SUMMARY

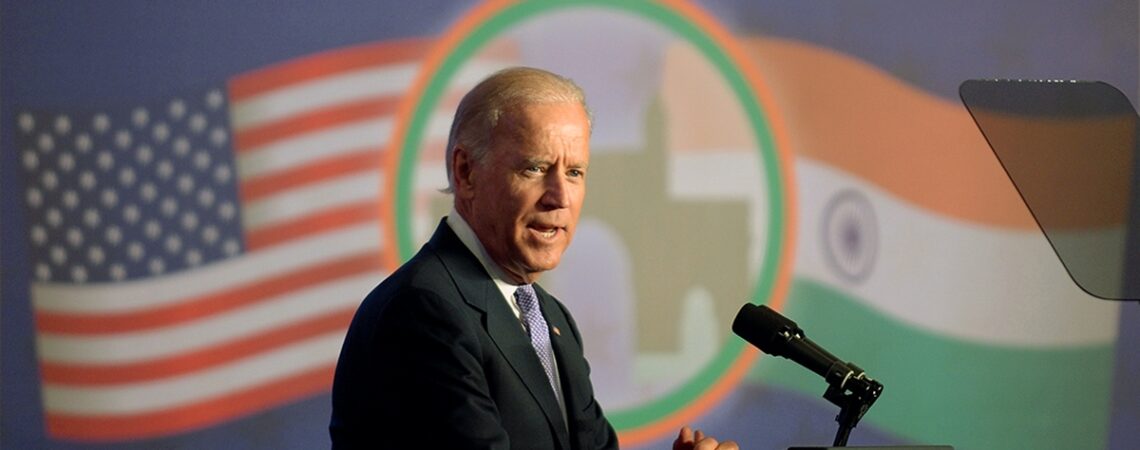

The state of the U.S.-India relationship is strong, but two critical developments in 2020 have created a new inflection point for the relationship. Growing apprehension in both New Delhi and Washington about Chinese aggression has created the strategic convergence long sought by a U.S. defense establishment eager to enlist India to balance China. On the other hand, devastated by the Covid-19 global pandemic, the United States and India face challenging economic recoveries amid growing protectionist sentiments at home that could diminish the relationship’s promise. Having won the U.S. presidential election, Joe Biden has an opportunity to consolidate and accelerate the relationship by creating a substantive and broad partnership with India, which can undergird U.S. policy in Asia and support U.S. global interests for decades to come. This paper provides a blueprint for how the Biden administration can actualize what previous presidents have deemed a “natural partnership.”

AMID DISCORD, SEEDS OF A NATURAL PARTNERSHIP

Speaking at the Asia Society’s headquarters in New York in September 1998, Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee deemed the United States and India “natural allies.” Both his message and timing were provocative. India’s leader was framing the relationship in lustrous terms at a time when bilateral ties had hit rock bottom. Months earlier, India had scandalized the world by conducting its first nuclear tests since 1974. The international community swiftly denounced the tests, and the United States, which had not been given advance warning by the Vajpayee government, imposed heavy sanctions on India.

While an official alliance had always been out of the question, nuclear policy had become an impediment even to a natural partnership. The previous months had been characterized by acrimony because of India’s nuclear decision and U.S. fears that India’s actions would spark a dangerous nuclear arms race in South Asia – this was borne out within 15 days of India’s tests when Pakistan conducted tests of its own. The two South Asian rivals fought each other the next year in the Kargil War, forcing the United States into intensive shuttle diplomacy to prevent a full-scale conflict.

Strange as they may have seemed at the time, Vajpayee’s words would prove prescient. The prime minister was cognizant of the structural and institutional forces that made a convergence between the United States and India inevitable. One was strategic (China’s rise), the other economic (India’s growth story), and at the base was a foundation of shared democratic values.

A new generation of U.S. policymakers was also receptive to these possibilities. In March 2000, Bill Clinton became the first U.S. president to visit India since Jimmy Carter in 1978. His visit led to the kind of reset in the bilateral relationship that Vajpayee had sought. Twenty years later, the U.S.- India relationship is stronger than it has ever been. Bilateral trade in goods and services has increased from $16 billion in 1999 to $149 billion in 2019 when India was the ninth-largest U.S. trading partner, while India’s Ministry of Commerce deemed the United States its largest trading partner. Cultural and people-to-people ties between the two nations, driven by the vibrant Indian American community in the United States, are multifaceted and deep. For instance, the number of Indian students in the United States has grown from 81,000 in 2008 to “a record high of 202,000 in 2019.” And in an otherwise polarized country, both major U.S. political parties support strengthening ties with India.

Now as the United States is set to embark on the administration of Joseph R. Biden Jr., the relationship is facing new tests. Biden, who deemed India a “natural partner” on the campaign trail, will have the task of upgrading a mature relationship already in robust shape at a time of new global dynamics and challenges. A growing convergence between the views of New Delhi and Washington regarding Beijing will continue to facilitate a strong security partnership. At the same time, the coronavirus pandemic has devastated both economies and strengthened support for economic nationalism, which may impede

stronger commercial cooperation and the two nations’ ability to take on China. Moreover, a further weakening of democratic norms in India could raise difficult questions for the United States.

This paper seeks to outline the competing pressures currently shaping U.S.-India ties and provides a blueprint for how the next U.S. administration can substantially advance the partnership, nurturing what Vajpayee, more than 20 years ago, and Biden today consider “natural.” To advance U.S.-India ties to the next level, a Biden administration will need to

• Expand the scope of the relationship to elevate health, digital, and climate cooperation.

• Turn the page to a positive commercial agenda that emphasizes reform and openness.

• Renew U.S. leadership and regional consultation in the face of China’s rise.

• Emphasize shared values as the foundation of the relationship.

Anubhav Gupta is an associate director with the Asia Society Policy Institute (ASPI) in New York. He develops and coordinates ASPI’s initiatives and research related to South Asia, with a particular focus on India.

To view the full paper, please click here

Nature and Nurture_How the Biden Administration Can Advance Ties with India