Background

Investment plays a large and growing role in U.S.-China commercial ties. For many years, the Chinese government invested much of its foreign exchange reserves in U.S. assets, particularly U.S. Treasury securities. These reserves stemmed from China’s large annual trade surpluses, foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows, efforts to halt or slow the appreciation of its currency, and policies that restrict capital

outflows. More recently, however, the Chinese government has sought to diversify its investments by encouraging its firms—many of them state-owned enterprises (SOEs)—to invest overseas, become more globally competitive, and gain access to raw materials and cutting-edge technology.

As a result, China’s outward FDI stock globally has risen significantly, from $34.7 billion (0.5% of world total) in 2001 to $1.9 trillion (6.3% of world total) in 2018. (The United States accounts for $6.5 trillion, or 20.9%, of global outward FDI stock, down from 31.8% in 2001.)

While a significant share of Chinese investment in the United States is in U.S. public and private securities, U.S. capital flowing into China largely has taken the form of FDI. (This is due, in part, to Chinese restrictions on portfolio investment.) Initially, after China began opening up its economy in 1979, most U.S. FDI in China was channeled to the export-oriented manufacturing sector, so as to take advantage of China’s ample supply of workers and their comparatively low wages. As China’s economy began to grow rapidly, its booming domestic market has attracted a growing share of U.S. (and global) FDI.

China’s Holdings of U.S. Securities

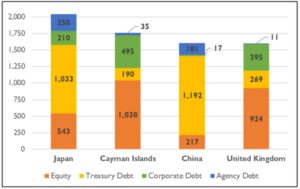

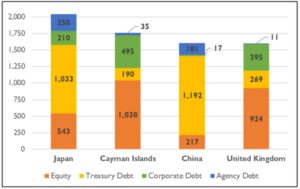

U.S. financial securities consist of securities issued by the U.S. government and private sector entities. They include Treasury securities, government agency securities, corporate securities, equities (e.g., stocks), and other debt. As of June 2018 (the most recent period for which complete data are available), China’s investment in U.S. securities totaled $1.6 trillion, up $66.2 billion (4.3%) from June 2017 levels, making China the third-largest holder after Japan and the Cayman Islands (Figure 1). China’s share of total foreign holdings of U.S. securities stood at 8.3% (down from its all-time high share of 15.2% in 2009).

U.S. Treasury securities are the largest category of U.S. securities and one of the main vehicles through which the government finances budget deficits. As of June 2019, approximately three-fourths (or $1.11 trillion) of China’s total U.S. public and private holdings are Treasury securities, which are generally considered by investors as “safe-haven” assets. Chinese ownership of these securities has decreased in recent years from its peak of $1.31 trillion in 2011. Nevertheless, they remain significantly higher than in 2002, both in dollar terms (up over $1 trillion) and as a percent of total foreign holdings (from 8.5% to 17.0%). (In June 2019, Japan overtook China to become the largest foreign holder of Treasury securities.)

Figure 1. Foreign Holdings of U.S. Securities in 2018 (in billions of U.S. dollars)

Source: CRS with data from the U.S. Department of the Treasury.

Notes: Long and short-term U.S. securities at the end of June 2018.

Concerns About Chinese Holdings

Some analysts and Members of Congress have raised concerns that China’s large holdings of U.S. securities could give it leverage over U.S. foreign and economic policy issues. They argue, for example, that China could seek (or threaten) to liquidate a large share of its U.S. assets or significantly cut back its purchases of new securities over a policy dispute. Others contend that these holdings give China little practical leverage. Attempts to harm the U.S. economy by unloading these holdings would likely cause comparable harm to the Chinese economy. Such attempts could also cause the U.S. dollar to depreciate sharply against global currencies, reducing the value of China’s remaining U.S. dollar assets. In 2012, the U.S. Department of Defense concluded that China’s use of Treasury securities as a coercive tool is not a credible threat, and even if carried out, the effect would be limited and cause more harm to China than to the United States.

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)

In 2018, the United States and China were each other’s largest trading partners. Yet, the level of bilateral FDI has remained relatively low. Amid trade tensions, a U.S. vetting regime with a newly broadened scope for reviewing certain foreign investments for national security implications, and tighter Chinese regulations on capital outflows, Chinese FDI in the United States has slowed since 2016.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), net U.S. FDI flows to China in 2018 were $7.6 billion (down 22.9% from 2017). Net Chinese FDI flows into the United States were negative (-$754 million, compared to $25.4 billion in 2016), as outflows exceeded inflows (e.g., asset divestitures). Additionally, the stock of U.S. FDI in China was $116.5 billion (up 8.3% from 2017), while Chinese FDI in the United States was $60.2 billion (up 3.7%), on an ultimate beneficiary ownership basis (Figure 2). (In 2018, China accounted for 1.4% of total FDI stock in the United States, up from 0.05% in 2002.)

Figure 2. Chinese FDI Stock in the United States (in billions of current U.S. dollars)

Source: CRS with data from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

BEA also collects financial data of U.S. multinational enterprises (MNEs) investing abroad. Data for 2016 (the most recent year for which data are available) indicate that sales by foreign affiliates of U.S. firms in China totaled $463.5 billion (down 4.3% from 2015). China was the third-largest market for U.S.-affiliated firms overseas, after the United Kingdom ($676.7 billion) and Canada ($604.2 billion). In addition, U.S. affiliates in China employed 2.1 million workers, paid $35.3 billion in employment compensation, and spent $3.5 billion on research and development (R&D).

U.S. Residential Real Estate

In its 2019 survey (April 2018–March 2019), the National Association of Realtors (NAR) found that over the past seven years, Chinese investors have been the largest foreign buyers of U.S. residential real estate. (NAR statistics on China include buyers from mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.) During 2018-2019, Chinese investors purchased 19,900 properties valued at $13.4 billion. While these purchases had risen sharply, from $7 billion in 2011 to $31.7 billion in 2017, their dollar value in 2019 was down 55.6% ($17.0 billion) from 2018.

Alternative Measurements of Bilateral FDI

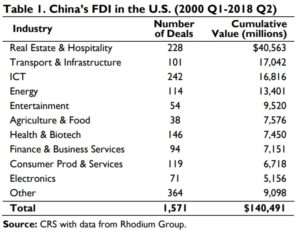

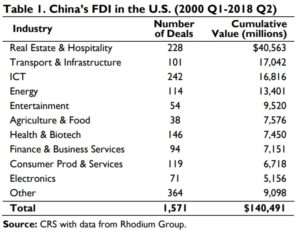

Some analysts contend that BEA’s data and Chinese official government sourced data do not accurately reflect the value of China’s FDI in the United States. Rhodium Group (RG), a private consulting firm, notes that BEA “counts FDI coming directly from China and omits flows which are routed through third countries, a practice used extensively by Chinese firms due to capital controls and inadequate legal and financial infrastructure at home.” RG developed its own dataset to track investment by Chinese-owned firms using commercial databases and news reports. Using its tracker, it puts gross Chinese FDI flows to the United States in 2018 at $5.4 billion and gross U.S. FDI flows to China at $13.0 billion. In addition, it estimates cumulative Chinese FDI in the United States at $140.5 billion and U.S. FDI in China at $269.6 billion (Table 1).

Chinese Restrictions on FDI

Although China is one of the world’s top recipients of FDI, the Chinese government imposes numerous restrictions on the level and types of FDI allowed in China. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)’s 2018 FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index, which measures statutory restrictions on FDI in 69 countries, ranked China’s FDI regime as the sixth most restrictive. Recent surveys by U.S. and European business groups suggest that foreign firms in China may be less optimistic about the Chinese market than in the past, due in part to perceived growing protectionism and current U.S.- China trade tensions. Liberalizing China’s FDI regime, U.S. officials argue, would boost U.S. business opportunities in—and U.S. exports to—China.

Concerns About Chinese FDI in the United States

While some U.S. businesses and governments at various levels have been actively seeking Chinese investors, Chinese FDI in the United States has come under increasing scrutiny by policymakers. Some Members have expressed concerns over investments by government-backed entities that appear to target industries and technologies that the Chinese government has identified as critical to China’s future economic development. Concerns over the ability of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) to review adequately the national security aspects of FDI in the U.S. economy led to the enactment of the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA) in August 2018. The Act seeks to modernize CFIUS and expand the types of investment subject to review, including certain non-controlling investments in “critical technology.”

Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT) Negotiations

In 2008, the U.S. and China launched negotiations for a BIT, an agreement that typically contains provisions to provide reciprocal investment protections and encourage bilateral commercial ties. In 2013, China agreed to negotiate a “high standard” BIT with the U.S., which would include opening new sectors to FDI and generally not discriminating against U.S. firms invested in China. The two sides were unable to reach an agreement by the end of the Obama Administration, and the Trump Administration has not resumed the talks. Many analysts contend that a BIT could significantly boost bilateral FDI and trade flows.

Note: Sections of this In Focus rely on work originally written by

Wayne M. Morrison, former CRS Specialist.

To read original report, click here

CRS US China Investment Ties