Congress passed the U.S. Foreign-Trade Zone Act (P.L. 73- 397, 19 U.S.C. §§ 81[a-u]) in 1934, which authorized the creation of the FTZ Program. The intent of the program was to encourage international trade and increase U.S. exports. FTZs are designated areas of the United States into which zone users may import goods duty-free, subject to certain requirements, for warehousing or production purposes within the zones. Duties are collected when goods leave the zones for consumption in the United States and not when exported. Similar programs exist in many other countries. The FTZ Act assigns administrative duties to the FTZ Board, which establishes, operates, and maintains FTZs. The FTZ Board is chaired by the Secretary of Commerce, The Secretary of the Treasury serves as the Board’s executive officer. The Secretary of Commerce appoints the Executive Secretary, who is supported by a staff of eight. The Department of Homeland Security’s Customs and Border Protection (CBP) advises the Board and enforces regulations, including protection and collection of tariff revenue.

Every CBP port of entry is allowed to have at least one zone. FTZs are required to be within 60 miles or 90 minutes driving time from the outer limits of a port of entry so CBP can conduct compliance reviews. Zone operators (grantees) are usually state or local governments, port authorities, and economic development organizations. Grantees are required to operate zones as a public utility and provide equal treatment to all zone users.

Zone Types

Until 2008, the FTZ Program designated specific areas to operate as general purpose zones that host multiple users under the Traditional Site Framework (TSF). The FTZ Board cited the TSF as an outdated model that “imposed a major burden on applicants, took a long time, and consumed too many government resources.” To provide flexibility to the FTZ program and expedited procedures, the Board adopted the Alternative Site Framework (ASF) in December 2008. The ASF operates as a service area within 60 miles or 90 minutes driving distance of a CBP port of entry and introduces two types of sites: (1) magnet sites meant to attract multiple users to a single area like a general purpose zone, and (2) usage-driven sites that would bring zone designation to a single user (subzones). Users looking for FTZ designation within a service area can obtain it for eligible facilities within 30 days. Subzones can also be established outside an ASF service area as long as CBP determines the ability to oversee it, but approval will require a longer process of up to five months. Zones under the TSF have an option to reorganize under the ASF. Today, around two-thirds of approved zones and most new zone applications fall under the ASF.

FTZ Activity Snapshot

According to the FTZ Board’s 2017 annual report, there were 191 active zones (out of the approved 262) and each state (plus Puerto Rico) has at least one zone. Over 450,000 people were employed at roughly 3,200 firms that used FTZs during the year. The total value of merchandise received in FTZs was $670 billion. This includes domestic goods brought into the zones from elsewhere in the United States, foreign goods imported into the zones for which duties have already been paid (also considered to have domestic status), and imports on which duties have not yet been paid (considered to have foreign status). Domestic status goods represent the majority of merchandise entering FTZs. In 2017, 63% ($419 billion) of goods were domestic status compared to 58% ($429 billion) in 2012.

Once in a zone, goods may be stored, assembled, destroyed, or manufactured. The majority of goods in FTZs is used in production activities. Production activity is defined as activity that causes substantial changes of a foreign article or the change in customs classification for the article. In 2017, there were 329 active production operations and 61% of imported goods were used in production activity. Foreign goods imported into FTZs duty-free in 2017 accounted for 10.6% of total U.S. goods imports. Major product categories were oil/petroleum and consumer electronics, which respectively made up 28% and 22% of foreign status goods (Figure 1). Exports from FTZs accounted for approximately 6% of U.S. goods exports.

Potential Benefits and Concerns

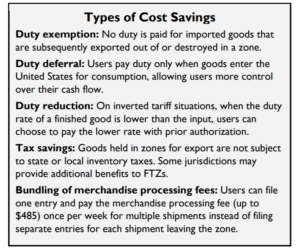

The FTZ Program offers zone users a variety of cost savings including duty exemption, duty deferral, duty reduction, tax savings, and bundling of merchandise processing fees (see text box on “Types of Cost Savings”). They may also benefit from improved logistic efficiencies, such as direct delivery of merchandise into FTZs and ease of transfers between zones. In general, users that benefit the most from FTZs are those that deal with high volume activity.

Supporters of FTZs argue that the program has an overall positive impact on the U.S. economy as it provides incentives for companies to keep manufacturing operations in the United States due to its tariff benefits. This, they argue, generates manufacturing jobs as well as service jobs in the communities surrounding FTZs. A 2017 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report, however, found that few studies had been done on the economic impact of FTZs, and noted that these studies are mostly theoretical and lack quantitative analysis. GAO also raised concerns on CBP’s ability to assess and respond to compliance risks across the program. In response, CBP has since conducted a program-wide risk assessment in 2018 and continues to update its compliance review handbook.

Some companies have raised concerns that tariff exemption and reduction put competing domestic producers at a disadvantage when zone users opt to import rather than source domestically. There are also concerns that those benefits result in a loss of tariff revenue for the United States, although U.S. tariffs constitute a small part of total government revenue. Furthermore, some opponents of FTZs argue that few industries benefit from the program and the resources required to operate in a zone, including the application process, make the program less accessible to all companies. The FTZ Board attempts to address these concerns by inviting input during the application process from domestic stakeholders that may face a negative impact from new FTZ activity, as well as streamlining the application process to increase accessibility to the program.

Application Process

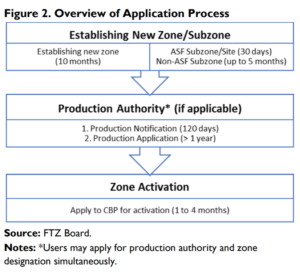

The application process may require additional administrative costs that affect accessibility. Operations may commence as soon as CBP activates the zone, unless users intend to use it for production activity. In that case, users are required to apply for production authority from the FTZ Board (Figure 2). This additional step, which includes a public comment period, seeks to ensure domestic suppliers are not harmed as a result of foreign import competition. In 2012, the FTZ Board implemented new regulations that simplified the production application process, and introduced an optional two-stage procedure, potentially shortening the processing time from more than one year to 120 days.

In the first stage, grantees, on behalf of the user, submit a production notification. If the FTZ Board does not find issues during the 120-day review and stakeholders do not object during the public comment period, the user can begin production activity with full approval or partial approval for specified goods. If full approval is not given, companies have the option to submit a production application for consideration under a more extensive review process based on a set of criteria listed under FTZ regulations (15 C.F.R. §400.27). In response to concerns raised by GAO, the FTZ Board updated its procedures in November 2018 to document consideration of all criteria listed in the regulations during the review process.

Issues for Congress

FTZ users have access to tariff-related and logistical benefits, which may have become increasingly relevant in light of the Administration’s various tariff increases since 2018. Congress may conduct oversight of the program in general and explore specific issues, including:

- The costs required to gain access to and maintain operations in FTZs that may affect accessibility.

- The limited information on the program’s overall economic impact.

- CBP’s current efforts to update its compliance review handbook.

To access original source, click here