In last week’s State of the Union address, President Biden made several remarks to the effect that government procurement policy should be directed toward forcing, or at least strongly pushing, businesses to locate goods production in America. He means it too. One of his first Executive Orders was aimed at tightening Buy American regulations. Buy American provisions sound great. They evoke an imagery of patriotism and economic solidarity. If there were a policy version of apple pie, this would be it. The problem is that for all the warm fuzzies these policies are aimed at eliciting, they are actually a lot more counterproductive than most people realize. There is a lot economic frustration right now, particularly around inflation, and that’s fair, but these kinds of policies actually make the problem worse, not better, and it’s important to point out when emotionally attractive policies are unhelpful.

What Buy American Provisions Are

Buy America provisions require the federal government to give an advantage to domestic suppliers in government contracting. In other words, when the government decides how to spend taxpayers’ dollars, it is required to favor American businesses and American products. These provisions first appeared in the Herbert Hoover administration and went along with other protectionist measures like the Smoot-Hawley tariffs to fight the Great Depression. That bundle of beggar-thy-neighbor protectionism is generally seen today as worsening rather than alleviating the Great Depression. While other protectionist policies were abandoned over time, the Buy America provisions have survived in various forms ever since and have recently been favored by Presidents of both parties. President Trump frequently bragged about his expansion of Buy American provisions as part of his broader attack on international commerce. President Biden has, if anything, tried to outbid Trump on this issue. The major thrust of that Executive Order that I mentioned earlier was in its rules on content and waivers. Previously, only half of a product’s value needed to be U.S.-made to count and it was not terribly difficult to get a waiver. The Executive Order tightened the rules on measuring value and on granting waivers. Just last week, the Biden administration once again increased the regulatory threshold on content. President Biden’s left-wing nationalism may be less abrasively expressed than Trump’s America First rhetoric, but it’s still economic nationalism and is no less harmful because it gets served with progressive rhetorical accoutrements.

Why Buy American Provisions are Bad

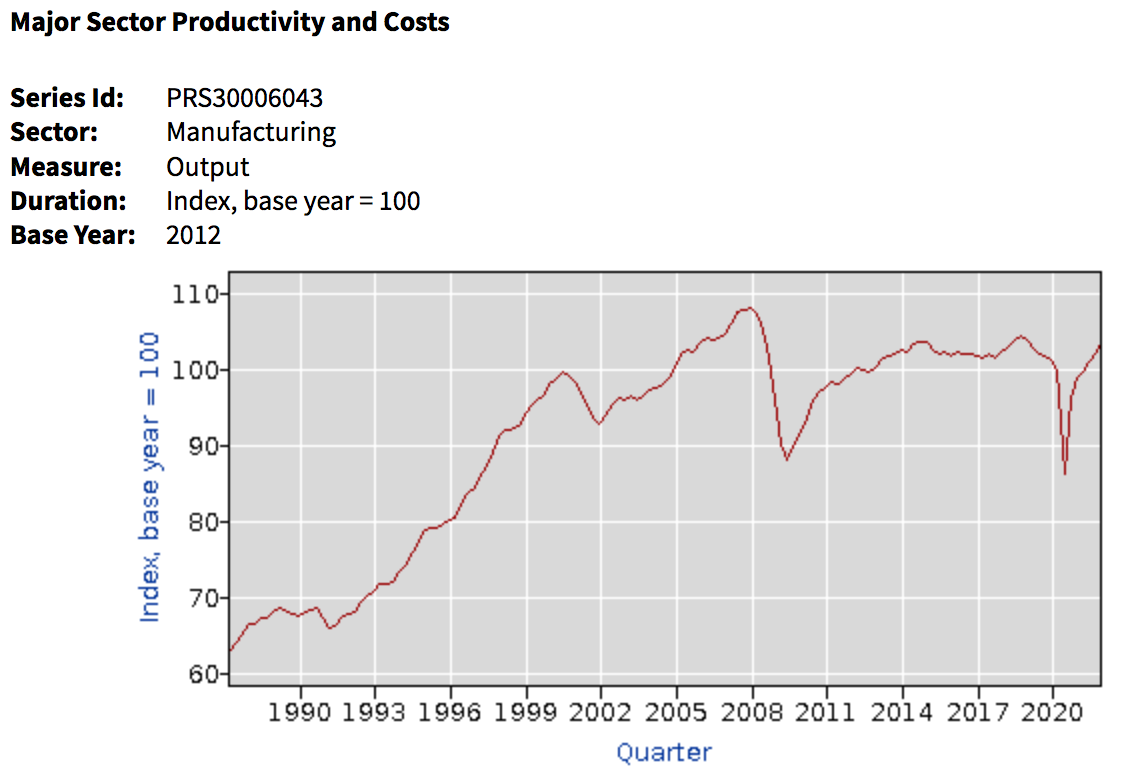

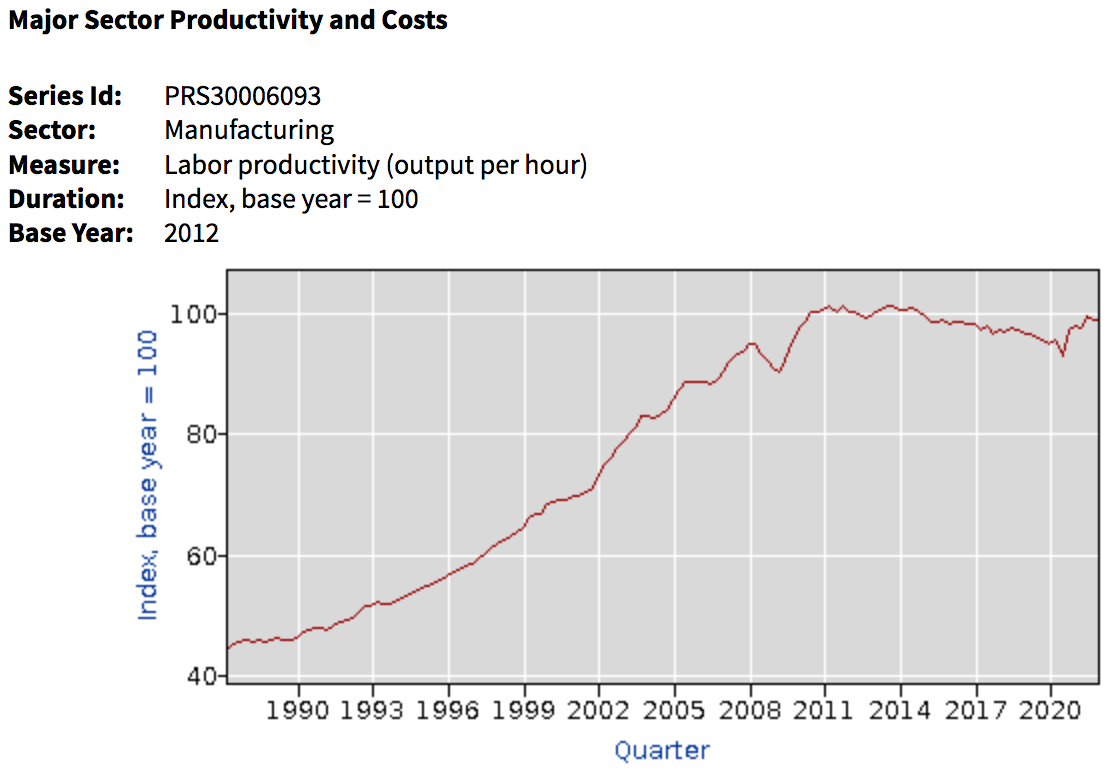

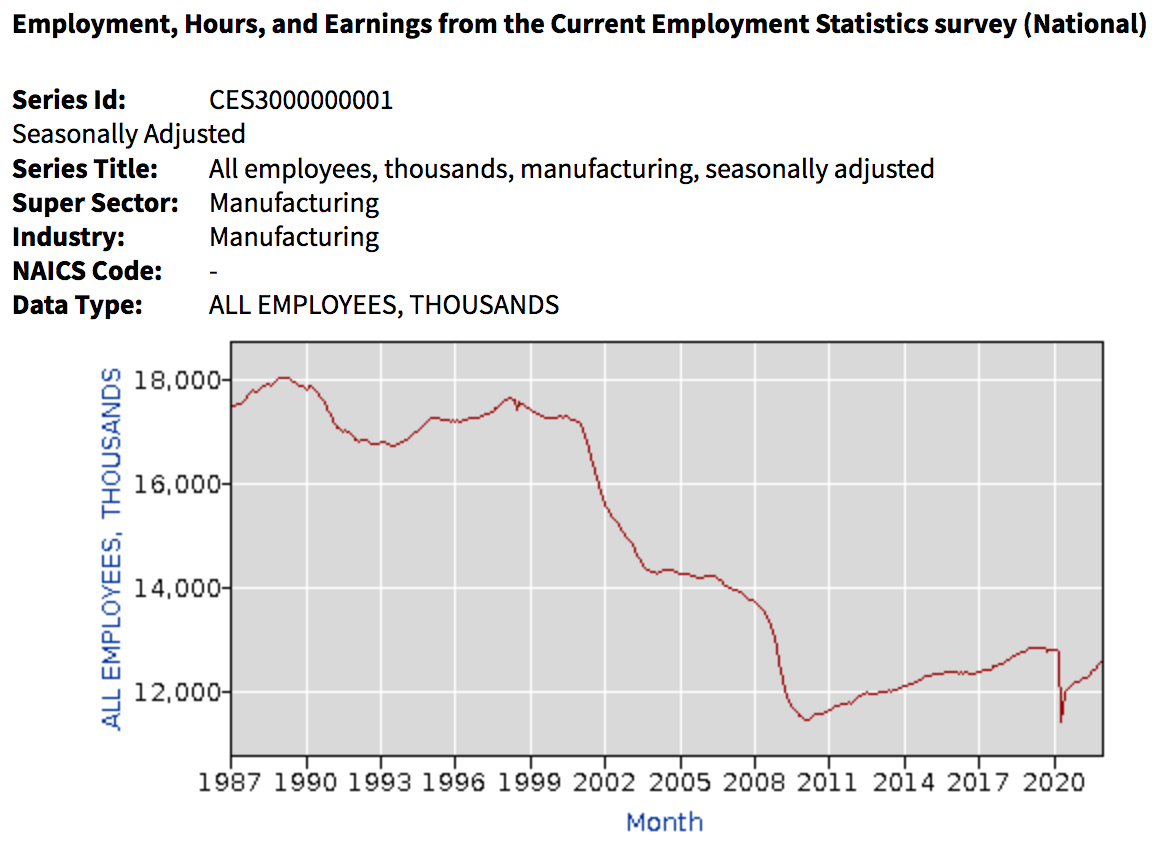

At a practical level, these regulations cause more problems than they solve. The Executive Order is in some ways representative of Biden’s broader protectionism and manufacturing-oriented economic nostalgia. But the ostensible purpose of the EO, i.e. “to save American manufacturing”, is addressing a problem that does not even exist. Manufacturing isn’t suffering. It’s manufacturing employment that is down. As you can see from these charts, output and productivity both rose in the 1990s and 2000s and have held steady since but the number of jobs in manufacturing has fallen from roughly 18 million to roughly 12 million.

That 90s and 2000s’ rise in output and productivity was due to a burst of productivity-enhancing automation. That automation also ate a lot of jobs. Most manufacturing job losses, especially outside of textiles and furniture, is related to automation, not trade. Buy American provisions don’t do anything about that. So, in an important sense, the origin of Biden’s Buy American stance is a fundamental misdiagnosis of what has driven the decline in manufacturing jobs. Indeed, the whole intellectual construct behind much of the rhetoric around Buy American provisions- i.e. that policies like these will recreate the halcyon days of yore with lots of manufacturing jobs- is misguided smokestack chasing. The challenge is not in how to bring back the 1970s but how to help us all prepare for tomorrow.

Buy American rules aren’t just off-base, they are actively harmful. By driving up input costs for businesses and encouraging other countries to retaliate with their own discriminatory procurement policies, they destroy hundreds of thousands of jobs. This is critical to underline. The rules are promoted as a pro-jobs policy but they are, in reality, job killers. When you think of Buy American rules- you should think of policies that both raise costs and kill jobs.

Buy America provisions also drive up costs for government projects. Let’s say that Minneapolis wants to expand its light-rail system to promote mass transit and combat climate change. Buy America provisions force it to buy U.S.-made trains even if Japanese trains are better and cheaper. These costs add up. By one estimate, they are the equivalent of a 25 percent tariff on federal purchases and 10 percent on state-level purchases. Progressives generally want there to be more public goods. Making those goods cost more than they need to directly undermines the goal of providing more of them. Matthew Yglesias succinctly summarizes the problem here; the point of procurement is “quality service provision, not make-work jobs.”

Americans also generally want government spending to be as efficient as possible. Enacting rules that force government to pay 25 percent more for goods and services than it needs to runs directly counter to that, and the numbers on this are not small. According to one estimate, Buy American cost taxpayers $94 billion in 2017 alone.

On top of all that, these provisions do not tend to actually lead to companies choosing to re-shore, which is their ostensible purpose. Finally, the notion that Buy American provisions or any form of protectionism is a way to fight inflation is pure malarkey. Buy American rules quite literally push prices up. It’s just bank-shot rhetorical nonsense to argue that Buy American rules will lead to reshoring and that then will make prices go down. If reshoring were a way to cut costs, companies would already be doing that- without the Buy American rules.

These Buy America provisions, like much other protectionism, are often ostensibly aimed at China, but mostly end up hitting Canada and our European allies. That doesn’t help build an international coalition to respond to the rise of an illiberal China and a reckless Russia. Trade promotion and international interconnection isn’t just about efficiency. It’s about tying countries together to promote peace, interdependence, and cultural exchange. The construction of the US-led liberal international order is one of the great achievements of the 20th century. Buy American provisions are thus not just counterproductive policies, they are also antithetical to the liberal internationalism that progressives ought to value.

So, in sum, Buy American provisions raise government’s and business’ costs unnecessarily, solve a problem that doesn’t exist (manufacturing decline), don’t help with the problem that does exist (inflation), kill jobs, encourage retaliation, and undermine our alliances.

Broader Pathologies

The underappreciated drawbacks of Buy America provisions underscore two broader pathologies in our political culture: a militant aversion to owning up to tradeoffs, and aesthetic-driven policymaking. Biden wants to be a pro-labor union president and, at the same time, his chief economic problem is inflation. Rather than accept that there is some tension between those two goals, his response has been to insist, against all economic logic, that there is in fact no tradeoff between them. With a straight face, he actually said businesses should “lower their costs, not wages” as if somehow wages are not an important component of a firm’s costs. It would be one thing to say that manufacturing jobs are so important that we ought to accept higher costs as a tradeoff for those jobs (setting aside the earlier points about re-shoring and job killing). It is quite another to insist that economic gravity doesn’t apply simply because one doesn’t want it to. That unblinking populist insistence that tradeoffs do not exist is possibly why Buy American provisions poll so well. The way Biden makes it sound, Buy American rules are a ‘free lunch for Americans’ policy- with the billed footed by corporations and foreigners. Unsurprisingly, free lunch on someone else’s dime polls really well! But in reality, it is not on someone else’s dime, it is Americans who pay that lunch tab.

A second pathology is the instinct, common on parts of both the right and the left, to manipulate markets so as to deliver economic benefits to groups associated with favored cultural aesthetics. That is, rather than the state directly providing assistance to those groups or allowing the market to function unimpeded, the state is called on to tinker with the market so as to channel economic benefits toward that favored group. At a philosophical level, that seems unobjectionable, but in practice that brings along two big problems. The first is the way in which some groups, whether that’s unions for economic leftists or culturally extolled professions like coal miners for populist nationalists, get showered with policy goodies while everyone else gets left out and gets to pay higher prices. That’s cronyism by another name.

The second problem is that optimizing policy based not on how it performs but how it sounds as a slogan makes it very easy to overlook the ways in which those policies can do more harm than good. That’s bad. It should be the aim of government to help people, not to pretend to help them while actually hurting them. Buy American provisions are thus akin to patting a worker on the back while you steal twenty dollars from his wallet. That’s the exact kind of behavior we all expect from Donald Trump, but Joe Biden should be better than that.

Part of the reason that Buy American provisions garner political backing is that they combine the right’s penchant for jingoism with the left’s penchant for rules proliferation. Neither of those instincts are helpful in a broader sense and both are driving this specific unhelpful policy. Progressives ought to push back against the jingoism inherent to Buy American rules while libertarians ought to push back against the unnecessary rules-proliferation they represent. Both groups should be relentlessly pointing out the extent these policies do not work as advertised and the extent to which they cause other problems. By doing that, a libertarian-progressive perspective helps guide the way to better policy rather than bad policy that happens to make for a better slogan.

Gary Winslett is an Assistant Professor professor at Middlebury College and the Editor of the LP Papers.

To read the full commentary from The Libertarian-Progressive Papers, please click here.