International markets can provide exporting firms with more opportunities to generate and introduce innovations and capitalise on their investments relative to purely domestic firms. Using German data, this column demonstrates that exporting firms introduce innovations more frequently than domestic firms and have higher economic gains from their innovations. Trade restrictions such as tariffs can affect a firm’s economic activities in foreign markets and also their R&D and innovation activities.

R&D investment is an important source of firms’ growth and long-run economic success. The theoretical literature on trade and growth, developed by Helpman and Grossman (1990, 1995), has emphasised the role that international trade can play in the speed and direction of endogenous technological change. Firms that operate in international markets may have more exposure to new knowledge and face better demand opportunities to exploit their innovations, and hence have greater incentive to invest in costly innovation. Empirical studies have found that firms that are active in international markets have higher rates of R&D investment, innovation, and patenting (Bustos 2010, Lileeva and Trefler 2010, Aw et al. 2008, 2011). These differences, in turn, contribute to differences in firms’ productivity levels and their long-run economic performance (Peters et al. 2017 and Shu and Steinwender 2018). While the EU and their member states have put in place numerous public policy measures to directly foster firms’ R&D and innovation activities, policies that affect trade conditions in foreign markets and their role in affecting the payoff to innovation should not be neglected. To understand how public policy may affect firm investment incentives, in particular, for firms that sell in international markets, it is necessary to understand how these firms make their R&D investment decisions.

R&D and innovation activities for firms with export market exposure

Firm R&D and innovation decisions result from a comparison between the current cost and expected long-run benefit to the investment. These measures are likely to differ across firms that are exposed to international markets and those that are not for the reasons outlined by Grossman and Helpman (1990, 1995). The difference in the expected benefit of investing between a firm that engages in international markets and one that does not is a combination of how different investments improve the firm’s productivity and how this change in productivity translates into firm’s profit.

In a recent paper, we estimate a dynamic structural model of firm R&D investment choice using German firm-level data from five high-tech manufacturing industries (Peters et al. 2018). We quantify both the cost of innovation and the expected long-run benefit of investing in R&D. The benefits depend on the linkages from R&D investment to product and process innovation to long-run productivity and profit improvements. These linkages can differ for exporting and non-exporting firms. R&D can have a different impact on the innovation rates of the two groups of firms because of the global exposure to a broader range of ideas or an ability to specialise innovations for specific markets. The innovations in turn may generate different economic returns for the two types of firms because of the size of the markets and differences in demand conditions.

Empirical results

Our empirical findings show that exporting firms introduce innovations more frequently than purely domestic firms. Among domestic firms that do not conduct formal R&D, only 17.3% are able to introduce a new product or process innovation in the next year, while this number rises to 26.4% among the exporting firms. Across all industries, if firms invest in R&D, their innovation rates increase substantially – to 76.8% and 91.3% for domestic and exporting firms, respectively. This pattern is consistent with the fact that R&D generates new knowledge and exporting firms with their exposure to international markets are better able to adopt this knowledge and have more pathways to create innovations.

Exporting firms also have higher economic gains from innovations than purely domestic firms.

- One reason is that serving more markets allows exporting firms to market their innovations to more consumers and enjoy larger scale effects.

- Second, we find that innovation even yields larger economic gains for exporting firms in the domestic market than for domestic firms.

Having both product and process innovations improves the domestic sales of an exporting firm by 6.6% whereas the improvement for a pure domestic seller is much less, 2.3%. In addition, the innovations increase export market sales for the exporting firm by 9.4%. When product and process innovations are distinguished, domestic sales and profits are primarily impacted by process innovations for both types of firms, while export market sales and profits are impacted by new product innovations. The ability to introduce new products into foreign markets has a substantial impact on the productivity and long-run performance of exporting firms.

- Third, the productivity processes differ in their degree of persistence.

Domestic sales productivity depreciates, on average, at 21% per year, while export sales productivity depreciates at 14% per year. This difference in depreciation rates means that new innovations by exporting firms will have a longer-lasting impact on future firm profits.

Altogether, the larger market scope, larger economic gains, and more persistent gains from innovation contribute to a larger payoff to R&D investment for exporting firms. Among the pure domestic firms in our sample, the median increase in firm value as a result of the R&D investment varies from 1.0–2.4% across the five high-tech industries. Among the exporting firms, however, the median increase in firm value varies from 4.6–10.8% across the industries.

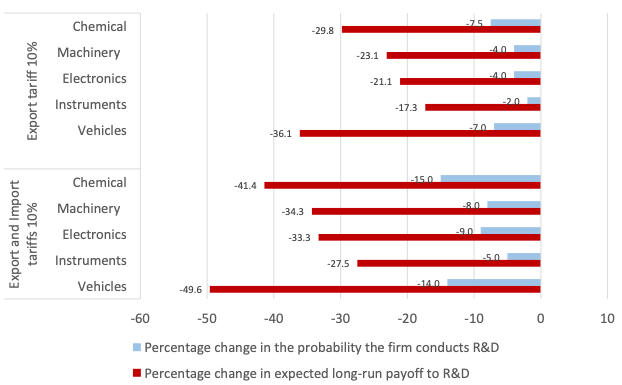

Given the substantial impact that foreign market sales have on the payoff to R&D, impediments to trade activities, such as export or import tariffs, can have a sizable impact on innovation activities for exporting firms. Simulations of our model show exactly this. If German firms faced a tariff of 10% in the foreign market, prices would rise and profits fall in that market. The lower profit translates into a reduction in the long-run benefit of R&D investment for these firms that ranges between 17.3% in medical instruments and optics and 36.1% in vehicles (Figure 1). As a result, the proportion of firms choosing to invest in R&D decreases between 2.0 and 7.5 percentage points.

Retaliation by Germany with a 10% import tariff on foreign products increases the production cost for their exporting firms and hence increases the price the firms charge in domestic and foreign markets. The combination of export and import tariffs results in exporting firms losing between 27.5% and 49.6% of the long-run payoff to R&D and substantially dampens R&D investment by 5.0–15.0% across the high-tech industries. Exporting firms in vehicles and chemicals would be most affected by such trade policy.

Figure 1 Impact of export and import tariffs on the probability of investing in R&D and long-run payoffs to R&D

Conclusion

Our research shows that differences in firm R&D investment between exporting and non-exporting firms can be explained by the differences in the long-run return to investment. Exporting firms have higher rates of product and process innovation, and these innovations yield higher economic return for exporting firms than non-exporting firms. This presumably reflects better access to ideas and the ability to market their innovation on a larger scale. For exporting firms, investment incentives however also depend on trade policies. Policy measures that affect firms’ profit in export markets substantially affect their investment decisions and hence their long-run firm values.

References

Aw, B Y, M J Roberts and D Y Xu (2008), “R&D investments, exporting, and the evolution of firm productivity,” American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings 98(2): 451–456.

Aw, B Y, M J Roberts and D Y Xu (2011), “R&D investment, exporting and productivity dynamics,” American Economic Review 101(4): 1312–1344.

Bustos, P (2010), “Multilateral trade liberalization, exports and technology upgrading: Evidence on the impact of MERCOSUR on Argentinean firms,” American Economic Review 101(1): 304–340.

Grossman, G M and E Helpman (1990), “Trade innovation, and growth,” American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings 80(2): 86–91.

Grossman, G M and E Helpman (1995), “Technology and trade,” in G Grossman and K Rogoff (eds), Handbook of International Economics, Vol III, Elsevier Science: 1279–1337.

Lileeva, A and D Trefler (2010), “Improved access to foreign markets raises plant-level productivity… for some plants,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 125(3): 1051–1099.

Peters, B, M J Roberts and V A Vuong (2018), “Firm R&D investment and export market exposure,” NBER, Working paper no 25228.

Peters, B, M J Roberts, V A Vuong and H Fryges (2017), “Estimating dynamic R&D choice: An analysis of costs and long-run benefits,” Rand Journal of Economics 48(2): 409–437.

Shu, P and C Steinwender (2018), “The impact of trade liberalization on firm productivity and innovation,” NBER, Working paper 24715.

[To read the original paper, click here.]

Copyright © 2019 VoxEU. All rights reserved.