Given our collective failure to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions, the world will have to adapt to a certain level of climate change. This may mean that as climate change affects crops’ yield potential, new patterns of comparative advantage, and hence new trade flows, will emerge. This column examines the importance of the market adaptations in mediating welfare losses in the agricultural sector. The findings suggest a large role for international trade: when adjustments in trade flows are constrained, global welfare losses from climate change increase by 76%.

Curbing greenhouse gas emissions to mitigate climate change has proven to be a difficult objective, in large part because international coordination of the required mitigation efforts is very difficult. As a result, in a recent special report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) finds that limiting global warming to no more than 1.5°C (2.7°F) would require large reductions in emissions and important societal changes, although it remains within the realm of the possible (IPCC 2018).

Given the difficulty of achieving these changes and the fact that past emissions alone are likely to cause some warming over the coming decades, adaptation to climate change will be necessary. As noted by Anderson et al. (2018), an upside of adaptation is that it doesn’t rely on international coordination; individual countries, and even economic agents, can undertake adaptation, incentivised by environmental and price changes.

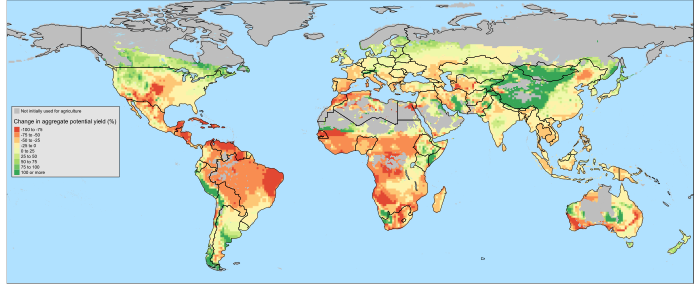

Agriculture is one of the sectors most impacted by climate change, but this impact may be very different between and within countries. Northern regions that currently have cold temperatures and short growing seasons may benefit from higher yields in some crops. Tropical regions, facing more extreme temperatures, may see reduced yields (see Figure 1 for the extent of regional variations).

Figure 1 Relative changes due to climate change in potential yields aggregated across crops

Note: Yields from the GAEZ project under scenario SRES A1FI.

But direct predictions from crop scientists do not equate to final welfare effects because several adaptation mechanisms may take place, mitigating damage. Some of these adaptation mechanisms have been studied extensively. For example, crop scientists have proved the adaptive role of changing varieties or planting times (Challinor et al. 2014). Economists have emphasised the role of within-country reallocation of land to crops or other uses more consistent with the yield under the new climate (Mendelsohn et al. 1994).

However, the role of market-mediated adaptation to climate change is still poorly understood. For example, market-mediated adaptation will come from the fact that landowners will change their land allocation not only because of the new potential yield but also because of changed prices under the new climate, which account themselves for all the adaptation in demand, supply, and trade.

In our recent study (Gouel and Laborde 2018), we analyse the potential role of market adaptations – both nationally and internationally – in reducing the economic cost of climate change in the agricultural sector. Because we model global agriculture using 11,801 fields, we are able to assess impacts on individual regions within countries as well as the resulting net changes in countries’ agricultural trade.

Our work provides insights on the role of market-mediated adaptation to climate change, with a focus on the adaptive role of international trade. To examine this question, we build a quantitative general equilibrium model of trade centred on agricultural products. This model builds on the modelling approach of Costinot et al. (2016) and represents the world using 50 regions (including many individual countries), 35 crops, one livestock sector, and one non-agricultural good. The model includes the following margins of adjustments, all separately parameterised to capture crop substitution within-field (11,801 fields in the model, represented at the 1-degree level), intensification of crop production, agricultural product substitution in food demand, crop substitution in livestock-feed demand, price elasticity of demand for the food bundle, and product substitution between country of origin. The model is calibrated to reproduce the market situation in 2011 as the baseline, using information about potential yield for each crop and each field under the current climate from the GAEZ project (IIASA/FAO 2012). To simulate the effect of climate change, we use the same source of information from crop scientists and change the crop potential yields to values under a climate change scenario.

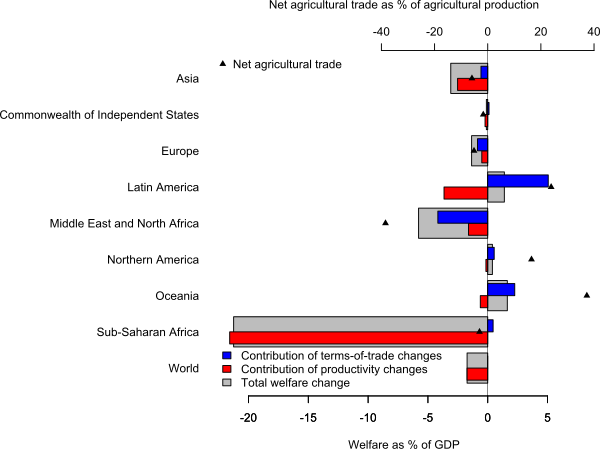

This simulated climate change shock delivers three main results about the adaptive role of trade. First, terms-of-trade changes heavily influence welfare effects. Figure 2 decomposes welfare changes into terms-of-trade changes and productivity changes, with the terms-of-trade changes summing to zero at the world level. All regions lose from reduced crop productivity (although a few individual countries may gain), but some are more than compensated by terms-of-trade gains. Because total food demand is inelastic, an average decrease in crop productivity will increase food prices substantially. So, net-food-exporting regions, namely Latin America, Northern America, and Oceania, will benefit, and the burden of adjustment to climate change will fall to net-food-importing regions, namely Asia, Europe, and the Middle East and North Africa.

Figure 2 Welfare decomposition of the effect of climate change on agriculture

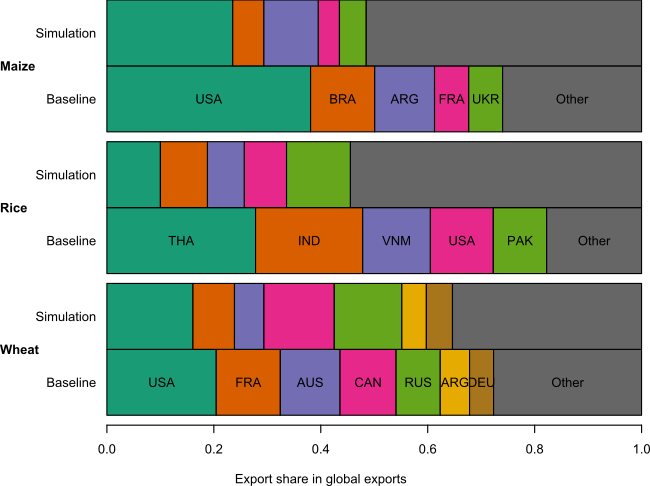

Second, future patterns of international trade flows in agricultural products may look extremely different from current patterns because of the effects of climate change. Figure 3 shows that simulated export shares of maize and rice bear little resemblance to their current market shares (baseline).

For the maize market, traditional exporters such as the US, Brazil, France, and Ukraine suffer large yield reductions and consequentially reduce their exports. Canada, Germany, and China, located in northern latitudes, have higher maize yields than at baseline. They step in to fill the gap, with the world production of maize even increasing by 19%.

The effects are similar for rice. The traditional rice exporters are tropical countries that are severely hit by climate change. Rice production moves north, and new exporters emerge, namely, China, Korea, and Japan. The export shares in the wheat market change less with decreases in some traditional exporters (Argentina, Australia, France, US) and increases in others, located in northern latitudes (Canada, Germany, Russia).

Figure 3 Changes due to climate change in the export shares of the major exporters

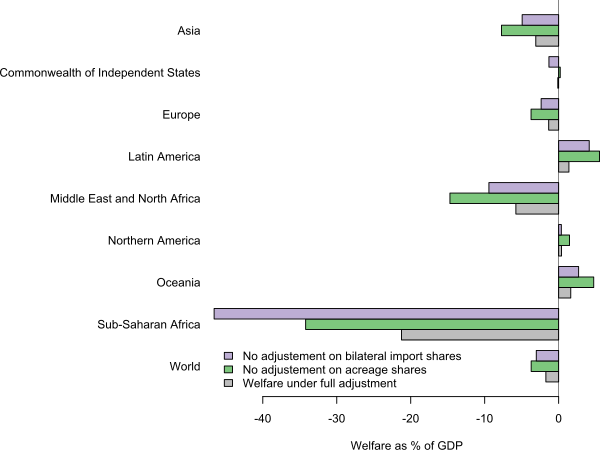

Third, crop choice and trade adjustment have important mitigating roles in climate change adaptation. To assess the welfare effects of market adaptation, we simulate the climate change shock while alternatively holding constant to their baseline values acreage shares and bilateral import shares. Figure 4 shows that these adaptation mechanisms play a large role, reducing global losses by 55% and 43%, respectively. So, change in crop choice appears to be the most important source of adaptation, but trade adjustments also play a key role.

Figure 4 Welfare results under full adjustment and limited adjustment

Conclusions

Despite large avoided losses allowed by changes in land allocation and in trade structure, many of the poorest countries are likely to bear a much larger share of the cost of climate change in agriculture than rich countries for a number of interacting reasons. As many poor countries are tropical, they are often the worst affected by climate change in terms of crop productivity. This direct effect is compounded by agriculture’s large share of the economic activity in these countries. Finally, in aggregate, poor countries tend to lose either from the terms-of-trade changes because they are net food importers (Asia, and the Middle East and North Africa) or from more limited adaptation through trade because of high trade costs and specialisation in crops with little trade (Sub-Saharan Africa).

Our results carry important policy recommendations, especially in terms of global policy and coordination. While the market adaptations analysed in this work depend naturally on the behaviour of private agents in a competitive market and thus seem much less prone to the coordination failure we are witnessing on greenhouse gas mitigation, they nevertheless rely significantly on an international trade system allowing very large reallocations of trade flows. Large terms-of-trade effects as predicted by our results may prompt uncooperative trade policies from policymakers to counteract these reallocations. If policies prevent trade adjustments as an avenue for adaptation, welfare losses would likely be worse in the long run.

In this context, some of the difficulties related to international coordination that we face for greenhouse gas mitigation may also plague adaptation. A rule-based trading system will be needed to enable climate change adaptation. Strengthening the role of the WTO should be viewed as integral to actively pursuing the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change agenda.

References

Anderson, S, T Anderson, A Hill, M Kahn, H Kunreuther, G Libecap, H Mantripragada, P Mérel, A Plantinga and VK Smith (2018), “The critical role of markets in climate change adaptation”, NBER Working Paper 24645.

Challinor, AJ, J Watson, DB Lobell, SM Howden, DR Smith and N Chhetri (2014), “A meta-analysis of crop yield under climate change and adaptation”, Nature Climate Change 4(4): 287–291.

Costinot, A, D Donaldson and CB Smith (2016), “Evolving comparative advantage and the impact of climate change in agricultural markets: Evidence from 1.7 million fields around the world”, Journal of Political Economy 124(1): 205–248.

Gouel, C, and D Laborde (2018), “The crucial role of international trade in adaptation to climate change”, NBER Working Paper 25221.

IIASA/FAO (2012), Global Agro-ecological Zones (GAEZ v3.0).

IPCC (2018), Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty.

Mendelsohn, R, WD Nordhaus and D Shaw (1994), “The impact of global warming on agriculture: A Ricardian analysis”, The American Economic Review 84(4): 753–771.

To view the original paper, click here.

Copyright © 2019 VoxEU. All rights reserved.