Following the annexation of the Crimean peninsula by the Russian Federation in 2014, the US, the EU, and some other countries imposed several sanctioning measures against Russia. These included restrictions on specific firms and individuals with close ties to the Russian government, as well as sector-wide measures that curtailed trade in goods related to the defense and energy sectors. In response, Russia imposed counter-sanctions on imports of foodstuffs from the US, EU, and other countries that joined the original sanctioning measures against Russia (van Bergeijk 2014).

This episode of mirrored sanctions packages is remarkable in at least two respects. First, these sanctions were imposed out of geo-political motivations, not because of economic considerations. If the sanctions had been imposed because of allegations of currency manipulations, or due to other economic factors, it would be exceedingly difficult to determine suitable counterfactuals for computing the effect of sanctions on trade flows. However, this episode is as close to a natural experiment as one can possibly get in the realm of international trade. The other remarkable factor is that these two distinct sanctioning measures happened in quick succession (between March and August 2014), prompted by the same original impulse, and involving the same set of countries. These similarities make it possible to attribute changes in trade flows to sanctions (Belin and Hanousek 2019), as all other factors are held constant naturally.

Impact of the sanctions

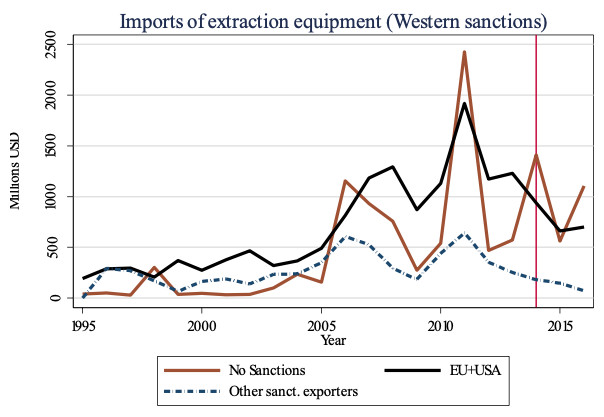

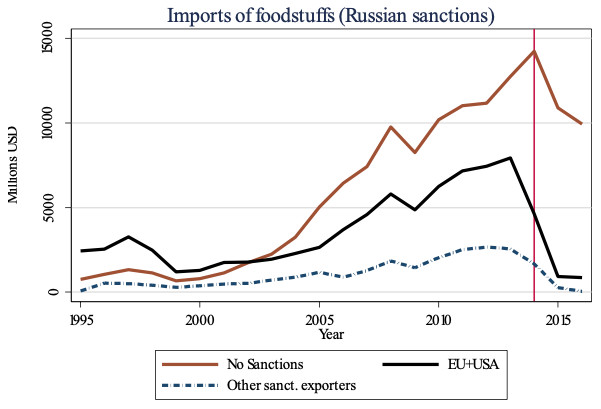

As a first step, we take the lists of goods sanctioned by the Western coalition and Russia and look at the aggregate inflows of these goods into the Russian Federation. Figures 1 and 2 show these aggregate inflows with the first year of sanctions, 2014, marked by a vertical red line.

Figure 1

Figure 2

As is apparent from both figures, trade inflows of the sanctioned goods declined significantly after 2014. A slight exception can be seen in the inflows of extraction equipment (for oil and natural gas) from non-sanctioning importers. However, this time series is very volatile, and was so even before sanctions, so no firm conclusions can be drawn from this. A certain degree of volatility in these imports is to be expected since mining equipment is imported in large, one-off deliveries when production capacities are being expanded (Crozet and Hinz 2016).

Since imports into Russia declined even from exporters who were not subject to sanctions, it is unlikely that the sanctions were responsible for the downward trend of imports after 2014. This is essentially the same conclusion drawn by Dreger et al. (2016), who find that the decline in oil prices was likely responsible for the weakening of the Russian rouble, which in turn could be responsible for declining imports, and for those imports becoming more expensive for Russian importers.

Perhaps even more importantly, the decline in inflows of goods from non-sanctioning exporters shows that, at least in the aggregate, there is no substitution of trade channels. Ex ante, it would not be unreasonable to expect Russian importers to switch away from suppliers in the sanctioning countries to others that are not subject to sanctions. Indeed, there are some anecdotal reports of individual cases of this behaviour (Yeliseyeu 2017), but the ‘big picture’ conclusion is inescapable – Russian imports have declined across the board, from sanctioning and non-sanctioning exporters alike.

The last feature of the figures that needs a more detailed explanation is the persistence of imports of extraction equipment from sanctioning exporters after 2014. In part, this is due to limitations of our dataset, which resolves product categories only at the 6-digit HS level, while the Western sanctions were imposed at the 8-digit level. This means that we are classifying very similar goods as sanctioned, while in reality the sanctions do not apply to them. In addition, the Western sanctions allow the exporters to honour the contracts made prior to the imposition of export restrictions. Hence, if the Russian importers have made sufficiently long-term contracts for the supply of extraction equipment, sanctioned goods can be imported into Russia legally.

In order to calculate the value of lost trade more precisely (as opposed to gauging it from the aggregate graphs above), we set up a differences-in-differences model of imports into Russia. To this end, we select product groups that contain the sanctioned goods as well as other similar items that are not subject to sanctions. The inflows of non-sanctioned goods serve as the counterfactual in this case, suggesting what would happen to the inflows of sanctioned goods in the absence of sanctions. Our approach utilises the natural experiment that occurred in this episode – we compare similar goods (with the same first four digits of their Harmonised System codes), some of which were essentially randomised into the sanctions ‘treatment’, while others were not, thus serving as ‘controls’.

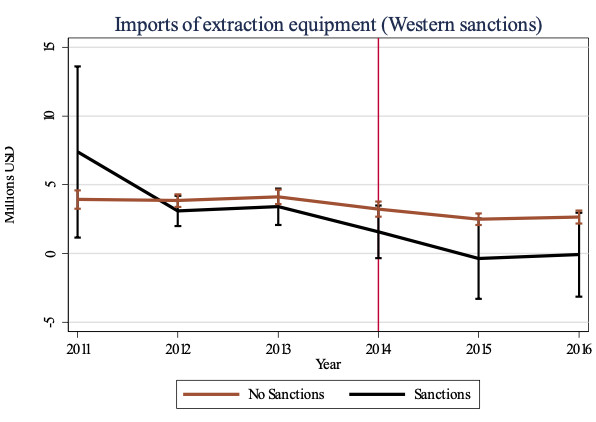

Figure 3

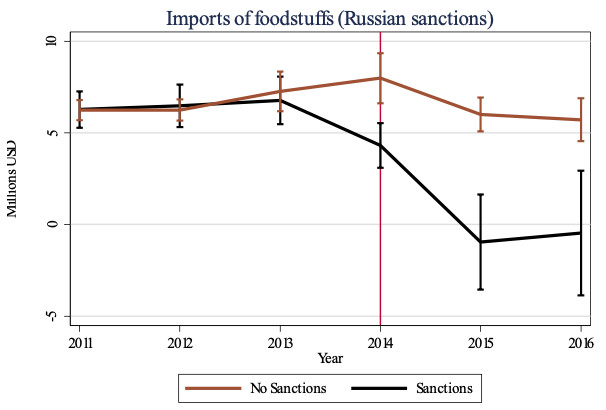

Figure 4

The differences-in-differences estimates are plotted above and show that while the Western sanctions may have had a modest downward effect on the imports of extraction equipment, the difference compared to the benchmark is slight and statistically insignificant. Overall, the lost trade amounts to about $1.3 billion (the 95% confidence interval goes from -$2.6 billion to +$0.02 billion). On the other hand, Russian counter-sanctions resulted in a much more pronounced decline in the imports of Western foodstuffs. Specifically, imports from sanctioned exporters declined faster than those from non-sanctioning ones. As a result, Russian counter-sanctions resulted in about $10.5 billion of lost trade (95% CI from -$15.6 billion to -$5.5 billion).

Conclusions

We interpret the differential impact of the Western and Russian sanctioning measures as consequences of the different ways these sanctions were imposed. While the EU and US sanctions targeted the exports of a very narrow class of goods with close substitutes, the Russian sanctions restricted trade imports in much broader terms. This policy difference may have enabled Russian importers to find close substitutes for the sanctioned products, and therefore the impact on goods that have been sanctioned at the 8-digit HS level is undetectable in data at the 6-digit level. It is also possible that in tandem with this substitution plan, Western exporters may be reclassifying their products, thereby sending the same exports as before under labels that do not fall within the sanctions regime. In addition, the Western sanctions allow for ‘grandfathered import’, in other words, exporters can be legally permitted to export sanctioned goods into Russia provided that the exports are made pursuant to a contract made prior to the imposition of sanctions. These features of the sanctions package make it easier to export Western extraction equipment into Russia than to export Western foodstuffs.

While there is evidence that the targeted Western sanctions have had a significant impact on the Russian firms and individuals on whom these sanctions were imposed (Ahn and Ludema 2016), we cannot confirm similar findings from the international trade standpoint. This suggests that the strategy of the Western coalition was to limit potential ‘collateral damage’ by imposing rather limited sectoral sanctions and focusing on individually targeted sanctions instead. In contrast, Russian counter-sanctions were meant to affect the European agricultural sector, which is what is reflected in the trade data.

References

Ahn, D P and R Ludema (2016), “Measuring Smartness: Understanding the Economic Impact of Targeted Sanctions”, U.S. Department of State Office of the Chief Economist Working Paper 2017-01.

Belin, M and J Hanousek (2019), “Which Sanctions Matter? Analysis of the EU/Russian Sanctions of 2014“, CEPR Discussion Paper 13549.

Crozet, M and J Hinz (2016), “Collateral Damage: The impact of the Russia sanctions on sanctioning countries’ exports”, CEPII Working Paper 2016-16.

Dreger, C, K A Kholodilin, D Ulbricht and J Fidrmuc (2016), “Between the hammer and the anvil: The impact of economic sanctions and oil prices on Russia’s ruble”, Journal of Comparative Economics 44(2): 295-308.

van Bergeijk, P A G (2014), “Russia’s tit for tat“, VoxEU.org, 25 April.

Yeliseyeu, A (2017), “Belarusian shrimps anyone? How EU food products make their way to Russia through Belarus”, Think Visegrad – V4 Think Tank Platform

[To read the original column, click here.]

Copyright © 2019 VoxEU. All rights reserved.