The Belt and Road Initiative, proposed by China in 2013, consists primarily of a series of infrastructure projects aimed at improving connectivity on a trans-continental scale. This column presents new evidence on the potential impact of the initiative on trade costs. It shows that through a reduction in shipment times, the initiative could substantially reduce trade costs for participating countries, with positive spillover effects on the rest of the world.

There is a lot of passion around the Belt and Road Initiative, but little economic research (Pomfret 2018, Ruta 2018). Some people are concerned about it, and the implications that building large infrastructure projects may have on environmental quality, on social standards for workers and displaced people, or on public debt of borrowing countries. Others focus on the opportunities from the Belt and Road Initiative that derive from the improved connectivity. For all, a key constraint is the lack of data to inform these debates. In our recent work (de Soyres et al. 2018), we use information on transportation projects, Geographic Information System (GIS) analysis, and sectoral estimates on the value of time to build a new database on shipment times and trade costs before and after the Belt and Road Initiative.

What is the Belt and Road Initiative?

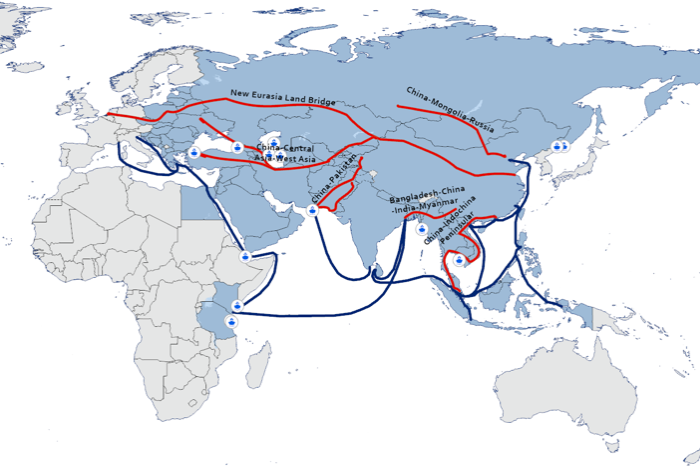

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), proposed by China in 2013, is an effort to improve connectivity and regional cooperation on a trans-continental scale. While the scope of the initiative is still evolving, the BRI consists primarily of the Silk Road Economic Belt (the ‘Belt’) and the New Maritime Silk Road (the ‘Road’) (Figure 1). The Belt links China to Central and South Asia and onward to Europe, while the Road links China to the nations of South East Asia, the Gulf Countries, East and North Africa, and on to Europe. Six economic corridors have been identified: (1) the China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor; (2) the New Eurasian Land Bridge; (3) the China–Central Asia–West Asia Economic Corridor; (4) the China–Indochina Peninsula Economic Corridor; (5) the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor; and (6) the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor.

Figure 1 The Belt and the Road

Whether the Belt and Road Initiative will succeed as a development strategy will largely depend on its impact on international trade and on integration more broadly. This, in turn, will result from the effect of the new and planned BRI transport infrastructure projects on shipment times and trade costs.

Estimating travel times and trade costs

In our paper, we make a first attempt to quantify how much the BRI will impact shipment times and trade costs. We do this in two steps.

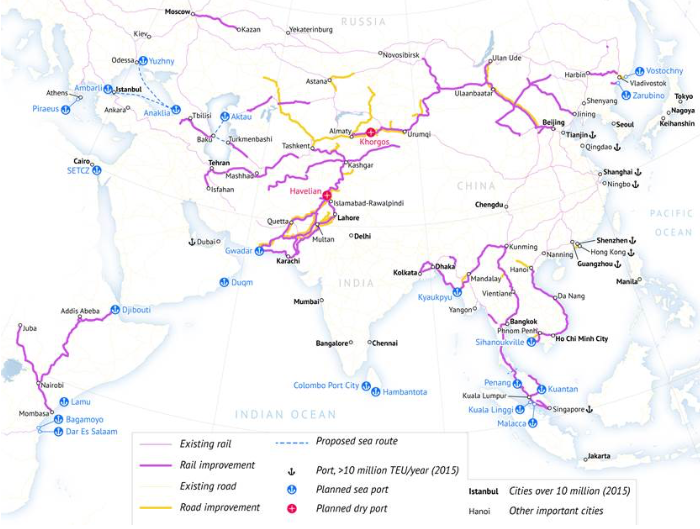

- First, we use a combination of geographical data and network algorithms to compute the reduction in travel times between 1,000 cities in 191 countries. As a starting point, we use the current network of railways and ports across the world and estimate the current shipment times between every pair of cities. From this reference point, we run an improved scenario where the transportation network is enriched with planned infrastructure projects that are linked to the Belt and Road Initiative (Figure 2). Comparing the pre and post-BRI scenarios allows us to quantify the changes in shipment times induced by the new and improved transport infrastructure projects.

Figure 2 BRI-related transport projects

- Second, we use sectoral estimates of the value of time from Hummels and Schaur (2013) to transform reductions in shipment time into reduction in trade costs. Different goods have different value of time – for instance, some goods such as fresh fruits are perishable and are very time sensitive; some inputs as microchips need to be delivered to producers just in time. As such, we need to compute the value of time for each pair of countries and each sector. These country pair-sector values of time can be further aggregated to quantify changes in trade costs by country.

Impact on travel times and trade costs

Using these methods, we produced new data on the impact of the Belt and Road Initiative on shipment times and trade costs. We find that:

- The Belt and Road Initiative will reduce shipment times for BRI economies, particularly along economic corridors.BRI economies experience a decrease in shipment times by 3.2% on average with the rest of the world, and by 4% with other BRI economies. The largest estimated gains are for the trade routes connecting East and South Asia and along the corridors that are part of the BRI. For instance, shipment times among countries in the China-Central Asia-West Asia economic corridor will decline by 12% due to the improved transport infrastructure.

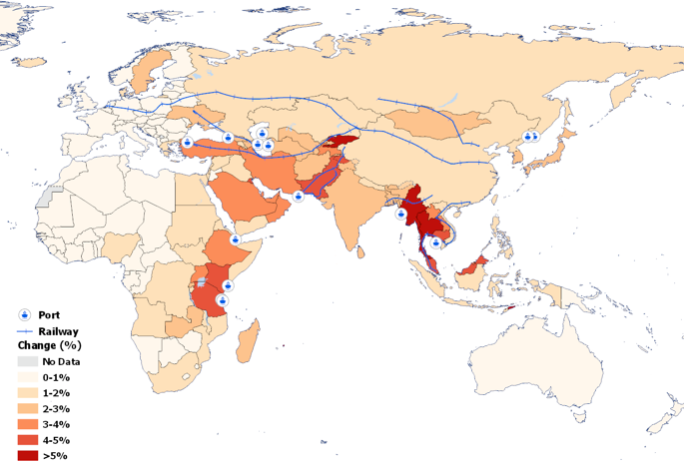

- Reduction in travel times translates into significant reductions in trade costs. Our analysis suggests that implementing all BRI transport infrastructure projects will reduce aggregate trade costs for the BRI economies by 2.8% on average with the rest of the world, and by 3.5% with other BRI economies. As for shipment times, the gains in trade costs vary widely across pairs of countries, with East Asia and Pacific as well as South Asia being the regions with the largest average reductions (Figure 3). Similarly, trade costs will fall more along the corridors.

Figure 3 Average decrease of trade costs per country

Note: For each country, all destinations are weighted by import flows.

- The Belt and Road Initiative could have positive spillovers on shipment times and trade costs of non-BRI economies. The average decrease in travel times and trade costs across all country pairs in the world is 2.5% and 2.2%, respectively. The reason for these effects is that non-BRI economies will benefit from the improved network of BRI infrastructure. For example, Tanzania’s Bagamoyo port is expected to benefit not only Tanzania but also several other countries in the region. As a result, when all BRI transportation projects are implemented, our analysis shows that shipment time between Australia and Rwanda is expected to decrease by 0.5%. Similarly, the improvement of Djibouti’s port will contribute to a 1.2% decrease in shipment time between Australia and Ethiopia.

The importance of complementary policy reforms

The focus so far has been on the impact of BRI-related transport infrastructure projects. But what if the Belt and Road Initiative could boost the efficiency of customs, reduce border delays, or improve management of economic corridors? As an extension of our main database, we present scenarios where those elements are explicitly taken into account.

We find that the implementation of complementary policy reforms magnifies the impact on shipment times and trade costs, especially along the corridors. For instance, if border delays were reduced by half, the reduction of shipment times along corridors would range from 7.7% for the China-Indochina Peninsula Economic Corridor to 25.5% for the China-Central Asia-West Asia Economic Corridor. Similarly, trade costs would fall by 5.6% for the China-Indochina Peninsula Economic Corridor and by 21.6% for the China-Central Asia-West Asia Economic Corridor. These large effects are not surprising given the importance of trade facilitation bottlenecks between BRI economies (Bartley Johns et al. 2018).

Conclusion

This is a first look at the economic effects of the Belt and Road Initiative and more research is needed. The main contribution of our work is in the new methodology used to quantify changes in trade costs due to transportation projects and the novel data that provide detailed information on BRI-induced changes in shipment times and trade costs for the world and for BRI economies. These data will help researchers interested in better understanding the impact of the Belt and Road Initiative on a number of economic variables, including growth, trade, foreign investment, or the spatial distribution of economic activity. The data may also be useful to investigate the systemic effects of BRI projects on non-economic variables such as air pollution or biodiversity or on social outcomes, such as the changes in poverty for certain groups in specific geographic locations.

Editor’s note: The views expressed in column are those of the authors and they do not necessarily represent the views of the World Bank Group.

References

Bartley Johns, M, C Kerswell, J L Clarke and G McLinden (2018), “Trade Facilitation Challenges and Reform Priorities for Maximizing the Impact of the Belt and Road Initiative”, MTI discussion paper No. 4, World Bank.

De Soyres, F, A Mulabdic, S Murray, N Rocha and M Ruta (2018), “How Much Will the Belt and Road Initiative Reduce Trade Costs?”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper no. WPS 8614.

Hummels, D and G Schaur (2013), “Time as a Trade Barrier”, American Economic Review 103(7): 2935-59.

Pomfret, R (2018), “The Eurasian Landbridge and China’s Belt and Road Initiative”, VoxEU.org, 2 May.

Ruta, M (2018), “Three opportunities and three risks of the Belt and Road Initiative”, VoxEU.org, 18 June.

To view the original posting of this article on VoxEU.org, click here.

Copyright © 2018 VoxEU.org. All Rights Reserved.