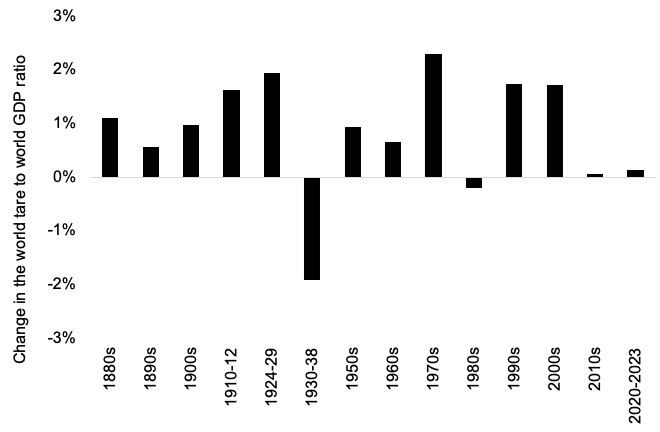

While economists agree that the multilateral trading system is under pressure and that US trade wars and the Brexit chaos provide examples of behaviour that is completely new for the present generation, it is still unclear if we are actually in the midst of deglobalisation (O’Rourke 2018, 2019). Deglobalisation would imply a fundamental change in our economic environment but not a new phenomenon from a long-run perspective, because a period of significant deglobalization also occurred in the 1930. We can glean from history the pattern of emerging deglobalisation (van Bergeijk 2019). Figure 1 illustrates this historical perspective of alternating waves of globalisation (a more open world economy) and deglobalisation by means of the change in the world trade to world output ratio.1 The figure shows that strong globalisation phases are followed by decades in which the world’s trade-to-GDP ratio decreases or stagnates. What does the current pattern of emerging deglobalisation look like?

Figure 1 Change in openness 1880-2023

(average annual change per decade of the world trade to world production ratio)

Notes: The estimate for 2010-2023 is (partly) based on IMF forecasts. Note that the number of available years is limited in the 1910s and 1930s and the absence of the 1940s.

Sources: Maddison (1995, 2001), World Bank World Development Indicators, and IMF World Economic Outlook data base.

Deglobalisation 2.0

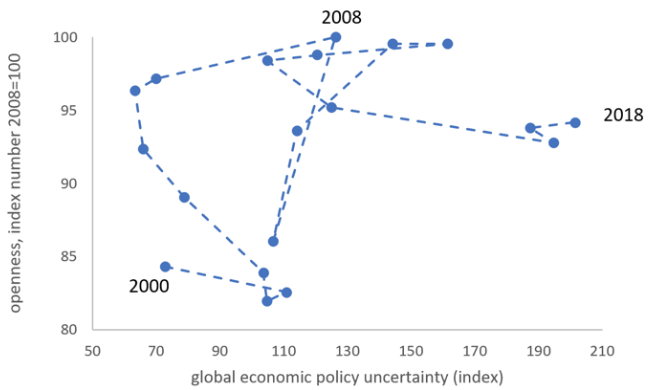

The start of the deglobalisation phase is a major economic crisis that reduces demand, increases uncertainty, and destroys confidence. Next follows a collapse of world trade and investment (Baldwin 2009). The collapse marks the end of decades of intensifying globalisation, and increasingly free international trade and capital flows. The start of a period of deglobalisation at first remains hidden under the veil of initial economic recovery, but later becomes clear and measurable. Figure 2 shows this pattern for the most recent phases and turning point. In the early 2000s openness (on the vertical axis) increased until it reached an all-time high in 2008 and from there deglobalisation sets in. Deglobalisation actually gains momentum around 2013 (and this leads to the recognition of the world trade slowdown; see Hoekman 2015). At the same time, uncertainty (on the horizontal axis) increases and moves into unknown territory. The figure makes an important point: deglobalisation started well before Trumpism and Brexit came on the horizon. Rather than being the causes of deglobalisation, we should therefore treat them as symptoms – the world had already started to change fundamentally and the wave of deglobalisation that we are currently experiencing may be here to stay for quite some while.

Figure 2 Openness and economic policy uncertainty of the world economy

Sources: Davis (2016) and data underlying Figure 1.

The major difference between the 1930s and the 2000s is that authoritarian countries in the era of the Great Depression where more likely to reduce trade and openness, whereas reductions of trade and openness during the Great Recession were more likely to occur in democracies (van Bergeijk 2018). To some it may be especially worrying that the clearest manifestations of deglobalisation occur in democracies, because democracies built the Bretton Woods institutions (and the EU). Indeed, the popular anti-globalist movements currently seem to hit the system at its heart. It is unwise to downplay the issue of populism, but it is important to recognise that the turning point of globalisation in all major economies appears to have occurred well before the recent trade shocks. This is why the phenomenon of deglobalisation requires a much broader conceptualisation than the ‘backlash from globalisation’ or the ‘retreat from globalisation’ on which research is already well underway. Deglobalisation in the sense of reduced openness also occurs in countries where popular support for globalisation is still strong, and this is a research puzzle that has not yet been addressed.

Drivers of the turn towards deglobalisation

Phases of strong globalisation carry the seeds of their own destruction, that is, such phases generate the forces that ultimately set limits and force a retreat of internationalisation. A first mechanism operates in national economies: redistributing the gains from further openness to the people who lost from globalisation becomes more difficult at higher levels of globalisation. This is a double-edged sword. In the initial phase when a country starts to open up, the economy experiences steep increases in productivity and welfare, but once the low-hanging fruit has been picked the same increase in the intensity of globalisation brings less benefits to the economy. At the same time the costs of redistribution at a low intensity of globalisation are initially small, but they are on an increasingly steep path. This shift in the (marginal) costs and benefits of further globalisation shifts the political balance towards less openness

A second mechanism operates in the international arena. During both the Great Depression of the 1930s and the Great Recession, the leading economic power of the time deserted the rules of the game that underpinned globalisation and were actually designed by its initial interest in an open trade and investment climate. An open stable and relatively peaceful system, however, allows other countries to develop and grow faster, capturing a larger share of the benefits of globalisation. In the early phase of globalisation a smaller share from a larger economic pie may still be an improvement. At some point the costs of being a hegemon, however, outweigh the benefits. It is ironic, but sad, that the US and the UK (the hegemons that helped to build a constellation in which trade, democracy, and peace were reinforcing aspects of the world order) are opting against global and European governance.

Cease fire?

Deglobalisation is a structural transformation of the world economy. Political turbulence can perhaps hasten this process. To some observers, delays to the big topical trade shocks may therefore seem to help to turn the tide. Brexit and ‘Make America Great Again’ are, however, symptoms of underlying processes that have already generated significant trade and investment uncertainty and this is already exercising a concrete impact on trade and investment flows as firms and consumers are adjusting behaviour in anticipation of further trade shocks. The delay of the deadlines provides a pause at best. It is therefore pertinent to rethink global economic governance and make it resistant to deglobalisation. A repositioning of the extent of internationalisation is manageable, but then concerted action is necessary to make the required changes in the rules and regulations of the world economic system. Those rules and regulations should be redesigned to meet the requirements of globalisation and, as recent experiences have made crystal clear, also meet the challenges posed by a wave of deglobalisation.

References

Baldwin, R E (ed) (2009), The great trade collapse: Causes, consequences and prospects, a VoxEU.org eBook.

Davis, S J (2016), “An Index of Global Economic Policy Uncertainty,” Macroeconomic Review, October (updated on http://www.policyuncertainty.com).

Hoekman, B (ed) (2015), The global trade slowdown: A new normal, a VoxEU.org eBook.

Maddison, A (1995), Monitoring the World Economy 1820-1992, OECD.

Maddison, A (2001), The World Economy: A Millennial Perspective, OECD.

O’Rourke, K H (2018), “Economic history and contemporary challenges to globalization,” CEPR Discussion Paper 13377.

O’Rourke, K H (2019), “The end of globalization”, Vox Talks, 1 February.

Pástor, L and P Veronesi (2018), “Inequality Aversion, Populism, and the Backlash Against Globalization”, CEPR Discussion Paper 13107.

van Bergeijk, P A G (2018), “On the brink of deglobalization… again”, Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 11(1): 59-72.

van Bergeijk, P A G (2019), Deglobalization 2.0: Trade and openness during the Great Depression and the Great Recession, Edward Elgar.

Endnotes

The figure is intended to sketch a long-run perspective and thus by necessity focuses on merchandise trade in relation to world production. This of course ignores developments in services and financial flows.

To view the original piece, please click here.

Copyright © 2019 VoxEU. All rights reserved.