One of the instruments many governments resorted to in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic was trade policy. Barriers to the importation of medical products and supplies and agricultural and food products were lowered, and restrictions imposed on exports of such goods. The mix of import facilitation and export controls was driven by the objective of maximising the availability of critical supplies in the domestic market.

Early in the pandemic, many analysts and organisations stressed the importance of keeping borders open to allow international production networks to work efficiently in ramping up supply of critical products (e.g. Bown 2020a, 2020b, Espitia et al. 2020, Mattoo and Ruta 2020, Mirodout 2020, OECD 2020, WTO 2020). Real-time tracking of the use of trade policy measures affecting supply chains is difficult as governments only report changes in trade policy to the WTO with a lag and may not notify the WTO at all. Timely information on trade policy measures matters for businesses seeking to expand production and needing to source inputs to do so, to public authorities responsible for procuring critical supplies, and for policy analysts interested in assessing the effects and effectiveness of policy responses to the pandemic.

This column introduces a new dataset on trade policy interventions – both to control exports and facilitate imports of food, medical supplies, and personal protective equipment (PPE). The dataset is the product of an ongoing open data initiative conducted by the Global Trade Alert (GTA) in partnership with the European University Institute and the World Bank to collect information on changes in trade policy towards exports and imports of medical and food products starting in January 2020.1

The database

The data-collection initiative presented was confined to trade policy changes in two sectors: medical goods and medicines, and agricultural and food products. The products falling under each of these sectoral headings are listed in the methodology note that accompanies the database (GTA 2020). Policy interventions by national and sub-national governments, as well as actions taken at the supra-national level by a customs union are included in the data collection exercise.

Trade policy measures are identified using the following methodology. First, automated techniques are used to gather information in multiple languages on relevant trade policy changes from many different sources including websites of relevant government agencies, international organisations, online media sources including social media, and non-state organisations collecting information on the matters falling within the scope of this exercise, such as law firms and research institutes.

These sources are searched for key words in major languages relating to the policies and products falling into the two sectors of interest. Such searches create ‘leads’ which are processed to identify those that legitimately characterise a trade policy change falling within the scope of the initiative. Every lead recorded in the GTA’s systems is enriched in a multi-step analytical process aimed at assessing the relevance and validity of the policy.

The resulting database on trade policy changes includes information on the sector affected (medical products and/or food); the type of information used to document the trade policy change (official source, report on the Global Trade Alert website, media sources, other reports); the jurisdiction implementing the trade policy change; an initial assessment of whether the trade policy change is liberalising or restrictive; where relevant/available, the date the trade policy change was announced/was implemented and lapsed; and whether the trade policy change affects imports and/or exports.

The version of the dataset used in our accompanying paper spans the period up to 9 October 2020 (Evenett et al. 2020). It includes 701 policy measures covering 135 customs territories. For the ensuing descriptive analysis of trade policy measures across countries and over time, we consider the date of announcement as the starting date of each measure. After cleaning the data to remove inconsistencies in reported measures and excluding measures announced before the COVID-19 outbreak, we are left with 645 measures, of which 284 have no removal date indicated and 52 are to be removed in 2021 or later.

Stylised facts

The data reveal several stylised facts on trade policy changes over the first nine months of the COVID-19 pandemic:

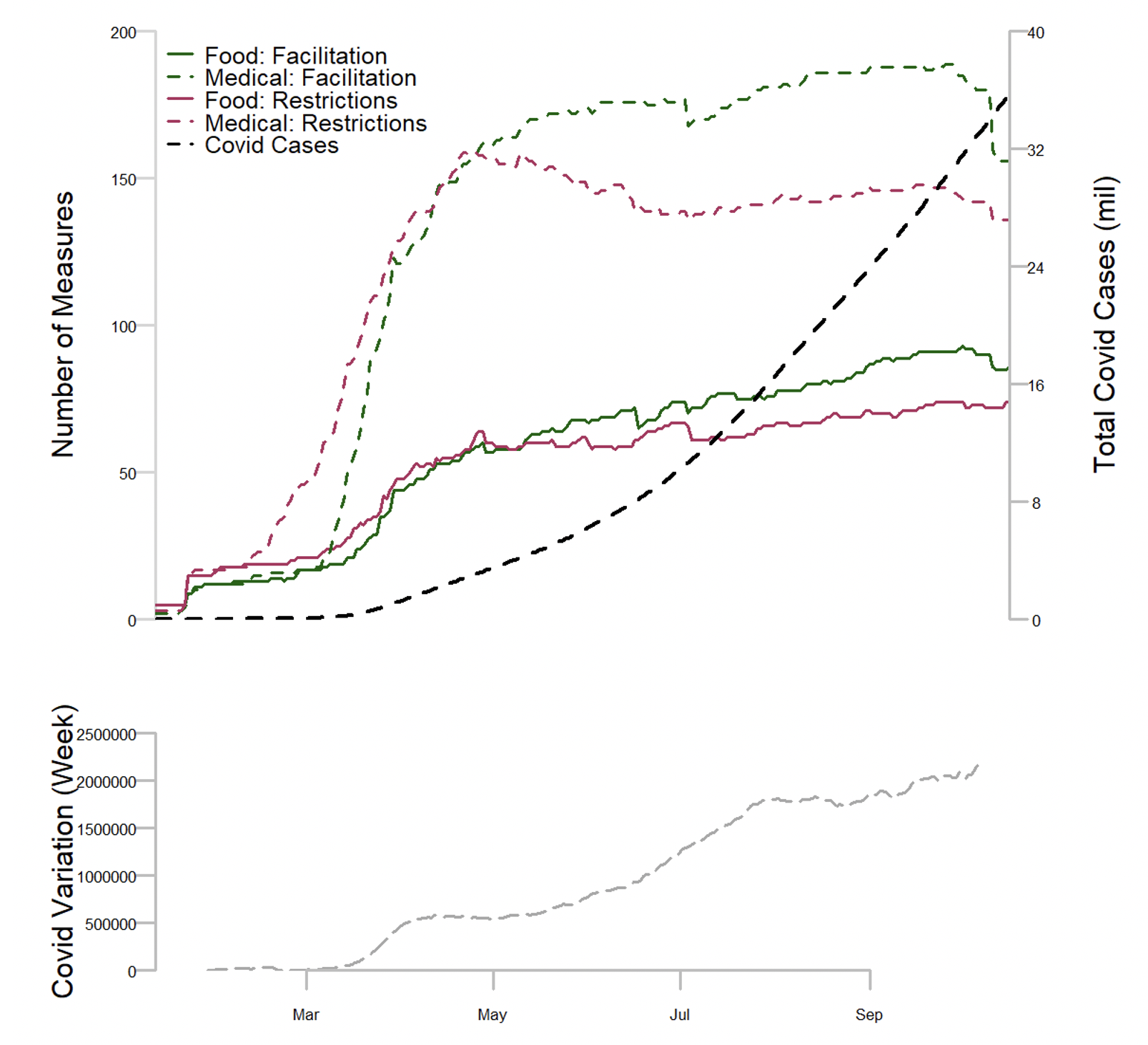

- There was a big jump in trade policy activism starting in February 2020. This accelerated in March, with the initial increase occurring in tandem with the rise in the number of COVID-19 cases (Figure 1). At the global level, there is an approximate balance between temporary and open-ended measures, but there is significant heterogeneity at the regional/country level.

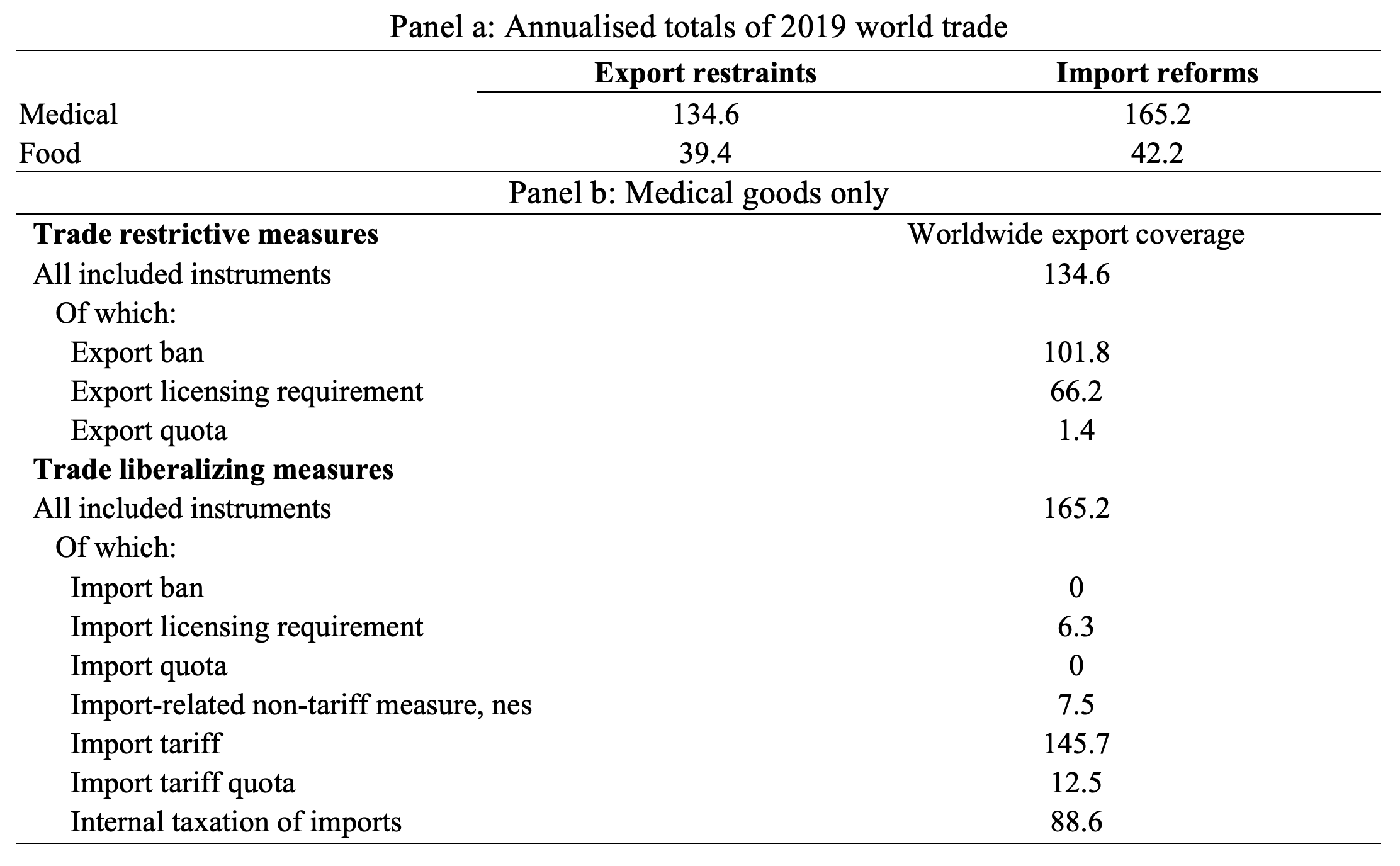

- Measures targeting medical products and PPE dominate, accounting for two-thirds of all trade measures taken. Food is less in focus. In terms of the value of 2019 trade covered, trade policy changes in medical goods outweigh those in food products by a factor of three or more.

- Export curbs in medical goods covered international trade worth $135 billion (of 2019 trade), whereas import reforms in the same sector covered $165 billion. In the case of food and agri-food products, the comparable totals are $39 billion and $42 billion, respectively (see Table 1). Because these estimates are based on 2019 (i.e. pre-pandemic) trade data, they may understate the magnitudes of implicated trade, especially for medical products.

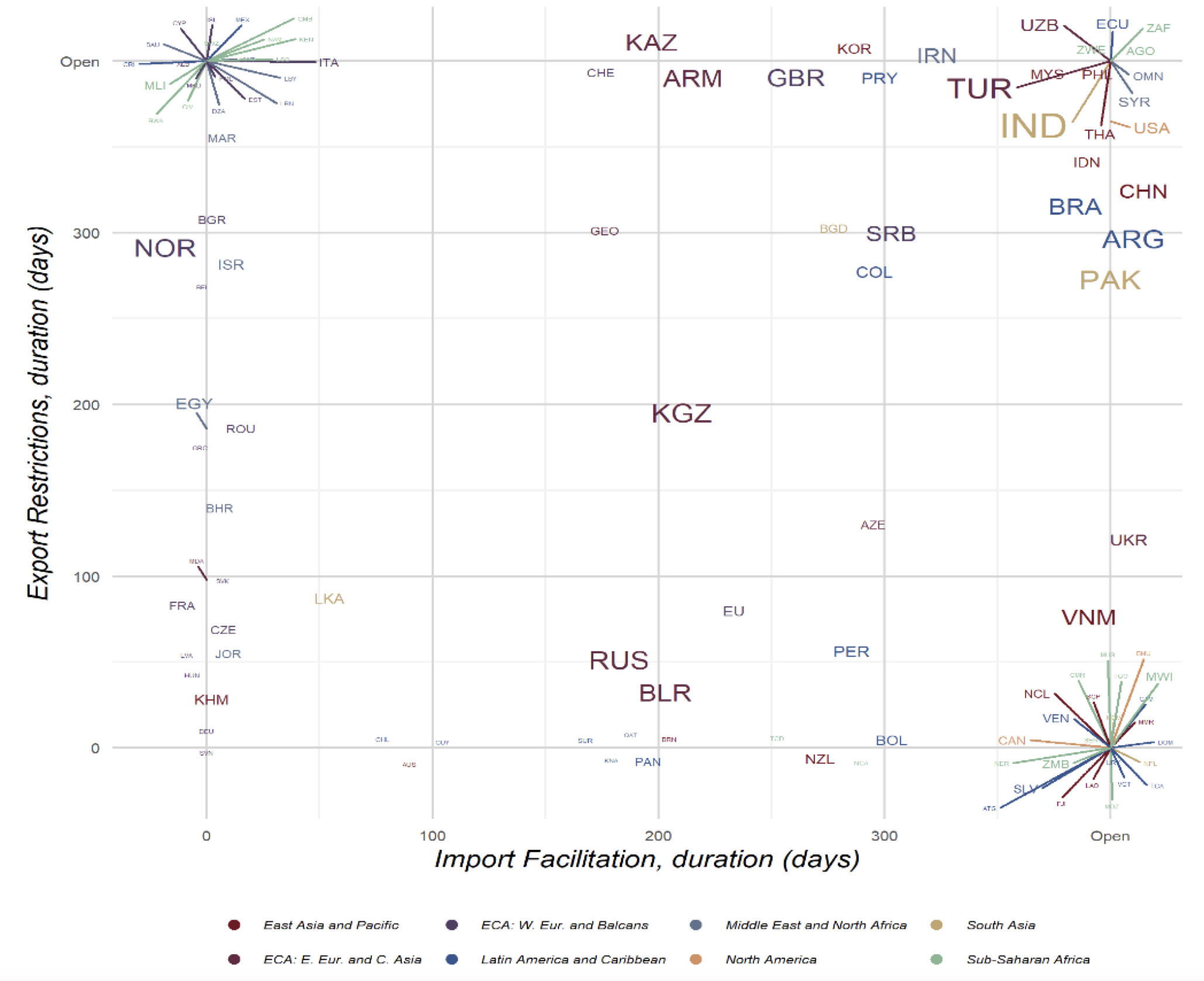

- Countries responded to the COVID-19 pandemic with different combinations of export controls and import liberalisation measures. Some countries acted both on the restrictive and liberalising side, creating long-term changes in their pre-COVID trade policy structures for the food and medical sectors; other countries acted only on one side, either restricting trade or liberalising it (see Figure 2 for medical products). Although many countries resorted to trade policy instruments, it is noteworthy that many did not resort to trade policy tools at all.

- There is also substantial heterogeneity across countries in the types of trade instruments used and the extent and speed with which crisis-motivated trade measures were removed.

Figure 1 Global COVID-19 cases and trade policy measures

Notes: For each regional sub-figure the upper part plots the number of active trade policy measures and the absolute number of COVID-19 cases over time while the lower part plots the weekly variation of COVID-19 cases.

Source: COVID-19 data from John Hopkins University CSSE database.

Table 1 Trade coverage of measures tracked by the GTA database (US$ bn)

Figure 2 Trade policy responses: Who did what for how long?

Notes: Coloured lines point to the names of countries located in the same space of a graph. Countries are displayed in terms of the duration (in days) of the longest period with at least one active import liberalization measure (horizontal axis) and at least one active export restriction (vertical axis). The value “Open” at the end of each axis identifies measures without an end date or that extend beyond December 2020. The font size of each country code is proportional to the total number of measures implemented; colours identify the associated world region.

Research questions raised

The patterns of observed trade policy activism in response to the COVID-19 pandemic raise many questions regarding the determinants and underlying political economy of trade policy. In the paper accompanying the dataset, we have suggested several areas for research using the dataset and hope the data collection exercise will stimulate such research (Evenett et al. 2020).

Understanding the motives underlying choices in the design and implementation of trade policy responses to the pandemic, reflected in the substantial cross-country heterogeneity observed in the data, is one line of fruitful research.

Another concerns quantification of the effects of different trade policy strategies, both for the world as a whole and for the countries concerned. The preliminary analysis reported in our paper suggests that export bans increased international prices of critical medical goods, especially for PPE.

A third policy research question the data can help address revolves around the broader question of the value of trade agreements. To what extent did countries comply with basic provisions of trade agreements calling for transparency, and for trade restrictions in response to emergencies to be temporary and necessary? These are just some of the research questions suggested by the stylized facts revealed by this dataset. No doubt there are many others.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this column are those of the authors and they do not necessarily represent the views of the World Bank Group.

References

Bown, C (2020a), “Trump’s trade policy is hampering the US fight against COVID-19”, PIIE blog, 13 March.

Bown, C (2020b), “EU limits on medical gear exports put poor countries and Europeans at risk”, PIIE blog, 24 March.

Espitia, A, N Rocha and M Ruta (2020), “COVID-19 and Food Protectionism: The Impact of the Pandemic and Export Restrictions on World Food Markets”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 9253.

Evenett, S J, M Fiorini, J Fritz, B M Hoekman, P Lukaszuk, N Rocha, M Ruta, F Santi and A Shingal (2020), “Trade Policy Responses to the COVID-19 pandemic crisis: Evidence from a New Dataset”, EUI Working Paper RSCAS 2020/78.

GTA (2020), “The COVID-19 Pandemic: 21st century approaches to tracking trade policy responses in real-time”, Methodological Note, 4 May.

Mattoo, A and M Ruta (2020), “Don’t close borders against coronavirus”, Financial Times, 13 March.

Miroudot, S (2020), “Resilience versus robustness in global value chains: Some policy implications”, in R E Baldwin and S J Evenett (eds), COVID-19 and Trade Policy: Why Turning Inward Won’t Work: 117-130. London: CEPR Press.

OECD (2020), “COVID-19 and International Trade: Issues and Action”.

WTO (2020), “Trade in Medical Goods in the Context of Tackling COVID-19”, 20 April.

Endnotes

1 Information on trade policy changes are processed and collated by the Global Trade Alert team. The data are posted at https://www.globaltradealert.org/reports/54; https://globalgovernanceprogramme.eui.eu/covid-19-trade-policy-database-food-and-medical-products/ andhttps://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/trade/brief/coronavirus-covid-19-trade-policy-database-food-and-medical-products.

To view the original post, please click here