the Vatican (all in light blue); Turkey (in green) has a separate customs agreement with the EU.

The EU proposal was viewed as unacceptable from the UK’s standpoint on the grounds that it would allegedly compromise the constitutional unity of the country, as well as the integrity of the UK’s internal market. The British proposal was in turn felt to be unacceptable by the EU side because it would have implied a delegation of the implementation of the EU customs policy to a non-member state, and the free trade area advocated by the UK was held to amount to de facto UK participation in the Internal Market for goods only. The sole point shared by the two parties was their commitment to maintaining the Common Travel Area between Ireland and the UK.

We now turn to the conceivable remedies that could be put in place to overcome the objections raised to each of the two proposals in their initial formulation. Starting from the EU proposal, the latter could be complemented with two remedies in order to meet British concerns: a) the UK could waive tariffs and customs checks on imports from the Northern Ireland, and b) Northern Ireland companies could be granted a reimbursement of the EU tariffs paid on goods imported from Great Britain and intended for local consumption. In this way, Northern Ireland would not be economically isolated from the rest of the UK.

As concerns the British proposal, remedies could be found in order to avoid the need for the EU to delegate the implementation of its customs policy to a non-member state by allowing customs checks upon entry to the UK to be carried out jointly by British and EU customs officers, each for their ‘own’ imports. The implementation of the EU policy would then be performed by EU agents and not by UK ones. Other issues raised by the British proposal, however, appear to be more difficult to solve, because they interfere with the fundamental EU legal principle of the indivisibility of the four freedoms and of the Internal Market.

Compatibility of either proposal with EU law and the WTO’s legal framework

From the legal point of view, we need to assess the compatibility of both proposals and their respective remedies with European and international law, with particular regard to the regulatory framework of the WTO.

The EU proposal appears indeed compatible with EU law, since it implies relying on legal tools already familiar in the handling of trade relations with neighbouring third countries (Pérez Crespo 2017). It would also be compatible with WTO rules, since the inclusion of Northern Ireland in the EU Customs Union would appear consistent with the frontier trade exception provided for under Article XXIV, para. 3, lit. a), GATT 1994, and hence it would not trigger the application of the most-favoured nation clause in respect of the EU (Sacerdoti 2018). As concerns the remedies intended to make it acceptable to the UK side, a UK waiver on tariffs and customs checks on imports from Northern Ireland could be analogously considered as supporting frontier trade, while it would not raise significant problems under EU law. The reimbursement of the EU tariffs paid by Northern Irish importers on British goods intended for local consumption would not be an issue under the WTO legal framework, while it might be considered state aid under EU law. Yet, even conceding that the reimbursement of tariffs that were essentially not due might qualify as state aid, there are exceptions under Article 107, para. 3, TFEU, allowing for state aid measures if these aim at supporting the development of a given economic area, such as both the Irish and the Northern Irish economies (lit. c), or at remedying serious economic disturbances (lit. b).

The UK proposal, in turn, would appear compatible with WTO law, since it was based on the establishment of a free trade area (Article XXIV, para. 5, GATT 1994), but it would de facto amount to total freedom of movement of goods between the UK and the EU, separating this from the other three fundamental freedoms. The (partial) remedy consisting of joint EU-UK customs checks at the UK border would be compatible with both EU and WTO rules, but it would not suffice to make the overall UK proposal acceptable in terms of compatibility with the EU legal framework, with particular regard to the indivisibility of the four fundamental freedoms and of the Single Market.3

The compromise solution embodied in the Withdrawal Agreement

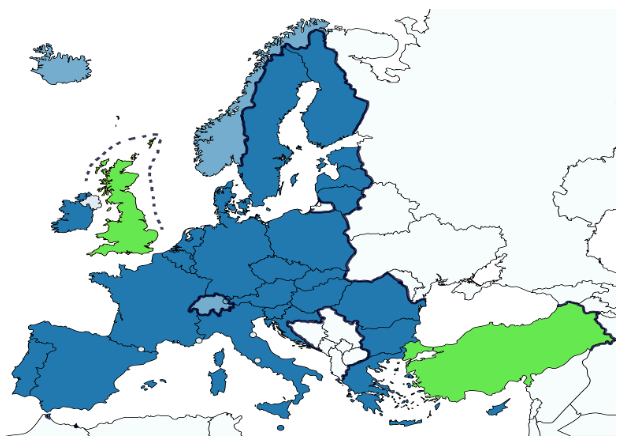

Finally, a compromise solution was written into the Withdrawal Agreement as defined at the negotiators’ level on 14 November 2018. Such a solution is intended as a backstop and provides for the conclusion of a customs agreement between the EU and the UK, establishing a ‘single customs territory’ within which the degree of regulatory alignment of Northern Ireland to the EU will have to be greater than that for the rest of the UK. In fact, this solution corresponds to the initial EU proposal, combined with a customs agreement between the EU and the rest of the UK, which avoids the mutual imposition of tariffs (Figure 4) and reduces the amount of customs controls between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK, limiting them to regulatory checks.

Figure 4 The compromise solution

Note: The EU customs border, which includes Turkey and the UK, is highlighted in blue; the EU customs union includes the Member States (in blue), Andorra, San Marino, the Principality of Monaco and the Vatican (all in light blue); Turkey and Great Britain (in green) have separate customs agreements with the EU.

This solution binds, for the indefinite time necessary for the definition of the framework of future UK-EU relationships, the UK’s trade policy to that of the EU, thereby inevitably putting off the achievement of full and effective UK ‘independence’ in trade policy. It is precisely these non-negligible limitations to the achievement of the advocated autonomy in the field of foreign trade that appear to be at the origin of the strong resistance to the agreement that has arisen in the domestic political debate, and that eventually led to the rejection of the Withdrawal Agreement by the British Parliament.

The current impasse and possible way out

Following that rejection, the negotiation has reached an impasse. The Irish backstop, which is an integral part of the Withdrawal Agreement, is not acceptable to the majority of the British Parliament, which has mandated the government to renegotiate it. Yet the EU has indicated its unwillingness to reopen negotiations on the agreement, although the political declaration on the future relationship could be renegotiated if there is a material change in the UK’s ‘red lines’. In this context, a variety of scenarios could arise.

The initial EU proposal for the Irish backstop could be a key element of a successful agreement on the future relationships between the EU and the UK. If combined with the remedies discussed above, that proposal could perhaps be more acceptable to a majority of the British Parliament than the current backstop incorporated in the Withdrawal Agreement, and prevent it from ever coming into force. In fact, those remedies would guarantee that the Irish border will remain open and ensure the economic integration of Northern Ireland with the rest of the UK (at least as effectively as the ‘single customs territory’ envisaged by the Agreement), while the UK would be granted the desired autonomy in its trade policy. For the same reasons, were negotiations on the Withdrawal Agreement eventually to be reopened, it might be worthwhile replacing the current Irish backstop with the initial EU proposal.

Authors’ note: The opinions expressed in this column are the authors’ own and not those of the Bank of Italy. We are grateful to Pietro Catte, Carlo Curti Gialdino, Andrea Finicelli, Maurizio Ghirga, Ruggero Ippolito and Susana Sanchez Moreno for helpful comments. The usual disclaimer applies.

References

Chaney, T (2018), “The gravity equation in international trade: an explanation”, Journal of Political Economy 126(1): 150-177.

Cremona, M (2017), “UK Trade Policy”, in M Dougan (ed.), The UK after Brexit. Legal and Policy Challenges, Intersentia, pp. 247-265.

De Witte, B (2018), “An Undivided Union? Differentiated Integration in Post-Brexit Times”, Common Market Law Review 55: 227-250.

Marongiu Buonaiuti, F and F Vergara Caffarelli (2018), “La Brexit e la questione del confine irlandese”, Federalismi.it 24: 1-34.

Pérez Crespo, M J (2017), “After Brexit… The Best of Both Worlds? Rebutting the Norwegian and Swiss Models as Long-Term Options for the UK”, Yearbook of European Law 36 (1): 94-122.

Sacerdoti, G (2018), “Il regime degli scambi del Regno Unito con l’Unione europea e i paesi terzi dopo la Brexit: opzioni e vincoli internazionali”, Rivista di diritto internazionale 101: 685-714.

Snower, D and R Langhammer (2019), “Untangling Brexit”, VoxEU.org, 7 January.

Tedeschi, R (2018), “The Irish GDP in 2016. After the disaster, we are in a dilemma”, Questioni di Economia e Finanza 471, Bank of Italy, pp. 1-30.

Weatherill, S (2017), “The Several Internal Markets”, Yearbook of European Law 36(1): 125-178.

Endnotes

[1] For a general discussion of the relevant legal framework, see Cremona (2017).

[2] If one replaces Ireland’s GDP with the GNI*, a measure of national income for Ireland released by the Central Statistics Office that excludes globalisation effects that are disproportionally impacting the measurement of the Irish economy (Tedeschi 2018), the ratio becomes 3.8%.

[3] See Weatherill (2017), and also De Witte (2018) questioning the pertinence of this principle.

[To read the original article, click here.]

Copyright © 2019 VoxEU. All rights reserved.