Argentina is grappling with a serious economic crisis. Its currency, the peso, has lost two-thirds of its value since 2018; inflation is hovering around 30%; and since 2015 the economy has contracted by about 4% and its external debt has increased by 60%. In June 2018, the Argentine government turned to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for support and currently has a $57 billion IMF program, the largest program (in dollar terms) in IMF history. Despite these resources, the government in late August and early September 2019 postponed payments on some of its debts and imposed currency controls. The outcome of the presidential election on October 27, 2019, which pits current center-right President Mauricio Macri against the center-left Peronist ticket of Alberto Fernández for president and former President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner for vice president, will shape Argentina’s policy response to the economic crisis.

Economic Crisis in Argentina

Argentina has a long history of economic crises. It has defaulted on its external debt (debt held by foreigners) nine times since independence in 1816. Argentina has also entered into 21 IMF programs since joining the international organization in 1956. The current economic crisis facing Argentina stems from longstanding challenges, as well as more recent developments.

Economic Reforms but Growing Vulnerabilities

When President Macri was elected in 2015, he ushered in a series of economic reforms aimed to address the unsuccessful economic policies of the previous Kirchner governments, which had governed Argentina since 2003. He cut export taxes, lifted currency controls, and resolved a 15-year long dispute with holders of defaulted Argentine bonds, allowing Argentina to resume access to international capital markets. The central bank also raised interest rates to 25% to curb inflation. The economy contracted by 1.8% in 2016, but resumed growth of 2.9% in 2017. To maintain political support for the reforms and support the country’s most vulnerable (one in three Argentines was living below the official poverty line in 2015), the government held off on substantial fiscal reforms to address the budget deficit, 4.3% of GDP in 2014.

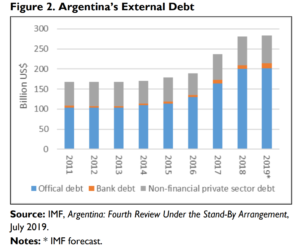

However, the Macri government saw borrowing costs rise, as it switched to traditional borrowing from international capital markets relative to the Kirchners’ unorthodox financing tools, including money creation and coercing domestic banks into buying government bonds. The Macri government issued $56 billion in external debt between January 2016 and June 2018. Interest payments facing the government caused the budget deficit to increase to 6.4% of GDP in 2017. Meanwhile, capital inflows into the country to finance the deficit contributed to an overvaluation of the peso, by 10-25%. This overvaluation also exacerbated Argentina’s current account deficit (a broad measure of the trade balance), which increased from 2.7% of GDP in 2016 to 4.8% of GDP in 2017.

Crisis and Initial Policy Response

Argentina’s increasing reliance on external financing to fund its budget and current account deficits left it vulnerable to changes in the cost or availability of financing. Starting in late 2017, a number of factors began to create problems: the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) began raising interest rates, reducing investor interest in Argentine bonds; the Argentine central bank reset its inflation targets, raising questions about its independence and commitment to lower inflation; and the worst drought in Argentina in 50 years hurt commodity yields, significantly eroding agricultural export revenue.

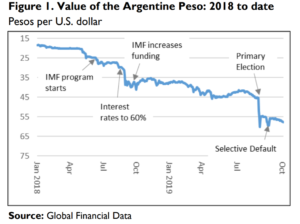

Investors began selling Argentine assets, putting downward pressure on the peso (Figure 1). With most of its debt denominated in dollars, a depreciated peso increased the value of the debt in terms of pesos. To improve investor confidence, the central bank and government announced in April and May 2018 higher interest rates (to 40%) and fiscal reforms to cut the budget deficit. Market volatility continued, however, and in June 2018, the Macri government reached an agreement with the IMF for a three-year, $50 billion program. The government received $15 billion from the IMF upfront, with the intention to treat the remainder of the program as precautionary (having the resources available but to not actually to draw on them).

At the program’s outset, skeptics raised questions about the fiscal cuts and growth projections underpinning the program. Through the program, the government committed to politically unpopular austerity measures to bring the primary deficit (the government budget, excluding interest payments) into balance by 2020, from 3.8% of GDP in 2017. The IMF was aware of the potential risks when the program was approved in June. IMF staff noted in program documents they could not certify under the baseline forecast scenario with a high probability that Argentina’s debt would be sustainable. Argentina’s external debt is currently projected to reach $285 billion in 2019, an increase of more than $100 billion since 2015 (Figure 2).

Despite an infusion of funds from the IMF and commitments on fiscal reforms, the peso continued to depreciate over subsequent months, and the government announced aggressive policies to stabilize the peso. The central bank raised interest rates to 60% in late August 2018, the highest in the world, and the government committed to hastening the pace of fiscal reforms. President Macri requested the IMF accelerate disbursements of its financing. In September 2018, the IMF increased the program to $57 billion and agreed to front-load disbursements of financing, roughly doubling the amount available in 2018 and 2019.

Developments in 2019

The Macri government pursued fiscal reforms, reducing the budget deficit from 5.3% in 2018 to an estimated 2.5% in 2019, and the IMF disbursed funds to Argentina in March and July 2018. The current account deficit also narrowed, from 5.2% in 2018 to an estimated 2.0% in 2019. However, Argentina’s economy contracted by 1.2% in 2019, whereas the IMF program initially envisioned a return to growth in 2019. Austerity measures and high interest rates likely contributed to the economic contraction. The peso’s devaluation made it hard to tame inflation, estimated at 30% in 2019, and increased the real value of Argentina’s debt (mostly denominated in dollars), forecast at 76% of GDP in 2019.

The austerity measures and lingering recession in Argentina eroded Macri’s political popularity. In the August 2019 primary election (which combined candidates from all parties), Macri lost decisively to the Fernández-Fernández ticket. Fernández has pledged to “rework” Argentina’s IMF program if elected; many investors fear that a FernándezFernández government would resume the unorthodox economic policies from the Kirchner years. Following the primary, capital flight from Argentina accelerated, the peso reached a record low, and Argentina’s stock markets dropped.

President Macri subsequently shifted his economic policy approach. The Economy Minister Nicolas Dujovne, who negotiated the IMF deal, resigned on August 17, 2019, and the government rolled out plans for tax breaks, minimum wage increases, and freezing fuel prices. In late August 2019, the government announced it would postpone $7 billion in payments on short-term local bonds while pushing for a maturity extension of $50 billion in longer-term debt mostly held by foreign investors. The government is also seeking to delay repayment of $44 billion of IMF loans. On September 1, 2019, the government, unable to stabilize the peso with high interest rates and sales of foreign exchange reserves, authorized currency controls. Many of these policies are at odds with economic policies pursued by Macri upon his election in 2015.

Economic Implications for the U.S.

U.S. economic exposure to Argentina through direct trade, investment, and financial channels is relatively limited. Some U.S. investors, however, could be affected if the Argentine government seeks to restructure its debt. The role of the IMF also has implications for the United States, the IMF’s largest shareholder. Argentina has historically been a frequent IMF borrower, and previous programs have encountered difficulties. Argentina’s default in 2001, while on a sizeable IMF program, led the IMF to substantially revise its lending policies. In 2018, the U.S. government strongly supported the IMF program for Argentina, given President Macri’s demonstrated commitment to improving U.S.-Argentine relations and reforming its economy. U.S. government views, however, could change if Fernández wins the election and takes an aggressive position against the IMF.

Oversight Questions for Congress

- The Macri government made tough policy decisions, including austerity measures and high interest rates. What more could or should the Argentine government or IMF do to stabilize the economy?

- Argentina has been on IMF programs for more than half the years it has belonged to the institution. In what ways is the current IMF program similar to and different from previous IMF programs for Argentina? Should the United States support an extension of the repayment period for IMF loans to Argentina?

- Should the IMF have required debt restructuring with private creditors before extending the program to Argentina? What risks does Argentina’s program pose to U.S. financial commitments at the IMF?

- Are U.S. financial institutions sufficiently capitalized and diversified to withstand a potential debt restructuring by Argentina? Which U.S. investors would be affected by an Argentine debt restructuring?

For more on Argentina, see CRS In Focus IF10932, Argentina: An Overview, by Mark P. Sullivan.

CRS ArgentinaTo read original report, click here