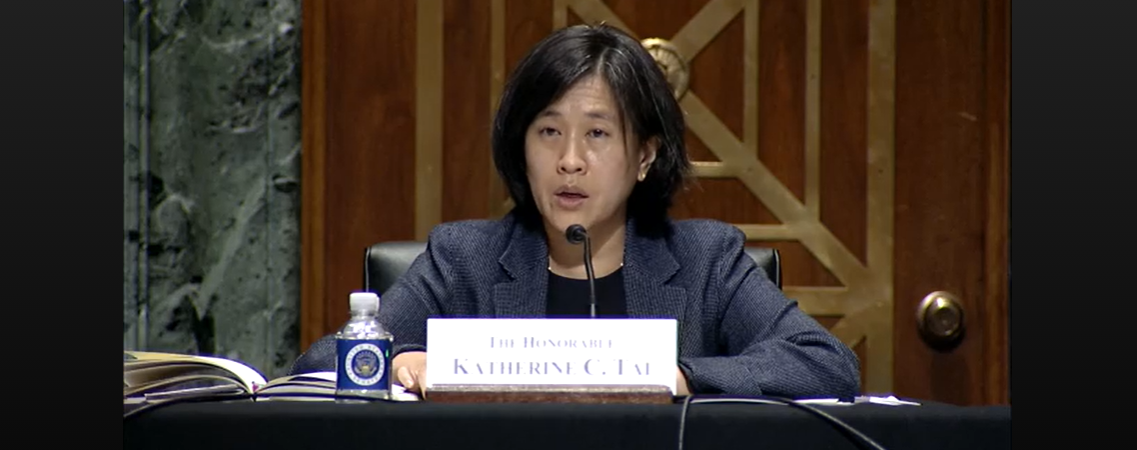

CSIS was privileged last week to host U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) Katherine Tai as she explained the Biden administration’s trade policy on China, and I was happy to have the opportunity to have a conversation with her after her remarks. However, my happiness was tempered by the fact that she very skillfully avoided answering most of my questions. We learned that she has lots of tools for dealing with China, none of which she specified, and that how she proceeds will be influenced by how future discussions with her Chinese counterpart, presumably Vice Premier Liu He, proceed. She was vague on when the next meeting would occur, although since it happened only four days later, I don’t think it would have killed her to let us know it was imminent. She announced that the tariff exclusion process would resume, which it did via a USTR announcement the next day. It seems that when she says something is going to happen, it does—quite quickly. No trial balloons here.

As for the overall thrust of her remarks, judging from the Twitterverse, most listeners were left confused. She seemed to be saying simultaneously that the United States is going to continue to press China on its non-market policies that hurt U.S. companies and workers but that she doesn’t have great hopes for success in persuading the Chinese to change policies. That leads to the obvious question, which she also did not answer: Why are we embarking on a path that we do not expect to lead anywhere?

The question of how the United States will craft its approach toward China was also left vague. The plan does not appear to include a “phase two,” as former president Trump had promised (or threatened), and she did not announce opening a new Section 301 investigation that had been rumored, although she also did not say she was not going to do it. That was a bit surprising, since imposing new tariffs would probably require a new legal basis for doing so, which would mean Section 301 or possibly Section 232, the national security provision.

As a result, my conclusion was that the administration’s policy, at least in the short term, will be enforcement of Trump’s phase one deal. This is ironic, since the question I am asked the most about the administration’s China policy is how it is different from Trump’s. The answer now appears to be not by much.

Ambassador Tai alluded to a number of areas where China had not met its phase one commitments, although she declined to name any particular ones. Several days earlier, Agriculture Secretary Vilsack went a bit further and said that China had met 50 of its 57 agriculture commitments, suggesting that there were seven left to work on, which he did not specify. My friends in the business community tell me that the two biggest specific commitments that remain unmet are disputes over polysilicon and U.S. credit card companies operating in China. And, of course, Chinese purchases of U.S. products clearly lag behind their commitments. Since they have until the end of the year to meet their obligations, it is a bit soon to announce their failure, although in some sectors, like energy, it appears impossible for them to catch up. In others, particularly agriculture, they will come closer.

So, there is plenty to talk about with Liu He, but the important issues like subsidies, forced technology transfer, intellectual property theft, and favorable treatment for state-owned enterprises remain hanging out there unaddressed. Ambassador Tai’s answer to that remains the best one—the administration is engaged in making the United States “run faster” to better compete with China, not so much there but in third markets around the world where the playing field is more level. At the same time, the United States has an important role to play in defending the rules-based trading system. China, having signed up for the rules in joining the World Trade Organization, is fair game when it cheats. The administration is also under pressure from both parties in Congress to take a hard line on China. Eventually it will have to come up with more than it has so far on the so-called “phase two” issues.

In that regard, Ambassador Tai came up with two phrases we no doubt are going to hear frequently—“durable coexistence” and “recoupling.” I have no idea what the first one means. It’s probably better than the Cold War chestnut “peaceful coexistence,” but it may end up meaning the same thing. “Recoupling” is a way of denying that the administration is pursuing decoupling, and for that reason it might provide some rhetorical reassurance to the business community, but actions like threatened reviews of outbound investment, rejections of most Chinese inbound investment, more tariffs, and efforts to promote reshoring in the name of national security will have a much bigger impact on business than statements about recoupling.

So, do we have a policy? In outline, yes, but there is a lot more detail to be filled in before we will really know where the administration is going.

William Reinsch holds the Scholl Chair in International Business at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C.

To read the full commentary from the Center for Strategic & International Studies, please click here.