Before Donald Trump became president in 2017, Americans paid tariffs on just two percent of their imported goods. The average tariff rate was 1.7 percent.

In 2018, however, Trump launched his global trade wars. “[W]e have a Trade Deficit of $500 billion per year,” he tweeted in April 2018. “We cannot let this continue!” He slapped tariffs on two-thirds of Chinese exports and on metals sold by nearly every other country—friend and foe alike. By the end of that year, Americans were paying tariffs on 15 percent of their imports. By 2019, the average tariff rate had shot up to 13.8 percent.

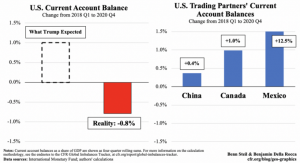

As the left-hand figure above illustrates, Trump expected his massive wall of tariffs to push the U.S. current account balance (of which trade is the biggest component) upwards, toward surplus. Yet the reality, as we now know, is that it fell deeper into deficit.

And what happened to the countries which were the primary target of Trump’s ire? As the right-hand figure shows, the current account balances of China and NAFTA partners Canada and Mexico all increased. Mexico’s balance rose by a whopping 12.5 percent. And recall that Trump had claimed that Mexico had “paid for the wall” through the change in trade flows wrought by his USMCA agreement. Nothing could be more logically or empirically preposterous.

So how did Trump get tariffs so wrong? Well, first, the countries he targeted retaliated. Canada and Mexico slapped tariffs on American metals. And China imposed tariffs on a whopping 58 percent of U.S. exports. Second, the tariffs hurt the export competitiveness of U.S. companies which had to pay more for critical intermediate goods imported for use in domestic production. Third, and most importantly, tariffs, in theory as well as practice, have little influence on trade balances. Instead, macroeconomic factors—such as fiscal policy, demographics, domestic demand, exchange rates, and supply-side policies such as state subsidies—have predominant influence.

Most damning, however, is the fact that the trade balance, as we’ve pointed out before, bears no empirical relation to either GDP growth or employment. This fact means not just that the effort to move it through tariffs is bound to failure, but that any movement toward surplus will not, in itself, improve a country’s economic welfare. Trump therefore committed the double sin of doing the wrong thing for the wrong purpose—and harming American industry, workers, and consumers in the process.

To view the original blog post, please click here