As foreign direct investment (FDI) in developing countries tumbles to 25-year lows, Least Developed Countries (LDCs) have an opportunity to buck this trend by dismantling trade barriers and developing stable policies that incentivize and de-risk value-add investment into strategic sectors.

Least Developed Countries (LDCs) are missing out on the foreign direct investment (FDI) they need to transform their economies and benefit from meaningful progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). But it doesn’t have to be this way.

According to the 27th Global Trade Alert Report, Advancing Sustainable Development with FDI: why policy must be reset, an annual average of only two new greenfield FDI projects in SDG-intensive sectors were announced in each LDC between 2015 and 2019.

This comes amid broader declines in the real value of FDI into developing countries that started with the 2008 financial crisis and have accelerated during the pandemic.

Although global FDI inflows had been nominally recovering since 2010, gaining an average 7.1% per year until 2019, a typical annual capital depreciation rate of 3.9% eroded much of that growth. At that rate, FDI inflows into developing countries would need to exceed $440 billion just to replace ageing FDI assets. And due to economic fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic, FDI has since plungedto levels not seen since 1995, the report highlights.

This is concerning for LDCs that have yet to replicate the huge economic boost that transition economies and low and middle income countries (LMICs) in East Asia and Eastern Europe had already enjoyed due to FDI, noted Simon Evenett, co-author of the report and Professor of International Trade and Economic Development at the University of St Gallen.

But with creative thinking and support from donors and international organizations, LDCs still have an opportunity to buck the current trend and experience a similar uplift, he added. “Just because it hasn’t happened to the degree LDCs might have liked in the past doesn’t mean it won’t happen in the future.”

Facilitate commercial returns

One lesson LDCs can apply from recent years is that facilitating good commercial outcomes for FDI investors is critical.

Despite the higher risks associated with investing in developing countries – and hence investors’ rational desire to be compensated with higher returns – direct foreign investments in developing countries in Asia Pacific and Central and South America have for more than a decade yielded returns that barely exceed those of European Union countries, the Global Trade Alert Report noted.

According to UNCTAD’s 2020 World Investment Report, the fall in global FDI inflows coincides almost exactly with a gradual decline in those investments’ financial returns, which shrank from 7.1% in 2010 to 6.7% by 2019. Declines in developing countries were significantly sharper, with FDI returns falling to 7.8% by 2018 from 11.5% in 2011, while in Africa they almost halved over the same period, from 12% to 6.5%, UNCTAD figures show.

At the same time however, private-sector firms are under growing pressure from both civil society and their own investors to contribute more to sustainable development and improve their ESG credentials. This may offer window of opportunity for LDCs to compete for a bigger share of higher-quality, more sustainable FDI – but only if they can help firms be adequately rewarded with better commercial returns.

Treat FDI better

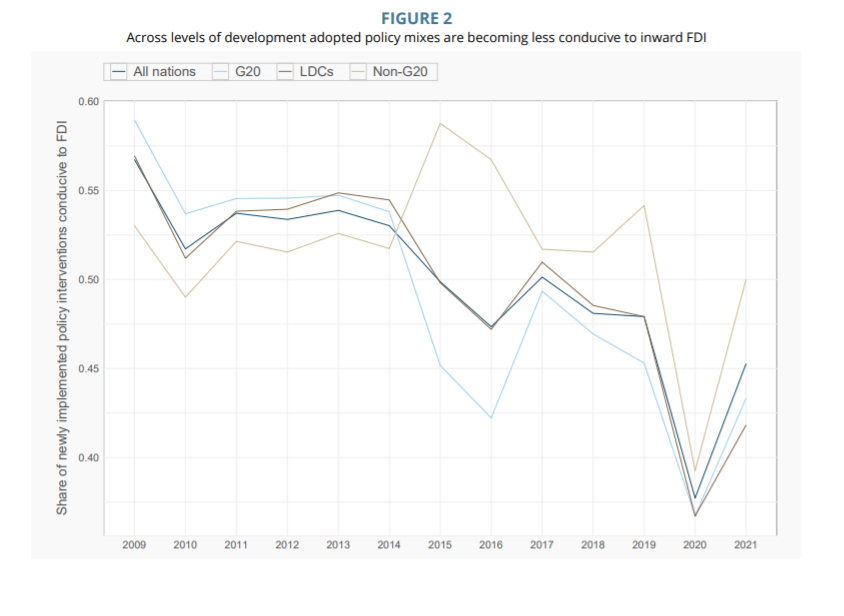

Treatment of FDI has also deteriorated across the board since 2014, with FDI-conducive policies at both G20 countries and LDCs falling sharply between 2019 and 2020 to less than 40% of all newly implemented policies, the Global Trade Alert Report found.

Figure 2 Global Trade Report June 2 2021, p27

Cambodia however offers one positive example of how policies aimed at supporting FDI inflows and financial returns can reap rewards, according to Evenett.

Although Cambodia was not immune to Covid-19 – with Coface figures pointing to a 49% year-on-year decline in foreign investment in the first quarter of 2020 – its FDI inflows had reached a record high the previous year, growing 16% to $3.7 billion, according to UNCTAD. And even in 2020, the Council for the Development of Cambodia (CDC) approved 238 investment projects worth $8.2 billion across a good mix of sectors.

Ways the kingdom has facilitated foreign investment include the creation of special economic zones (SEZs) that provide businesses with access to land, infrastructure and services, and the introduction of incentives such as corporate tax holidays, 100% ownership of companies and duty-free import of capital goods.

Self-reflect with development bank support

LDCs looking to reboot their FDI should start by examining their own track record, seeking to establish which policies or corporate practices are responsible for the rates of return multinational corporations’ foreign affiliates generate in their country, as well as what is driving up perceived risk levels and what impact FDI has on the ground, the report recommends. Partnering with the World Bank or a regional development bank should help this process.

Policy makers should then develop an FDI framework that not only helps their country compete against other locations for foreign investment but makes it more lucrative for companies to invest in the country than simply export to it, Evenett argues.

Target incentives at priority sectors

Policies should ensure state aid for FDI is targeted only at sectors that the LDC has identified as most likely to benefit sustainable development, the report advises. Enhanced incentives should also be offered for investments that facilitate the transfer of innovations that deliver progress towards priority sectors.

A list of these sectors should be made public to inward investors and potential donor governments, it adds.

Resist erecting trade barriers

The erection of trade barriers has long been recognized as a potential tactic for countries looking to attract more FDI from foreign companies that want to reach new markets.

“Governments can try and secure more FDI by blocking out exports and making firms jump the trade barrier and invest in the country,” Evenett noted. However, “our experience of that is it’s a disaster.”

One unintended consequence of introducing tariff or non-tariff barriers is that LDCs’ low-income populations end up paying more for essential goods and services, such as food, medicines or education, he explains. It is far better in such cases therefore to properly incentivize investment in local production capacity from the outset, he argues.

Ensure transparency and stability

Whatever improvements LDCs make now, policy stability and transparency will be key to de-risking FDI in the future, Evenett adds. Any FDI framework should therefore have a five- to 10-year shelf life and be made clear and accessible.

To make long-term investments, companies need to be able to research and understand regulations easily and have confidence they won’t change halfway through a project. “Uncertainty is the killer of investment,” he concludes.

To read the full commentary by Enhanced Integrated Framework, please click here.